On how a decade of academic persecution, public university destruction, and systematic defunding has set the stage for legislation that will complete the transformation of education from a public good to private extraction—while raising a generation unprepared for citizenship.

My son is twelve. He attends a reasonably good school in Delhi, the kind that charges enough to make you wince but not enough to be elite. He learns things—facts, formulas, test-taking strategies. What he increasingly doesn't learn is how to think. How to question. How to be the kind of engaged citizen a democracy requires.

This isn't entirely the school's fault. They're responding to incentives—board exam results, competitive entrance rankings, parental anxiety about placements. The system rewards compliance and memorisation; it punishes curiosity and critique. And the upcoming Viksit Bharat Shiksha Adhishthan (VBSA) Bill will cement this architecture into law.

But before we examine what this legislation will do, we need to understand what has already been done. The VBSA Bill doesn't arrive in a vacuum. It arrives after a decade of systematic destruction of public higher education, persecution of critical academics, defunding of universities, and regulatory capture by ideological interests. The legislation is the capstone, not the foundation. The foundation was laid in faculty terminations, arrested professors, silenced researchers, and institutions too frightened to host controversial ideas.

The Persecution of Ideas

Let me name some names, because the pattern requires specificity.

Hany Babu, Associate Professor of English at Delhi University, was arrested in July 2020 in the Bhima Koregaon case. He spent over two years in jail, contracted a severe eye infection that went untreated for months, and lost vision in one eye. His crime, as best as anyone can establish, was participating in caste annihilation conferences and writing about Dalit literature. The NIA has produced no credible evidence linking him to violence. He remains on trial.

Sabyasachi Das, an economist at Ashoka University, resigned in September 2023 after the university faced pressure over his research. His paper analysed electoral patterns suggesting manipulation in favour of the ruling party—statistical work, published in a peer-reviewed journal. The university issued a confusing disavowal that satisfied no one, least of all the faculty who signed a statement of concern.

Pratap Bhanu Mehta, one of India's most respected public intellectuals, resigned from Ashoka in March 2021. He later stated that his position had become "untenable" because his public writings were a "political embarrassment" to the university's funders. Arvind Subramanian, former Chief Economic Adviser, resigned in solidarity the next day.

The TISS crisis of 2024: Over 100 faculty members at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences—India's premier institution for social work education—were terminated or faced non-renewal of contracts in a single stroke. Many had been teaching for years on "project-funded" positions, a category that allowed TISS to avoid permanent hiring while extracting permanent labour. When central funding dried up, these teachers were simply disposed of. The crisis revealed how completely India's public universities have been hollowed out from within.

Delhi University's ad-hoc crisis: Over 4,500 teachers at DU work as "ad-hoc" or "guest" faculty—employed semester to semester, year to year, sometimes for a decade or more without permanent appointment. They receive a fraction of UGC pay scales, have no job security, and can be terminated without cause. The Delhi University Teachers' Association (DUTA) has documented cases of teachers working for fifteen years without regularisation. When permanent positions are eventually advertised, the age limit often disqualifies the very teachers who have been doing the job.

This is not a series of unfortunate incidents. This is policy.

The Great Defunding

The persecution of individual academics occurs against a backdrop of systematic financial starvation. Consider the numbers:

India allocates 2.9% of GDP to education, against the 6% recommended by every Education Commission since Kothari (1966) and promised in every policy document, including NEP 2020. The gap between 2.9% and 6% represents approximately ₹10 lakh crore annually that should be going to Education but isn't.

Higher Education receives 0.64% of GDP—among the lowest rates for any major economy. China spends 1.5%; Brazil and South Africa exceed 1%; even countries at similar income levels to India invest more.

The UGC budget for 2024-25 shows that the higher education allocation is growing more slowly than inflation—a real-terms cut. Meanwhile, the government proudly announces new IITs and central universities, expanding the denominator while shrinking the numerator. The inevitable result: each institution receives less.

