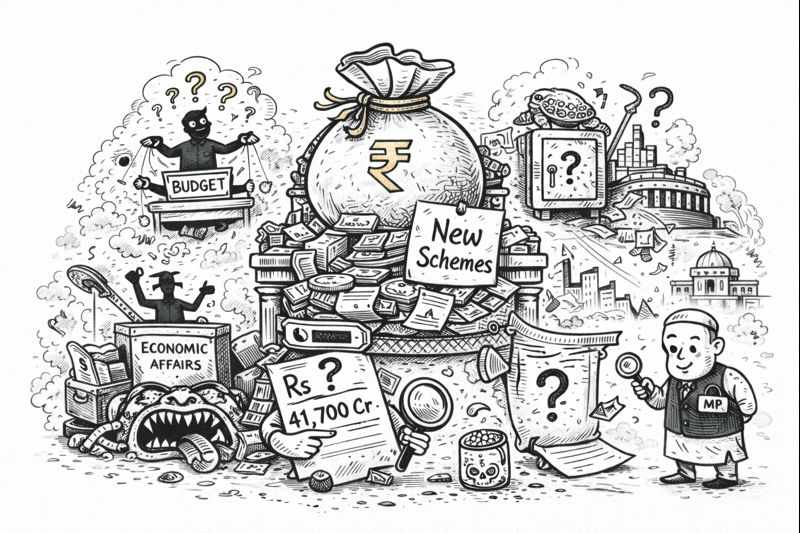

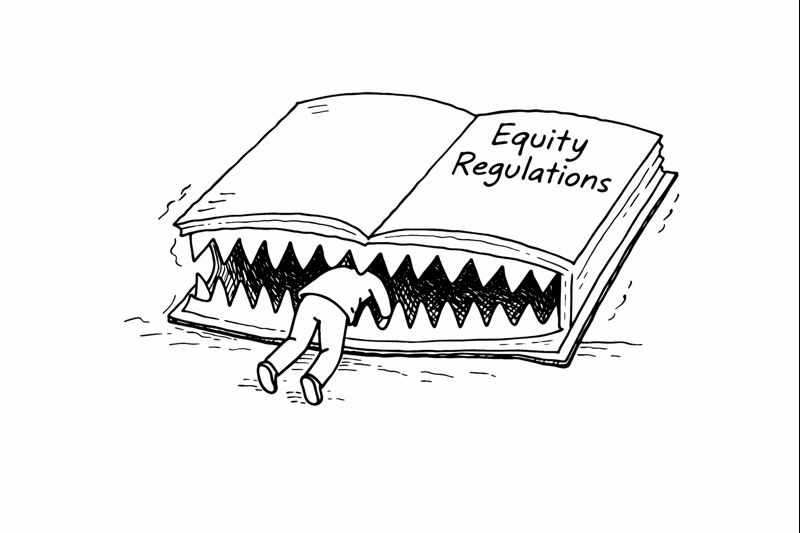

How the Department of Economic Affairs allocated Rs 62,593 crore to undefined "New Schemes," spent only 14.5%, faces zero parliamentary scrutiny, and what this reveals about fiscal governance designed for opacity over outcomes.

Three days before the Union Budget 2025-26, while analysing the Economic Survey's critiques of state "fiscal populism," I kept returning to a single line in last year's budget documents. The Department of Economic Affairs had allocated Rs 62,593 crore to something called "New Schemes" - with no details available. By the revised estimates, only Rs 9,068 crore had been spent. That is Rs 53,525 crore that simply disappeared between announcement and implementation, with no parliamentary questions asked, no CAG audit conducted, and no public explanation of what these "schemes" actually were.

This year, the same department has allocated Rs 41,700 crore to the same undefined line item. The pattern deserves scrutiny not because it represents corruption or misappropriation but because it exposes something more systematic: a fiscal governance architecture where opacity serves institutional interests, where accountability mechanisms fail to ask obvious questions, and where the gap between budget announcements and development outcomes remains deliberately unmeasured.

