India's top 1% now holds more wealth than during the British Raj. The government's response—Jan Dhan accounts, PM-KISAN transfers, DBT efficiency—smooths consumption flows while leaving the stock of wealth untouched. Meanwhile, Scotland is attempting something India refuses to consider: legislating wealth redistribution. This essay examines why.

I have been a working development economist for over twenty years now. I have a PhD. I have worked for international development organisations, for the government, and for research institutions. And yet, when I look at my own income trajectory over this period—adjusted for inflation, measured against the cost of housing in the cities where I have lived, calculated as a share of what my male colleagues with similar qualifications earn—I find it difficult to claim that I have experienced meaningful wealth accumulation. I own no property that I have purchased with my own income. I have modest savings. My financial security depends entirely on continued employment in a sector that offers few permanent positions to women who take breaks to have children.

I mention this not to complain but to make a point about how we think about economic progress. When I co-authored the Oxfam India Inequality Report in 2022, the data we compiled indicated that India's billionaires doubled their wealth during a pandemic that pushed 230 million people into poverty. The report generated headlines, parliamentary questions, and some indignation. But I noticed that the public discussion focused almost entirely on the very rich and the very poor—the extremes. What rarely gets discussed is the vast middle: professionals, small business owners, salaried workers, people like me who work steadily for decades and find that the gap between our economic position and genuine financial security never quite closes.

This essay is about that gap, and about the distinction that explains it: the difference between flows and stocks. Income is a flow—it arrives, is spent, and is replenished. Wealth is a stock—accumulated assets that generate returns, provide security against shocks, and transfer across generations. India's welfare state has become remarkably good at smoothing consumption flows for the poor. What it refuses to do is alter the distribution of wealth stocks. Understanding why requires examining both what India does and what it deliberately chooses not to do—and comparing it to places that have made different choices.

The Billionaire Raj: What a Century of Data Shows

The economists who have documented India's wealth concentration most rigorously are Nitin Kumar Bharti, Lucas Chancel, Thomas Piketty, and Anmol Somanchi. Their 2024 World Inequality Lab study is remarkable for its temporal scope—it tracks inequality from 1922 to 2023, a full century of data assembled from tax records, national accounts, and household surveys. The title they chose, "The Rise of the Billionaire Raj," is not polemic. It is a precise description of what the numbers show.

India's top 1% now holds 40.1% of national wealth—the highest concentration since tracking began under British colonial rule. To grasp what this means in human terms: the bottom 50% of Indians—roughly 700 million adults—share 6.4% of national wealth among themselves. Half the country holds less wealth collectively than the richest 10 million Indians hold individually. The top 1% income share reached 22.6% in 2022-23, higher than during the colonial period, higher than contemporary South Africa, Brazil, or the United States.

The trajectory matters as much as the current position. Billionaire wealth has grown from under 1% of national income in 1991 to 25% by 2022. India went from one dollar billionaire at the time of liberalisation to 162 today. This is not the natural consequence of economic growth—the comparison with China demolishes that argument. Both countries began their reform eras at similar levels of inequality. China has stabilised its top 1% income share at roughly 16% since 2006. India's continued climbing to 22.6%—50% higher despite significantly lower GDP growth. The divergence reflects policy choices, not economic inevitability.

The caste dimension makes the data even more revealing. Upper castes hold 88.4% of billionaire wealth despite comprising roughly 25% of the population. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes together hold 2.6%, with zero ST representation among billionaires. This is not a coincidence. The wealth distribution maps precisely onto historical structures of exclusion that formal equality has done little to dismantle.

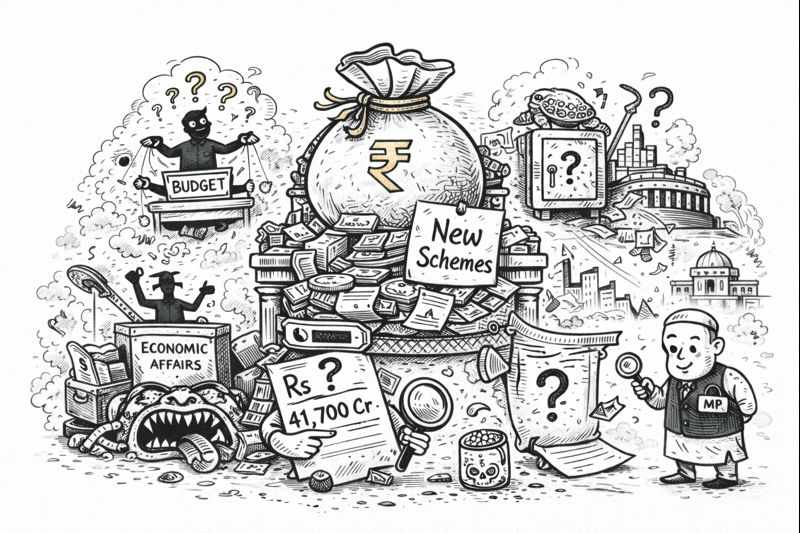

What India's Welfare State Actually Does

The government presents its welfare architecture as transformative. The claims collapse under scrutiny.

