It was the middle of April 2021, the second wave of the pandemic had just about begun to rear its ugly head in India. I was looking forward to spending quiet time with my new-born and celebrating a decade of living with and loving my partner. Then everyone got CoVid (by everyone I mean everyone including my then 2 month old) and all hell broke loose. I remember the horror it became, the frantic search for medicines, the desperation for a hospital bed, leaving the city in disgust and then the three months of deaths, deaths and more deaths.

On the 20th of July, in a mass insult to folks like me and indeed the average Indian, the Central government informed the Rajya Sabha that absolutely no deaths due to lack of oxygen were specifically reported by states and UTs during the second CoVid-19 wave, recently it went on record denying the existence of a panel it had earlier claimed to have constituted to investigate oxygen shortages. This same government runs a ‘CORONA HELPDESK’ broadcast channel on telegram. Telegram is my messenger platform of choice but the government – as you know – has a presence everywhere. I’m a loyal follower of the Corona Helpdesk on telegram because it is such a steady source of incorrect information and provides me oodles of content for the data literacy course (shamelss plug coming up) I teach online.

In this article I am going to help you, dear reader, examine public claims of success at beating back the pandemic, as made by the current Modi government, with a view to expose the systematic data obfuscation undertaken to create these claims. However before I get into that I want to spend some time on why this trend – of over information and largely wrong information – is not just the result of the 'communication age' we live in or accidental but instead is a rather old, tried, tested and wildly successful tactic used by fascist governments the world over.

Information Warfare

To begin with, the term ‘data obfuscation’ is not a term I made up and that I am glibly attributing to this government or fascist governments in general. Those of us who work in data science know, for instance, that data obfuscation – otherwise known as data masking procedures – serves a real purpose in data-led work and that purpose is ‘testing’. Data obfuscation is the process of replacing sensitive information with data that looks like real production information, making it useless to malicious actors. It is primarily used in computer development environments – developers and testers need realistic data to build and test software, but they do not need to see the real data. The same principle applies to making a dataset with missing information more complete. Ironically, the purpose of data obfuscation is to protect from ‘malicious intent’.

However, in practice, data obfuscation is not just this legitimate purpose or replacement of data. It is instead, the systematic use and reporting of data and cherry-picked numbers used to wilfully spread incorrect information as well as distract from the real message that a chart or a number intends to communicate.

Data obfuscation is now a quietly and powerfully wielded weapon in information warfare and makes real and rapid contributions to the state of disinformation we all now live in. In the book, Visualising Fascism (Thomas, 2020), the author recounts many examples through history of propaganda that increasingly relied on covert obfuscation – one such prominent example is of Japan in the 1940s viz.

‘In 1940, the year leading up to the government’s consolidation of domestic photography magazines, a dispute (ronsō) broke out among the ranks of Japanese photographers concerning their duty to the state. At issue was the relation between art as a craft and politics as an imperative. Was it possible to serve both? On the one hand, Ina Nobuo (1898–1978), long a leading critic in the Japanese photography world, argued quite subtly that a photographer could be true both to his craft and to the nation. Serving the regime was not, he said, a matter of merely “communicating” (iu) the right subject matter but a matter of “leading” (michibiku) intellectually, emotionally, and sensually. To lead in this way required a self-aware practice that was cognizant of both method and message, technique and topic. Personal talent and patriotism were not at odds. In making this point, Ina insisted that “the difference between journalism (hōdōsei) and art (geijutsu) is a non-issue.” A honed aesthetic was a necessary component of good reportage (hōdōshashin); elevating the nation required a purposive art (mokuteki geijutsu).’

Data obfuscation is a kind of propaganda, similar to what Adolf Hitler felt in 1924, data ‘is a truly terrible weapon in the hands of an expert’. During the two decades that followed the terrible twenties, Nazi leaders showed the world bold, new ways to use propaganda, thus laying the old and now solid foundations of data obfuscation. Through a variety of sophisticated techniques, the Nazi Party successfully swayed millions of Germans and other Europeans with appealing ideas of a utopian world and perpetuated genocide.

Indeed several fascist states such as Salazarist Portugal and Fascist Italy shared characteristics in their approach to propaganda and data obfuscation. Like Modi’s India, all three were civilian and not military dictatorships, headed by charismatic leaders who drew on a revolutionary rhetoric and placed ideology at the core of the construction of their idea of a new state. This is the New State we are all going to become occupants of if we do not rise to defeat it, this state is not intended to be ‘neutral’ and actively works to extend control over all forms of organised social activity. The aim of these regimes –characterized by an undisputed leadership, a single ideology and a conflict-avoiding institutional structure is the totalitarian occupancy of the state.