What we know about "New Schemes"

The terminology is misleading. "New Schemes" was introduced for the first time in the Interim Budget 2024-25 presented in February 2024. There is no historical budget series to track. The allocation appeared suddenly, consumed 78-84% of the Department of Economic Affairs' total departmental budget, and then vanished in execution.

The numbers across two budget cycles:

2024-25 (Interim Budget): Rs 70,449 crore allocated

2024-25 (Full Budget): Rs 62,593 crore allocated, Rs 9,068 crore spent (14.5% utilization)

2025-26: Rs 41,700 crore allocated

PRS Legislative Research, in their analysis of all three budgets, has flagged this allocation with identical wording: "details not available." No budget document, expenditure profile, or demand for grants discloses which schemes comprise this allocation, what their objectives are, where implementation is occurring, or who the intended beneficiaries might be.

The entire sum is classified as capital expenditure, accounting for 6.8-7.5% of India's total capital outlay. It represents roughly what the central government spends on MGNREGS or PM-KISAN combined - except that those schemes have names, objectives, beneficiaries, and implementation mechanisms subject to audit and parliamentary oversight.

The organizational mismatch

The Department of Economic Affairs is not an implementing agency. Its 14 functional divisions handle economic policy formulation, currency and coinage, financial markets oversight, bilateral and multilateral cooperation, and budget preparation. Its associated bodies include the Finance Commission (a constitutional body under Article 280), the Financial Stability and Development Council, and the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board.

None of these functions requires direct capital investment in implementation schemes. DEA prepares the Union Budget but does not execute development programs. It advises on economic policy but does not build infrastructure. The placement of Rs 41,700-70,449 crore in "scheme" allocations within DEA represents a fundamental mismatch between organisational mandate and budgetary allocation.

This suggests three possibilities: it is a placeholder for unannounced projects, a contingency fund avoiding supplementary budget approval requirements, or a fiscal management tool that creates apparent spending capacity while achieving deficit targets through non-implementation.

The accountability vacuum

I searched parliamentary question databases in both the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha. There are no questions addressing what schemes comprise this allocation, why utilisation collapsed to 14.5%, or what happened to the Rs 53,525 crore that remained unspent in 2024-25.

The Standing Committee on Finance examines the DEA's Demand for Grants annually. While the Estimates Committee noted in 2021 that "savings occurred in 99-100 departments" between 2017 and 2020, no specific scrutiny of the "New Schemes" allocation exists in publicly available committee reports.

The Comptroller and Auditor General's reports on Union Government Finance Accounts address general unspent balance issues but do not examine "New Schemes" specifically. This represents a governance anomaly: Rs 175,000 crore in allocations across two budget cycles, with no public disclosure of purpose, no parliamentary questioning of utilisation, and no audit examination.

Is this pattern unique?

The evidence says no. The 2024-25 budget reveals underspending as structural rather than exceptional:

* Jal Jeevan Mission: Rs 70,163 crore allocated, revised to Rs 22,694 crore (68% reduction)

* Ministry of Jal Shakti (total): Rs 98,714 crore allocated, revised to Rs 51,558 crore (48% reduction)

* Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana: Approximately Rs 1,36,000 crore allocated, revised to Rs 76,000 crore (44% reduction)

* Centrally Sponsored Schemes (total): Rs 5,05,978 crore allocated, revised to Rs 4,15,356 crore (18% reduction)

This is not an administrative failure. It is a design feature. When budget estimates systematically exceed revised estimates across ministries, and when fiscal deficit is calculated using actual expenditure rather than budgeted estimates, inflated allocations that remain unspent mechanically improve deficit arithmetic.

The fiscal deficit for 2024-25 compressed from 4.9% of GDP (Budget Estimate) to 4.8% (Revised Estimate) partly through this mechanism. Governments can announce ambitious spending programs while meeting deficit targets through non-implementation, creating perverse incentives in which underspending becomes fiscally advantageous.