Jan Dhan Yojana opened 573 million bank accounts. This is presented as bringing banking to the masses, but it fundamentally misrepresents history. Banking was brought to rural India through bank nationalisation in 1969, Indira Gandhi's decision to nationalise 14 major commercial banks, followed by another six in 1980. That transformation created the branch network, the priority-sector lending mandates, and the institutional infrastructure that enabled mass banking. Jan Dhan accounts were opened on top of the existing public-sector infrastructure built over decades. The accounts themselves tell a story the government prefers not to highlight: 26% are now dormant, the average balance is ₹4,768, and the much-publicised overdraft facility has reached effectively no one. Opening an empty account is not financial inclusion.

PM-KISAN transfers ₹6,000 annually to farmers—₹500 per month, less than 5% of average farmer household income. The amount is calibrated to generate beneficiary counts rather than to address agrarian distress. Research shows that more than 60% of recipients spend their payments on immediate consumption because nothing else is feasible with a ₹500 monthly income. Meanwhile, the same government that distributes these tokens has frozen MGNREGA wages and allowed agricultural input costs to rise unchecked.

The Direct Benefit Transfer system is celebrated for "reducing leakage"—but much of this reduction comes from excluding legitimate beneficiaries. Aadhaar authentication failures at the point of sale have left individuals without the rations to which they are entitled. Jean Drèze and Reetika Khera have documented cases where the pursuit of "efficiency" through biometric authentication has caused genuine suffering—including starvation deaths in Jharkhand linked to ration denial. When a system's efficiency gains come partly from excluding the eligible, efficiency is not an achievement but a cruelty disguised as technocratic language.

PMAY housing was supposed to be different—housing is an asset, after all. But CAG audits reveal a programme riddled with failures: 79% of Uttar Pradesh beneficiaries received first instalments late, construction quality is abysmal, and beneficiaries frequently borrow from private moneylenders at usurious rates to complete houses that the government funding cannot finish. Many end up with debt rather than wealth—a partially built house and a loan to repay.

The pattern is consistent: announcements that generate headlines, beneficiary counts that can be recited in Parliament, and outcomes that leave the structural distribution of wealth untouched. This is not an implementation failure. This is the design working as intended.

As an economist, though, notice what all these programmes have in common: they smooth consumption flows without creating mechanisms for asset accumulation. Jan Dhan is purported to provide access to banking without requiring bank capital—26% of accounts are now dormant, the average balance is ₹4,768, and effective credit access is effectively zero through overdraft facilities. PM-KISAN's ₹6,000 annual payment represents less than 5% of the average farmer household's income and is too small for productive investment—research shows that over 60% of recipients spend the payments on immediate consumption. DBT transfers existing consumption subsidies more efficiently; it creates no mechanism for wealth building.

PMAY housing comes closest to genuine asset creation, since housing is an asset that can appreciate and be inherited. But CAG audits reveal implementation failures that undermine this potential: 79% of Uttar Pradesh beneficiaries received first instalments late, quality issues abound, and beneficiaries frequently borrow from private lenders at high interest to complete construction—often ending up with debt rather than wealth.

The Taxes That Were Removed

Understanding why India's welfare state operates as it does requires examining what was dismantled. India abolished estate duty in 1985—the tax that would have captured wealth at the moment of intergenerational transfer. The Modi government abolished the wealth tax in 2015. These were the only direct mechanisms for intergenerational wealth redistribution, and both are now gone.

The wealth tax had become largely symbolic by the time of its abolition—yielding ₹1,008 crore in 2013-14, less than 0.1% of tax revenue. But symbolic policy carries ideological weight. Its removal signalled that accumulated wealth would not be touched, that the state had abandoned even the pretence of wealth redistribution.

The 2019 corporate tax cut from 34.94% to 25.17% cost an estimated ₹1.45 lakh crore annually—0.7% of GDP. Large corporations saved ₹3.14 lakh crore over five years. This foregone revenue could have nearly doubled Education spending. The anticipated surge in private investment that was expected to justify the cut never materialised; corporate profits rose while capital expenditure remained flat.

