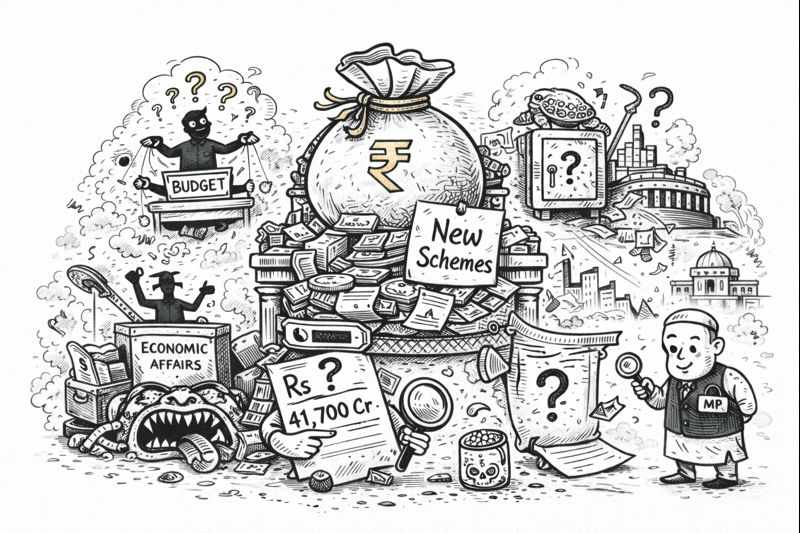

How cesses that never reach states, chronic underspending on welfare, and interest payments eating a quarter of expenditure reveal what India's budget actually does

I learned to read budgets during my time at a ministry, not the Finance Minister's speech, which is political theatre, but the Expenditure Profile and the Demands for Grants, which tell you what the government actually intends to do with money.

My colleagues would update dashboards showing "disbursement rates" and "target achievements," while I learned that the numbers obscured more than they illuminated. A scheme could show 95% utilisation by the simple expedient of reducing the denominator mid-year. A mission could be considered successful by counting outputs rather than outcomes. The art of government accounting is the art of making the uncomfortable invisible.

When the Union Budget 2025-26 was presented on 1 February, I did what I always do: I ignored the speech and went straight to the Expenditure Profile. The story it tells is quite different from the rhetorical framing. It is a story of fiscal centralisation, debt-servicing burdens, and a systematic gap between what is announced and what is actually spent.

The Gap Between Promise and Expenditure

The most revealing comparison in any Union Budget is between Budget Estimates (BE), which is what was promised, and Revised Estimates (RE), which is what was actually spent. The gap between them tells you whether announcements were serious or performative.

Consider the Jal Jeevan Mission, the flagship programme to provide piped water to every rural household. In 2024-25, the government budgeted ₹70,163 crore. The revised estimate? ₹22,694 crore. According to PRS Legislative Research, the government spent 32% of what it promised. This is not a minor shortfall. This is a programme that functionally did not happen.

The Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana tells a similar story. Combined rural and urban allocations in 2024-25 showed expenditure 44% lower than budget estimates. The government announced housing for all and then spent barely half of what it promised.

Perhaps most telling is the budget head simply called "New Schemes" under the Department of Economic Affairs. In 2024-25, this received a budget of ₹62,593 crore. The revised estimate: ₹9,068 crore. The government spent 15% of allocation. Whatever these schemes were supposed to be, they largely didn't exist.

Interest-free loans to states for capital expenditure, announced with fanfare as support for state-level infrastructure, saw allocation reduced from ₹1.5 lakh crore to ₹1.25 lakh crore in revised estimates. The Centre promised support, then quietly withdrew it.

Across all Centrally Sponsored Schemes, the revised estimates for 2024-25 show spending ₹90,622 crore lower than budgeted, a 17.9% reduction. These are not minor adjustments. This is systematic underspending on the welfare architecture that millions of Indians depend on.

The Interest Payment Trap

Open the Budget at a Glance document and one number demands attention: interest payments will consume ₹12,76,338 crore in 2025-26. This is 25.2% of total government expenditure. Before the government decides to build a road or pay a teacher or provide a pension, a quarter of its spending is already committed to servicing past debt.

As a share of revenue receipts, interest payments stand at 37%. More than a third of the Centre's own revenue, after sharing with states, goes directly to bondholders.