The fiscal centralisation connection

The "New Schemes" opacity exists within a broader architecture of fiscal discretion. Under Article 270 as amended by the 80th Constitutional Amendment (2000), cesses and surcharges are excluded from the divisible pool shared with states. The scale has grown substantially:

2011-12: 10.4% of Gross Tax Revenue

2020-21: 20.2% (pandemic peak)

2024-25: Approximately 23% projected

The CAG has documented Rs 3.69 lakh crore in cess collections not transferred to designated purposes. The Oil Industry Development Board collected Rs 2.95 lakh crore since 1974 but transferred only Rs 902 crore (0.3%). The Health and Education Cess collected Rs 52,732 crore in 2021-22, but only Rs 31,788 crore (60%) was transferred. The GST Compensation Cess retained Rs 47,272 crore in the Consolidated Fund of India between 2017-19 for purposes other than compensating states.

CAG observed these amounts were "retained in the Consolidated Fund of India and was available for use for purposes other than for which it was levied." Whether "New Schemes" represents another mechanism for such parking cannot be determined without transparency about its actual composition.

What states lose

The 15th Finance Commission recommended 41% of the divisible pool be transferred to states. The Centre is projected to share approximately 32% of central taxes with states during FY 2024-25 - a 9 percentage point gap representing tens of thousands of crores annually.

At the 2024 Finance Ministers Conclave, states documented systematic erosion. Kerala's share of tax devolution dropped from 3.88% to 1.92%. Tamil Nadu's share fell from 7.931% (9th Finance Commission) to 4.079% (15th Finance Commission). Kerala's Finance Minister characterised the shift as "cooperative federalism" becoming "coercive federalism."

The 15th Finance Commission itself noted that "the divisible pool as a percentage of the gross revenues of the Union has been consistently falling." D.K. Srivastava, Chief Policy Advisor at EY India, observed: "There is no effective increase in the share of tax revenues transferred to the states."

This connects to the Economic Survey's critique of state "fiscal populism" through unconditional cash transfers. The Survey estimates aggregate spending on such programs could reach Rs 1.7 lakh crore in FY26 and warns of fiscal unsustainability. What it does not mention is that states implement these schemes partly because constitutional transfers have shrunk through cess mechanisms, GST compensation defaults, and delayed devolution - forcing states to compete for voter support with the fiscal tools remaining to them.

Budget credibility as a governance failure

India's fiscal transparency ranking from the International Budget Partnership stands at 46-48 out of 100. The public participation score is 19/100 versus a global average of 25. Budget oversight by the legislature scores 39/100.

The IMF's 2020 Working Paper "Enhancing Fiscal Transparency and Reporting in India" stated: "Current fiscal transparency and reporting practices in India place it behind most peer G20 economies, implying that policy makers are lacking critical data to ground their fiscal and other economic planning decisions."

Transparency International India noted in 2018 that "Bangladesh has better transparency than India in its system" - a comparison that should concern a nation positioning itself as a global economic leader.

What needs to change

The "New Schemes" allocation exposes institutional weaknesses requiring systematic reform rather than incremental adjustment.

Parliamentary oversight: The Standing Committee on Finance should require the disclosure of scheme composition, objectives, and implementation timelines prior to allocation approval. Quarterly tracking of budget-versus-actuals with ministry-level disaggregation should be published and scrutinised. The Estimates Committee's 2021 observation about savings in 99-100 departments should trigger investigative rather than descriptive analysis.

Fiscal architecture: The 16th Finance Commission should address the widening gap between recommended and actual devolution by establishing mechanisms to verify the actual transfer of collected cesses to designated purposes. Cesses and surcharges should be time-bound and subject to mandatory parliamentary review. The constitutional distinction between divisible and non-divisible pools should be revisited to prevent systematic erosion of state revenues through technical mechanisms.

Budget methodology: Moving from cash-based to accrual accounting would expose commitments that remain unfunded. Establishing an independent fiscal council (as recommended by NIPFP scholars) would create accountability structures aligned with execution rather than announcement. Making revised estimates subject to parliamentary approval rather than executive discretion would force governments to defend underspending explicitly.