If one examines history in very broad strokes (of over centuries), one can see that fascist forces in the nineteenth century experienced social upheaval characterised by liberal revolutions and the secularisation of the state and urbanisation/modernisation. Alongside came what can only be called the ‘massification’ of society, including the development of education and the mass media, which both enabled the construction of a single new narrative and the emergence of parties, and institutions of mass socialisation, such as trade unions, factories and war trenches.

Throughout the post-Second World War period, authoritarian regimes tried to subvert public opinion, and regimes with totalitarian tendencies and made the distinction between education and propaganda slowly disappear. History makes it clear that goal of propaganda was (and is today too) to create a reality in which all the pieces fit together seamlessly, with no contradictions or any possibility of testing the veracity of the official ideology.

Massification works to reinforce capitalism. Repression and propaganda constitute the two most important instruments of this effort and they work together to ensure the functioning of a dictatorship and industrial cartels. Violence has not always been the principal means for regime consolidation in this context.

Indeed, propaganda and its emphasis on ideology is the new ‘war’ of the post-Second World War world that seeks to change the hearts and minds of citizens through the deployment of simple and powerful ideological messages. In the India of Modi’s dreams, ‘data-driven technologies’ – as he himself has stated on many an occasion – is at the centre of ideological messaging. Patriotism and nationalism must also be evidence-backed, no matter that these are as manufactured as consent is.

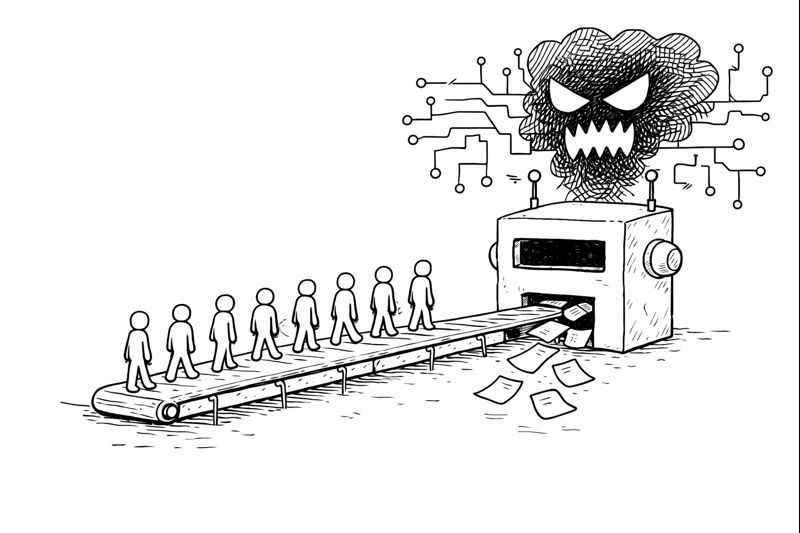

Data obfuscation is useful for a regime, no matter what type of propaganda goal it has, viz. active consensus, passive consensus or dissensus. Active consensus refers to the active participation of the citizenry rather than simple acceptance, thus we have massive troll armies in Modi’s India. It is not a goal but a means to achieve concrete objectives that would otherwise not be achievable. Passive consensus, by contrast, or the mere management of dissensus is often enough to ensure regime survival. One really easy way to do this is by persuading people that there is no alternative to the regime, so it is best not to oppose it – the claim that the opposition leader is an idiot is not in fact a fact at all but instead a carefully constructed narrative.

Propaganda aims to fully engage a population with regime structures, to mobilise it so as to obtain active consensus. This is a qualitatively different idea from the concept of public opinion and that of the public arena. Rather than a meeting-place between state and civil society, in a society such as ours at this time point, this arena is entirely occupied by the state or, in this case, a party.

The central aim is to contain the masses within the life of the state. To fulfil this goal, propaganda has to simplify concepts so as to make them readily digestible and easily memorised and one of the easiest ways to do this is through data which appears non-political or factual and indisputable. This kind of propaganda also has to be repetitive, partial, and seemingly beyond question; in other words, it has to convey only ‘absolute truths’. Such propaganda can only exist in contexts of low or non-existent competition and contestability.

So what does this have to do with CoVid?