India's tax-to-GDP ratio of 11.7% is roughly half the OECD average and below the World Bank's recommended minimum of 15% for developing countries. This constrains fiscal space for any form of redistribution—but the constraint is itself a policy choice. When Chief Economic Adviser Nageswaran responded to proposals for wealth taxation by saying, "Taxing it more will drive capital away," he offered a standard deflection without evidence. Twenty-four of 35 European nations maintain inheritance taxes. Capital has not fled Europe.

Scotland's Experiment: A Different Choice

This is where Scotland becomes instructive. In March 2025, the Scottish Government introduced the Community Wealth Building (Scotland) Bill—the first national legislation of its kind anywhere in the world. The bill, currently at Stage 2 of parliamentary scrutiny, represents an attempt to legislate wealth redistribution rather than merely hoping it happens through growth.

Community Wealth Building emerged from practical experiments, most notably in Preston, England, where the local council began redirecting procurement spending toward local businesses, promoting worker cooperatives, and using anchor institutions—hospitals, universities, local government—as engines of local economic development. The Centre for Local Economic Strategies (CLES), which pioneered the approach in the UK, documented how Preston increased local procurement from 5% to 18% of council spending and helped establish worker-owned businesses in sectors previously dominated by outside contractors.

Scotland's bill takes this local approach and makes it national policy. Under the legislation, Scottish Ministers must publish CWB statements every five years on how they will support the circulation of local wealth, anchoring community wealth building as permanent policy regardless of which party holds power. Local authorities and more than 20 public bodies—including NHS boards, universities, enterprise agencies, police, and environmental regulators—must produce action plans and implement them "so far as reasonably practicable." National guidance becomes binding.

The framework operates through five interconnected pillars: progressive procurement that prioritises social value over lowest cost; fair employment that expands living wage jobs through anchor institutions; plural ownership that grows cooperatives and social enterprises; democratic land use that promotes community ownership; and local finance that redirects investment to recirculate in communities rather than flow to distant shareholders.

The limitations deserve acknowledgement. The What Works Centre for Local Economic Growth notes that evidence on CWB's economic impacts remains limited, and the bill doesn't mandate specific targets. Critics argue that without procurement quotas or ownership requirements, the legislation may amount to strategic planning exercises rather than structural change. The Lancet study on Preston's mental health outcomes found positive effects but acknowledged methodological challenges in attributing causation.

But here is what matters for understanding India: Scotland is attempting to legislate wealth redistribution as an explicit policy goal. The bill's equality impact assessment directly addresses how wealth inequality affects protected groups. The parliamentary debate addresses questions about who owns what and how ownership patterns might be altered. This is a conversation India refuses to have.

What Actually Works: The Indian Evidence

We do not lack evidence on what interventions alter wealth distribution in India. We lack the political will to implement them.

Land reform remains the intervention with the strongest evidence base. West Bengal's Operation Barga (1978-mid 1980s) is the best-documented case. Economists Abhijit Banerjee, Paul Gertler, and Maitreesh Ghatak found the programme accounted for approximately 36% of total agricultural growth during the reform period. Registration of sharecroppers rose from 23% to 65%. West Bengal accounted for 53.2% of all land reform beneficiaries nationally—demonstrating that reform is possible when political coalitions support it.

Kerala's land reforms eliminated absentee landlords and contributed to the state's Human Development Index of 0.758—the highest in India. The comparison between states that implemented land reform and those that didn't provides natural experiments that economists have studied extensively. Banerjee and Iyer's research traces persistent inequality to colonial land revenue systems: states controlled by landed interests systematically subverted reforms, whereas states with Left political mobilisation implemented them.

One important caveat: Mookherjee et al. found that Operation Barga intensified gender inequality—male-biased inheritance increased son preference. This suggests that land reform without mandatory joint titling for women may simply transfer patriarchal wealth structures rather than transform them.

Cooperatives demonstrate another pathway. Amul transformed India from milk-deficient to the world's largest producer—24% of global production—through a three-tier cooperative structure that returns 80-85% of consumer rupee to farmers versus 33-40% in conventional supply chains. SEWA demonstrates the potential of women's cooperatives: 3 million members, more than 50 cooperatives, and a 98% loan-repayment rate. FAO research found SEWA gum collectors tripled their earnings after forming cooperatives.

The success factors are documented: strong leadership, professional management separate from political interference, democratic governance, technical support, and market linkages. These are replicable. The question is whether there is political will to replicate them at scale.

What Would Actually Redistribute Wealth

Let me be specific about what a serious wealth redistribution agenda would require, drawing on both the World Inequality Lab proposals and the Indian evidence base.