Faculty vacancies across central universities exceed 40%. At IITs and IIMs—the institutions that receive the most attention and relatively the most funding—vacancy rates still hover around 20-30%. The message is clear: we will build buildings and announce schemes, but we will not hire the people needed to make them work.

This creates a self-fulfilling prophecy. Underfunded public universities cannot compete for talent. Students who can afford alternatives flee to private institutions. The flight of paying students further undermines public university finances. And legislators point to declining enrolments as evidence that public investment is wasted.

What the VBSA Bill Actually Does

Into this landscape of persecution and defunding comes the Viksit Bharat Shiksha Adhishthan Bill, 2025—introduced in Lok Sabha on December 15, 2025 and immediately referred to a Joint Parliamentary Committee amid opposition walkouts.

The Bill's text runs to 78 pages. Let me explain what they contain.

Regulatory centralisation: The VBSA Bill abolishes the University Grants Commission (UGC), the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE), and the National Council for Teacher Education (NCTE)—the three bodies that have governed Indian higher education since the 1950s. In their place comes a single apex body: the Viksit Bharat Shiksha Adhishthan, a 12-member Commission in which states get exactly one rotating seat, each with a one-year term.

The Emergency's 42nd Constitutional Amendment moved Education from the State List to the Concurrent List in 1976—itself a controversial centralisation born of authoritarian impulse. But concurrent jurisdiction at least meant shared authority. The VBSA Bill operationalises central supremacy: where state regulations conflict with Commission standards, Commission standards prevail.

The funding-regulation merger: NEP 2020 recommended separating academic regulation from funding decisions through distinct bodies—the Higher Education Grants Council (HEGC) for financing and the National Higher Education Regulatory Council (NHERC) for standards. This separation matters: it creates institutional buffers between the political executive and academic governance. A government that controls both can starve institutions that displease it while rewarding those that comply.

The VBSA Bill ignores this architecture entirely. The unified Commission controls accreditation, standard-setting, curriculum frameworks, and funding recommendations—all of which are appointed by and answerable to the central Ministry.

Language and curriculum control: The three-language formula has been contentious since anti-Hindi agitations in Tamil Nadu in 1965 left 70 people dead and forced the Centre to retreat from mandatory Hindi instruction. The VBSA Bill revives this battle.

Under the Bill's framework, central bodies will determine "essential competencies" that may include specific language requirements. Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.K. Stalin has explicitly opposed what he calls a "backdoor Hindi imposition". Karnataka, Kerala, and West Bengal have raised similar concerns. The Bill's proponents insist that no language is being mandated; its critics note that "flexibility" in the hands of the central authorities becomes coercion for states lacking political leverage.

The Bill That Wasn't—And the Ghost Legislation

Before proceeding, a clarification on what doesn't exist.

No legislation called the "Bharatiya Shiksha Bill" or "Rashtriya Shiksha Aayog Bill" has been introduced in Parliament. These terms circulate in media speculation, but you won't find them in parliamentary records. The National Education Policy 2020 promised a Rashtriya Shiksha Aayog—an apex body chaired by the Prime Minister that would cover all Education from pre-school to postgraduate. Five years later, it remains unlegislated.

What we have instead is narrower and, in some ways, more dangerous. The VBSA Bill covers only higher Education. School Education reforms continue through executive orders and scheme modifications—the path of least parliamentary resistance. When the government wants legislative imprimatur, it reaches for higher Education; when it wants to avoid scrutiny, it governs schools by fiat.

This is a pattern. Announce grand transformation. Deliver selective implementation. Avoid the mechanisms—parliamentary debate, state consultation, committee examination—that might impose accountability.

The Learning Crisis No One Wants to Name

While we argue about governance structures, Indian children are not learning.