It is now widely acknowledged that the Modi government has been incompetent in its handling of the CoVid pandemic. Not only was the first lockdown (in April 2020) implemented badly with no prior notice, it also caused mass migration and loss of lives. In the year that followed, the Modi government failed to ramp-up medical facilities despite this being placed on record in parliament and then catastrophically failed to arrange enough oxygen, regulate super spreader events and even prioritised vaccine diplomacy versus vaccination atma-nirbharta when it mattered!

Despite this – criticism of the Modi government’s handling of Covid within India is low. One of the reasons this is so is because of the narrative of success in battling the pandemic, which the Modi government has successfully built. The narrative is a careful attempt to manufacture consent around the idea that this government has done all it could to deal with CoVid, and is of course untrue. Central to this narrative and all the fancy graphics on the Covid Helpdesk Telegram channel, for instance, is data obfuscation – using data incorrectly to build support for a misleading conclusion. The remainder of this article is dedicated to debunking some of these untruths.

What Could Have Been Done

Poor policy design and implementation has been the hallmark of this government and most of its policies have had far-reaching consequences for the poor. India’s economy has always been skewed. It has been primarily agrarian and then it leapfrogged to the services sector (at least in urban and peri-urban areas) which has been hit badly by a series of India’s worst economic decisions of all times – demonetisation and GST. The infrastructure to support a services sector boom such as a robust education system at foundational level or basic healthcare, is non-existent. The pandemic has taken a toll on tourism and low-level IT jobs too. Construction is in the doldrums.

Years of underinvestment in agriculture, social-security, healthcare and education (features of capitalism which prioritise profit of the few over all else) has set up the economy for failure which died a natural death when demonetisation, GST and then CoVid hit. Could the pandemic have been managed better? When one looks at some of the decisions made by the Modi government, one can tell that relatively better management could indeed have been possible.

India's top virologist recently quit a scientific advisory panel after criticising the government’s ‘stubborn resistance to evidence-based policymaking’, an opinion that rings true. Modi’s mismanagement has included huge political rallies for a string of elections and mass religious gatherings that went ahead, including the Kumbh Mela with millions of mostly maskless folk. The second wave of the pandemic arrived, because in the year intervening between the first hasty lock-down that left hundreds upon hundreds of migrant workers without food and shelter and this one, the government did next to nothing to prepare for another wave of infections.

Indeed so bad was the policy planning that oxygen supplies were not ramped up and field hospitals hastily assembled together after the first wave were actually actively dismantled.

Recording and Reporting CoVid Deaths

At the centre of understanding CoVid deaths in India is the issue of how CoVid deaths are recorded and reported. Story after story in the press, records that India has vastly underreported deaths from CoVid 19, especially in the second wave but also in the first wave, largely because of instructions and pressure from the very top to officially record cause of death as a co-morbidity and not CoVid per se.

The last time public health saw something like this happen was when AIDS was discovered in India. The two stories have much in common. Like HIV, the coronavirus causes fatalities in bodies with weakened immunity – this places vulnerable people such as the aged with other diseases as the most likely targets. Someone with cancer, for instance, or hypertension, is much more likely to die of cancer or a heart attack if they have CoVid.

Part of the trouble is that there is far too much variation in how States count deaths. To begin with, in India, every State and Union Territory does it differently. Then there is the issue of matters of birth, marriage and death being religious and therefore unrecorded – in India only one in every five deaths is actually medically certified. There is no law that requires medical certification of cause of death. According to the World Health Organization, a death should be recorded as Covid-19-related if the disease is assumed to have caused or contributed to it, even if the person had a pre-existing medical condition, such as cancer, but of course, the Modi government has scant respect for the WHO.

It is now widely known that private and public hospitals have been under tremendous pressure to misreport and fraudulently classify CoVid deaths as something else, easily done when there has been a complicated medical history. This is one kind of data obfuscation and this is not the first time the Modi government has tried to obfuscate data – in a very public scandal in 2019, for instance, Modi’s government tried to suppress data showing a rise in the unemployment rate.

Undercounting of CoVid deaths is something of a global phenomenon too, in India it has certainly been a concern for a long while. There are several reasons why undercounting could be an issue; what separates unintentional undercounting resulting from data complications from data fabrication as done by the Modi government is intent. Undercounting can happen because testing capacity varies markedly across countries and within countries over time, which means that the reported CoVid-19 deaths as a proportion of all deaths due to CoVid-19 can also vary markedly across countries and within countries over time.