Immediate transparency: The Department of Economic Affairs should be required to disclose the composition of the Rs 41,700 crore "New Schemes" allocation in Budget 2025-26. If schemes are genuinely in the formulation stage, provisional objectives and implementation timelines should be presented. If this represents contingency planning, that should be stated explicitly rather than hidden in vague terminology.

The larger question

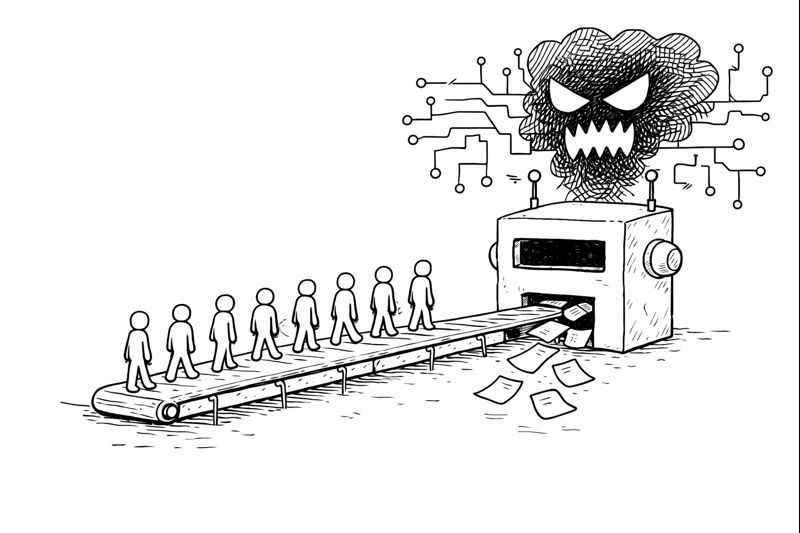

The Rs 53,525 crore that disappeared between the Budget Estimate and the Revised Estimate in 2024-25 represents not only unspent funds but also unexercised accountability. When allocations worth hundreds of thousands of crores can be announced without names, underspent without parliamentary questions, and rolled over without audit scrutiny, the budget ceases to be a governance document and becomes a communications tool.

The Economic Survey critiques states for fiscal populism while the central government perfects fiscal opacity. It warns that unconditional cash transfers undermine economic stability, while diverting Rs 3.69 lakh crore in cess collections to purposes other than those stated. It emphasises the need for outcome-linked support systems, yet presides over a budget architecture in which outcomes remain systematically unmeasured.

The problem is not that governments announce ambitious programs. The problem is that the announcement has become disconnected from implementation; fiscal deficit targets are achieved through non-spending rather than through efficiency; and the constitutional architecture of revenue-sharing is being systematically undermined by technical mechanisms designed to avoid explicit policy debate.

Until "New Schemes" is required to explain what it actually means, until Rs 41,700 crore requires more justification than two words in a budget document, and until accountability mechanisms ask the obvious questions about where allocated funds actually go, India's fiscal governance will remain structured around opacity rather than outcomes.

The question is not just what happened to Rs 53,525 crore in 2024-25. The question is what kind of democracy accepts that we will never know.

Varna is a development economist and writes at policygrounds.press.

Further Reading

Interim Union Budget 2024-25 Analysis, PRS Legislative Research

Enhancing Fiscal Transparency and Reporting in India, IMF Working Paper, 2020

Indian budget less transparent: Anti-corruption watchdog, Business Standard, 2018

Shrinking of States' share in divisible pool, Shankar IAS Parliament

Share of Cesses & Surcharges in Gross Tax Revenue Falls to 14.5% in 2023-24, FACTLY

Over Rs 3,69 Lakh Crores Collected as Cess Not Transferred to Relevant Fund: CAG, Revoi

Centre violated GST Compensation Cess Act, used funds allocated for states elsewhere: CAG report, Scroll.in

Rise in cess, surcharge shrinking states' share in pool of taxes: Kerala CM, Business Standard, 2024

Recent Budgetary Reforms for Better Management of Government Expenditure, PRS Committee Reports

Budget 2026 to incorporate recommendations of 16th Finance Commission, Business Standard, 2026

Write a comment ...