Progressive wealth and inheritance taxation. The World Inequality Lab estimates that a 2% annual wealth tax on net wealth exceeding ₹10 crore plus a 33% inheritance tax on estates above ₹10 crore—affecting only 0.04% of the population, roughly 370,000 adults—could generate 2.73% of GDP in revenue. That exceeds the entire current health budget. Exit taxes can address capital flight concerns; the twenty-four European nations maintaining inheritance taxes have not experienced capital exodus. The political obstacles are real, but the fiscal arithmetic is straightforward.

Land redistribution with mandatory joint titling. Dalit households operate just 9% of agricultural land despite comprising 18.5% of rural population. Sixty percent own no agricultural land at all. Women's land ownership remains somewhere between 5.5% and 31.7% depending on methodology—the range itself indicating how poorly we track it. Enforcement of existing ceiling laws, targeted land purchase schemes for SC/ST households, and mandatory joint titling for women would directly alter wealth stocks. The Banerjee-Iyer research shows that where land reform was implemented, it worked.

Credit access reform to address caste discrimination. NSS data shows 42% of the credit gap for Scheduled Castes and 60% for Scheduled Tribes is unexplained by economic factors—it is pure discrimination. Fisman et al.'s American Economic Review study found that when loan officers share the same caste or religion as borrowers, credit increases by 18.6%. Randomised loan officer assignment, algorithmic lending oversight, and stronger enforcement of priority sector requirements could address this. The problem is well-documented; the solutions are available.

Scaling cooperative models with protective legislation. Amul's three-tier structure has been replicated for commodities beyond dairy, where similar value-chain dynamics apply. SEWA's model of women's producer cooperatives demonstrates viability in the informal sector. What prevents scaling is not technical knowledge but political economy: cooperatives threaten existing intermediaries, who often have political connections. Protective legislation—along the lines of Scotland's CWB framework—could create space for cooperative development.

Converting consumption schemes to asset-building programmes. PM-KISAN's ₹6,000 annual transfer could be restructured as contributions to asset-building accounts that accumulate over time rather than direct consumption support. PMAY housing could be reformed to ensure the provision of actual housing with a clear title and effective quality enforcement. MGNREGA could add ownership stakes in the community assets created. These are design choices, not fiscal constraints.

The Choice

I return to where I began: my own modest financial position after twenty years of professional work. I am not poor. I have never gone hungry. I have had access to Education, healthcare, and professional opportunities that most Indians cannot imagine. And yet I have not accumulated wealth in any meaningful sense—I have no solely self-financed property, no significant investments, no financial cushion that would survive more than a few months of unemployment.

This is not primarily about my individual choices or circumstances. It reflects an economic structure in which income flows to professionals while wealth accumulates to owners. I work; others collect returns on assets. The gap between these positions widens with each passing year, and no amount of consumption smoothing programmes will alter it.

When I look at the data I helped compile for Oxfam—the billionaires doubling their wealth during a pandemic, the bottom half of India sharing 6.4% of national wealth—I see not just extreme inequality but a policy architecture designed to maintain it. We abolished estate duty. We abolished the wealth tax. We cut corporate taxes while freezing MGNREGA allocations. We refuse to conduct a caste census that would document the distribution of wealth by social group. We announce beneficiary counts while the wealth Gini reaches 85.4.

Scotland's Community Wealth Building Bill may or may not succeed. The evidence base is limited, the targets are vague, and the implementation challenges are real. But Scotland is at least asking the question: how do we alter ownership? India refuses to ask.

The Billionaire Raj now exceeds the British Raj in inequality. The phrase comes from the economists who documented it. They are being descriptive, not polemical.

The question is whether we find this acceptable.

Further Reading

Income and Wealth Inequality in India, 1922-2023: The Rise of the Billionaire Raj — Bharti, Chancel, Piketty and Somanchi's full World Inequality Lab working paper with methodology and historical series

Towards Tax Justice and Wealth Redistribution in India — World Inequality Lab policy brief on wealth and inheritance tax proposals

Survival of the Richest: The India Story — Oxfam India's 2023 report on wealth concentration and tax regressivity

Community Wealth Building (Scotland) Bill — Scottish Parliament page with bill text, policy memorandum, and committee reports

Evidence Briefing: Local Economic Impacts of Plural and Local Ownership Policies — What Works Centre for Local Economic Growth assessment of CWB evidence base

Varna Sri Raman is a development economist. She was a co-author of the Oxfam India Inequality Report 2022. She writes about economic policy, labour markets, and governance at policygrounds.press.

Write a comment ...