Demography also complicates this issue – for instance countries with an aging population (as a proportion of the total population) will likely see more deaths from COVID-19 in older individuals, especially in long-term care facilities, and these go unrecorded because many such people are already sick anyway. This is exactly what happened with Ecuador, Peru and the Russian Federation for instance. It is worthwhile asking why do excess deaths matter anyway? Estimating an accurate COVID-19 death rate is important both for modelling transmission dynamics of CoVid 19 and to make better forecasts!

So how does one tell how many people actually died as a result of the Modi government’s catastrophe? The agreed method is to estimate State-wise how many excess deaths have occurred when compared to average deaths in the civil births and deaths register, i.e. excess deaths are typically defined as the difference between the observed numbers of deaths in specific time periods and expected numbers of deaths in the same time periods. But this is hardly a straightforward exercise. If you think about it there are at least six aspects which influence how excess deaths can be measured:

The proportionality of COVID-19 deaths when related to COVID-19 infections

An increase in deaths caused due to needed health care being delayed or deferred during the pandemic

An increase in deaths due to increases in mental health disorders including depression, increased alcohol use and increased opioid use

A reduction in overall deaths due to decreases in injuries because of general reductions in mobility associated with social distancing mandates

Reductions in deaths due to reduced transmission of other viruses

Reductions in mortality due to chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease and chronic respiratory disease, that occur when frail individuals who would have died from these conditions died earlier from COVID-19 instead

To correctly estimate excess CoVid-19 mortality[1], one would need to take into account at least these six determinants of change in death numbers since the onset of the pandemic. Now this is a data-issue, a logical question to ask therefore is, where does India stand Unsurprisingly India’s excess deaths data is not even in the public domain – therefore one cannot even try to make better or more accurate estimates. For example, I was able to obtain detailed excess deaths estimates for a variety of countries on a public tracker with zero information and data from India:

Making data unavailable is the first way to obfuscate data, because then, researchers have to rely on all sorts of estimates.

The disastrous truth of the lack of any official numbers about the pandemic is that since the onset of CoVid, statistics regarding its progression, has been largely dependent on a voluntary collective that keeps https://www.covid19india.org up and alive. This collective, a ragtag group of unpaid volunteers led this effort with their hearts and provided painstakingly collected data using self-funded data architecture for nearly a year. They are now closing shop due to lack of time and money as they note in their blog here. As for now anyone's best bet on data on the pandemic is the dashboard from the Development Data Lab which relies on estimatation procedures, some robust some not so much but all defnitely guesswork.

Read that again, there is no official government-led data effort on CoVid. Wow.

On 31st July 2021, for instance, the website IndiaSpend reported that health data from the National Health Mission website run by Government of India pertaining to the pandemic year – which demonstrated a sudden spike in deaths particularly in rural India – suddenly went offline due to ‘server problems’. The disappearance was timed to stave off the sudden and welcome mushrooming of papers estimating India’s excess deaths accurately using this data.

Devastatingly, the data recorded an estimated 1.5 million children also missed essential vaccines (such as the BCG) during the same period. Curiously, data pertaining to health issues OTHER than CoVid during the same period and much older periods remained online. Perhaps a computer CoVid virus decided to infect MOHFW servers, who knows?

What is a Covid Recovery

India has made a big deal of CoVid recoveries and recovery percentages in all official communication regarding CoVid. Unfortunately, recovery rates and the number of recovered cases is a lousy indicator of how a country has dealt with any epidemic or pandemic. Consider this, while the pandemic has been devastating, it is still less than fatal and even mild for several million people in India. All these people, who do not die, ultimately recover making high recovery rates kind of pointless. Diagnosis usually has only two outcomes – either a person recovers or dies. So when there is a rise in the pandemic there is also a rise in the number of cases recovered, aka no new information.

Over 50% of the population in India is 18-35, we are a young country and young folk typically have better immunity i.e. the odds of recovery and healing are naturally high and that is a matter of demography and luck for the Modi government. That someone is a bright learner says nothing really about the teaching ability of an instructor.

Nearly all prior pandemics show that recovery rates remain high and vary in-tandem with a pandemic’s own timeline. It is possible entirely that India might reach a 99% recovery rate but that does nothing to signal an end to the pandemic. Despite the uselessness of this statistic, the Modi government has plastered poster after poster and media campaign after media campaign with pointless heat maps of recoveries by region in green – a colour known to psychologically signal ‘all-is-well(ness)’ to the mind.