The ASER 2024 report documents the catastrophe with careful precision. Among rural children aged 14-18:

25% cannot read a Class 2 level text in their own language—basic sentences that a seven-year-old should manage

57% cannot solve a simple division problem (three digits divided by one digit)

Only 5.6% of enrolled students could demonstrate foundational literacy and numeracy appropriate to their grade

This is not a post-pandemic anomaly. Learning outcomes have been stagnant for a decade. COVID-19 deepened the crisis, but it predates COVID-19. Multiple ASER surveys, the National Achievement Survey, and international assessments all tell the same story: Indian schooling produces credentials without competence.

The VBSA Bill does not address this. It cannot address this. The Bill reorganises higher Education governance, while the foundations of that system—the schools that feed it students—remain broken.

Consider what this means for democracy. A population that cannot read beyond basic sentences cannot engage with policy documents, follow complex arguments, or evaluate competing claims. They can, however, be manipulated by emotional appeals, religious mobilisation, and strongman rhetoric. The learning crisis is not a bug in India's current political system; it is a feature.

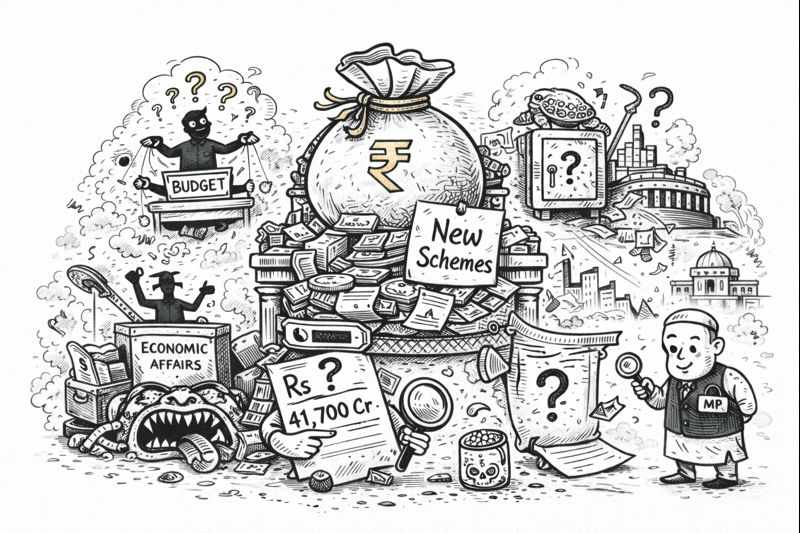

The Economics of Educational Extraction

Follow the money, and the logic of the VBSA Bill becomes clear.

Indian families spent ₹8.33 lakh crore on education in 2023-24—over 10% of household consumption expenditure. This figure has risen faster than incomes, meaning Education consumes an increasing share of family budgets while delivering decreasing returns.

The coaching industry alone captures over ₹58,000 crore annually—not because parents want to enrich their children's learning, but because formal schooling fails so comprehensively at preparing students for competitive exams that a parallel private system has emerged to fill the gap.

Every year, over 13 lakh students migrate to Kota and other coaching hubs. Some die there—over 100 suicides between 2019 and 2024 in Kota alone. This is a wealth transfer from families to the Education industry, enabled by public school failure.

The VBSA Bill accelerates this transfer. NEP 2020 advocates treating public and private institutions "on the same criteria, benchmarks, and processes"—language that sounds like fairness but functions as deregulation. It promotes "light-touch regulation" and an "outcomes-based approach" with "suitable flexibility" on infrastructure norms.

Fee regulation is conspicuously absent. NEP 2020 states families must be "protected from unreasonable increases in tuition fees," but never operationalises this protection. Foreign universities entering India under the 2023 UGC regulations can set their own fee structures with no caps. Seven have received Letters of Intent: Southampton, Liverpool, York, Aberdeen, Western Australia, Illinois Institute of Technology, and Instituto Europeo Di Design.

These institutions serve a specific market segment. They are not building hostels in Bhagalpur or recruiting first-generation learners from Bundelkhand. They cater to families who can pay international fees in a domestic setting—a sliver of India's student population, but a lucrative one.

The Reservation That Doesn't Appear

The word "reservation" does not appear anywhere in the 66-page NEP 2020 document. Not once.