A similarly useless statistic is the positivity percentage which is also being used widely by the Modi government, particularly against States without a BJP government – as we can see in the case of Kerala which is continuously under attack for a high number of CoVid cases. What is a positivity rate? A high percentage of positive cases means that more testing should probably be done – and it suggests that it is not a good time to relax restrictions aimed at reducing coronavirus transmission. Because a high percentage of positive tests suggests high coronavirus infection rates (due to high transmission in the community), a high percent positive can indicate it may be a good time to add restrictions to slow the spread of disease. A high positivity rate, because it is a ‘rate’ is a proportion i.e. it is the numerator while the denominator is the all-important context. In this case, a positivity rate is a function of the total number of tests conducted. Therefore, a low positivity rate also reflects low testing and high positivity reflects a higher proportion of population being tested.

One can recall in the case of HIV this same fallacy played out. While it continues to be true that the southern states of India have high HIV numbers, the naming and shaming of AP and TN for high AIDS rates in the country has been unfair. It has only been recently acknowledged in public health discourse, that the southern states of India have also tested much more efficiently than other states ever did – with mandatory testing of women from HRGs and community testing. Therefore, suggesting that States like UP or MP are doing better than Kerala on positivity rates or caseload without using “testing” percentages as context is basically an incomplete story.

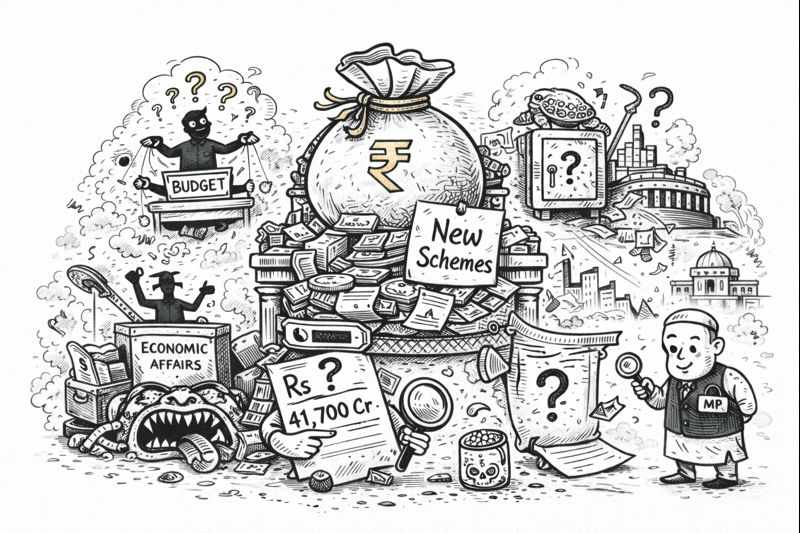

Examples of dubious infographics:

Despite this, Modi propaganda includes heat maps on positivity percentage as a vital part of its strategy this time in red because the ‘danger’ is declining.

Yet another statistic used almost always without context is ‘doubling time’. Doubling time is a term conveniently borrowed from the world of finance. Now, doubling time refers to the time it takes to double the number of active cases and as such, it has to be calculated, based on the emergence of new cases and changes every day and as such doesn’t mean anything when monitored every day. A much better method is to simply calculate moving averages. It is also an unreliable measure because it is impacted by a variety of external factors such as wide differences at the State and even district level, given population characteristics, low or high testing or contact tracing, or because of human migrations which could be seasonally driven or driven by labour markets or those imposed by bad policy.

Where from Vaccine and Witherto?

In another startling piece of data obfuscation, the Modi government continues to report India’s vaccination drive as one of the most successful anywhere in the world. Vaccination experiences have been terrible for even those of us who can afford to pay – for many of the poor the irony of being illiterate and needing CoWin registration even if done on the spot is too visible to ignore. Vaccine availability State-wise has also been questionable with Bengal having a whopping (projected) 66% shortfall of vaccine availability, the best States have approximately a quarter of their populations projected to suffer from vaccine shortfall.

Between January and May 2021, India bought roughly 350 million doses of the two approved vaccines - the Oxford-AstraZeneca jab, manufactured as Covishield by the Serum Institute of India (SII), and Covaxin by Indian firm Bharat Biotech. The vaccines were cheap at procurement (but pricy for those who needed to take the vaccines) and sufficient for barely 20% of the population. During the same time, PM Modi took to the television no less than three times to declare that India had defeated Covid. Then came ‘vaccine diplomacy’, exporting more vaccines than were administered in India by March and then mass pyres.

While India continues to celebrate vaccination success with absolute numbers (India has surpassed the number of vaccines administered by the US for instance), in reality it has vaccinated only four per cent of its population while this is at nearly fifty per cent for the US, India’s favourite country for comparisons. While PM Modi likes to emphasise that it is currently vaccinating around four million people every day, what he chooses not to say is that it should be administering double that number if we want to beat the pandemic this year. The government data that mysteriously vanished earlier included data that shows that 14% less women are getting vaccinated than men, especially in rural areas.

The day India rolled out free (but not really free, it still costs money in private hospitals and government hospitals have queues and no vaccines very often) vaccinations to everyone aged 18+, PM Modi’s heart was gladdened, given the record turnout of 8.5 million doses, but then probably sank as this was followed by a sharp decline with average daily inoculation falling below 3 million. Madhya Pradesh, which recorded 1.7 million vaccinations on Monday (vaccine rollout day), saw only 68,370 doses administered till 10pm on Tuesday – a drop of 96% between the two days. In Haryana, there was a 75% drop in daily vaccination numbers on Tuesday (128,979 doses administered till 10pm), compared to 511,882 Monday. Guess which party runs these States?

India’s CoVid vaccination programme is a colossal failure and it is important to do a better job because there are real lives at stake. Does how much and how fast we vaccinate make a difference? Absolutely. All over the world Covid’s base rate fallacy is making headlines, in India the government reports this absolutely wrong statistic with impunity every day.

Let us try and understand what the base rate fallacy is with an example of how GOI reports out percentage of hospitalisations. Say we have a good efficacious vaccine in supply – without this vaccine 9 out of 10 people get hospitalised (90%) and with it only 1 out of 10 (1%) get hospitalised. Now suppose, 90 out of 100 people get vaccinated, what share of the hospitalised are vaccinated? What is the share if this is 50 out of 100 people?

When 90 per cent are vaccinated we find that 9 vaccinated people are hospitalised and 9 unvaccinated people are hospitalised i.e. 50% of the hospitalised are vaccinated but there are only 18 hospitalisations in absolute numbers. Contrast this with what happens when there is a lower vaccinated proportion of population when 50 per cent people are vaccinated we end up with 5 vaccinated people being hospitalised, 45 unvaccinated people being hospitalised and 10% of the hospital admitted being vaccinated overall, but with 50 hospitalisations in absolute numbers.

Thus, not only does vaccination save lives it also reduces the burden on a rapidly-overwhelmed public health system. Therefore the corollary is also true – a failed vaccination programme is a public health and policy disaster.

Does Prediction Make Good Policy?

How did the Modi government make such a mess? Modi’s decisions are the result of his fascination with poor policy advice received from the now widely publicised Menon model of Ashoka fame. This is not the first time we know PM Modi to have been taken with bad ideas that have cost lives – demonetisation had a similar story behind it.

We now know that compartmentalised models of CoVid spread are largely unreliable. Not only do we not have enough knowledge of potential factors that need to be factored into models, we also lack procedure. While the now famous professor Menon has given many interviews and unarguably influenced government policy, his own interviews state that they he believes virus mutations are a random event (not conditioned by lock-down or social distancing methods) – a position which is scientifically incorrect.

Menon’s model was entirely untested (nobody ever checked if it reflected the accurate state of affairs), used sparse input data and was never open to public scrutiny. The model was not only poor science, the fact that it was taken seriously by government was also poor policy. I venture that it was not accidental. Professor Menon has since gone on record to state that India’s vaccinations aren’t halting the pandemic in contrast to his earlier predictions. Perhaps he too lost someone to CoVid?

The truth is that policy shouldn’t be based on models, using evidence in policy-making is desirable, but only inasmuch as it can help save lives.

Ultimately, the Modi government’s CoVid strategy has centred on data obfuscation – making concentrated efforts to mask the failure of routine health services, attacking State federalism and using data sets as a political tool.

These are all powerful weapons in the hands of an openly hostile, anti-people fascist government. For such governments, reliable data and truth in data collection and reporting is fundamentally antithetical to capitalist interests.

Modi’s government has developed expertise in data obfuscation, featuring techniques of dramatic storytelling, gaslighting and metric manipulation in tandem with amplification of false facts, the diffusion of post-truth and the logic of numbers.

India’s Covid numbers badly need public scrutiny and analysis. The data needs public ownership, for policy is for the public and should also be determined by the public when you have a fascist at the helm of affairs.

PS: A version of this article will be published elsewhere online

[1] See; https://ourworldindata.org/covid-excess-mortality?country= for an excellent primer on this issue.

Write a comment ...