CPI(M) General Secretary Sitaram Yechury raised this in a letter to the Prime Minister. Then-Education Minister Ramesh Pokhriyal clarified that NEP "affirms the constitutional mandate of reservation enshrined in Article 15 and Article 16." But constitutional mandate is one thing; policy architecture is another.

The shift toward private provision has direct implications for social justice. Private universities are not required to implement reservations. Foreign universities entering India face no affirmative action requirements. As the private share of enrollment grows—and as policy frameworks favour that growth—the institutions where SC/ST/OBC students have constitutional access shrink in relative terms.

The enrollment data reveals existing disparities. In central universities, SC students constitute 14.2% of enrollment, compared with a 15% population share. In state universities, representation varies wildly by state politics. In private universities—the fastest-growing sector—data is sparse, but available evidence suggests SC/ST representation falls well below population proportions.

This is structural exclusion without explicit policy. No one has to announce the end of the reservation. You simply build a system where reservation doesn't apply, watch public institutions decay, and let market forces do the rest.

The Federal Dimension

The VBSA Bill is best understood as part of a broader centralisation project that extends far beyond Education.

I have written before about fiscal federalism—how cesses and surcharges exclude states from revenue they would otherwise share, how GST has transferred effective taxation power to the Centre, how southern states like Karnataka now receive just 15 paise of every rupee they contribute to central taxes.

The Education Bill follows the same logic. States currently run their own universities, set their own curricula, and hire their own faculty. They have constitutional responsibility for Education under the Concurrent List. The VBSA Bill does not remove this constitutional provision—that would require amendment—but it operationalises central supremacy through regulatory architecture.

Tamil Nadu cannot refuse Commission accreditation standards, even if those standards embed Hindi requirements. Bihar cannot maintain hiring practices that differ from Commission norms. Kerala cannot protect faculty whose research embarrasses the central government. The states become implementation arms for centrally determined policy.

For a country as diverse as India—22 scheduled languages, hundreds more spoken, distinct literary traditions, regional histories, and local pedagogical practices—this is not administrative efficiency. It is cultural homogenisation by regulatory design.

The Citizenship That Won't Be Taught

My son came home last month with a civics assignment: explain the concurrent list. Education, I told him, is shared between Delhi and the states. The Centre can make policy, but Tamil Nadu decides which language you learn. West Bengal can run its own curriculum. Kerala can refuse to teach what it considers propaganda.

I was describing a constitutional arrangement that may not survive his school years.

The irony is profound. We are dismantling federal Education governance while failing to teach students what federalism means. We are persecuting academics who study democracy while claiming to build a "developed India."

We are producing graduates who can pass exams but cannot evaluate a political claim, who have credentials but not competencies, who know answers but cannot ask questions.

The VBSA Bill arrives at a moment when Indian Education requires expanded public investment, strengthened access for marginalised communities, and preserved federalism respecting linguistic and cultural diversity. The legislation's trajectory—concentrating power in New Delhi, enabling private expansion without equity safeguards, and weakening institutional buffers between political executive and academic governance—suggests priorities oriented in the opposite direction.

The Joint Parliamentary Committee examination offers an opportunity for substantive revision, though whether that opportunity will be seized remains uncertain as the bill moves toward what could be the most consequential Education legislation since 1956.

My son asked what happens after the explanation of the concurrent list. I told him he should learn to ask better questions—questions about power, about who decides, about why this curriculum and not that one.

What I cannot tell him is whether asking such questions will be permitted by the time he reaches university.

This article relies on primary sources, including PRS Legislative Research's Bill tracking, parliamentary proceedings, UDISE+ data, ASER reports, UGC statistics, and state government statements. Earlier coverage sometimes referenced legislation that does not exist in parliamentary records—the "Bharatiya Shiksha Bill" or "Rashtriya Shiksha Aayog Bill." This article addresses the actual legislation introduced in December 2025.

Further reading:

Write a comment ...