This ratio has improved slightly from its peak of 42% in 2020-21, but it remains a structural constraint on fiscal policy. The Ideas for India analysis documents that India's interest payments exceed 25% of general government revenues and stand at approximately 5% of GDP. This is roughly twice the emerging market average. Reducing India's interest payments to the EM average would release resources of ₹6-8 trillion, comparable to India's pre-Covid education expenditure and about three times its health expenditure.

To understand what this means in practice: every rupee spent on interest is a rupee unavailable for infrastructure, education, health, or social protection. The debt accumulated over decades now constrains what the government can do today. And because interest rates have risen globally since 2022, the effective interest rate on the Centre's debt has crossed 7% in FY26.

The Cess and Surcharge Mechanism

The most consequential fiscal innovation of the past decade has received the least public attention: the systematic expansion of cesses and surcharges at the expense of shareable taxes.

Under Article 270 of the Constitution, the Centre must share a portion of taxes collected with states. The Fifteenth Finance Commission recommended that 41% of the "divisible pool" be transferred to states. This sounds generous until you understand what the divisible pool actually contains.

Cesses and surcharges are constitutionally excluded from the divisible pool. They are taxes the Centre keeps entirely for itself. And their share has grown dramatically.

In 2011-12, cesses and surcharges constituted approximately 10.4% of the Centre's gross tax revenue. By 2020-21, this had peaked at 20.2%. It has since declined to approximately 14.5% in 2023-24. At current gross tax revenue levels, this translates to over ₹5 lakh crore annually that flows entirely to the Centre despite states bearing the bulk of expenditure responsibilities.

A National Institute of Public Finance and Policy analysis calculated that in 2022-23, the non-divisible pool accounted for about 23% of the Centre's gross tax revenues. The divisible pool has correspondingly shrunk to approximately 75-77% of gross tax revenue, down from close to 90% in 2011-12.

The practical effect: even as Finance Commission recommendations have increased the states' share from 32% (13th FC) to 42% (14th FC) to 41% (15th FC), the actual proportion of central taxes reaching states has stagnated or declined. You can offer states 41% of a shrinking pie and claim generosity while handing them less money than before.

This last budget included a telling shift. On items including solar cells and motor vehicles, customs duty had been reduced, but the Agriculture Infrastructure and Development Cess (AIDC) was introduced. The overall tax remains similar, but the composition has changed from shareable customs duty to non-shareable cess. This is fiscal centralisation through a technical mechanism.

Ministry Allocations and Welfare Stagnation

The top 13 ministries in the last budget accounted for 53% of the estimated total expenditure. Defence lead at ₹6,81,210 crore (13.4%), followed by Road Transport and Highways at ₹2,87,333 crore (5.7%), Railways at ₹2,55,445 crore (5.0%), and Consumer Affairs at ₹2,15,767 crore (4.3%).

The social sector ministries tell a more complicated story.

The Ministry of Rural Development received ₹1,90,406 crore, an 8.3% increase over revised estimates. But within this, MGNREGA allocation remains flat at ₹86,000 crore, unchanged from the previous year.

This matters because MGNREGA is not a discretionary welfare programme. It is a legal entitlement under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005. Every rural household that demands work is entitled to 100 days of employment. The Centre was legally obligated to fund whatever demand exists. Capping it at a fixed amount is, strictly speaking, a violation of the law's intent.

As LibTech India calculated, as of April 2024, MGNREGA funds had a negative balance of ₹20,751 crore. States had provided work and were owed money by the Centre. Approximately 20% of any new allocation goes to clearing pending dues from the previous fiscal year. If you adjust for arrears, MGNREGS' effective share of the budget dropped from 1.78% to 1.35%.

The consequences are visible on the ground. Wage payments are delayed, sometimes for months. Workers who complete work cannot be paid because funds have not been released. Gram panchayats stop issuing job cards because they know they cannot honour them. The 100-day guarantee becomes a 45-55 day reality.

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare received ₹99,859 crore, an 11% increase. This sounded substantial until you note that health allocation as a share of the total budget had declined from 2.16% in 2019-20 to 1.88% in 2024-25. The increase is nominal; the priority has been declining.

Education allocation stood at ₹1,28,650 crore, a 12.8% increase. But the comparison to revised estimates flattens. The revised estimate for 2024-25 was ₹1,14,054 crore, significantly below the budgeted ₹1,20,628 crore. Education spending was cut mid-year, and the "increase" in 2025-26 barely returns to where the government originally promised to be.

The Ministry of Jal Shakti showed a 93% increase to ₹99,503 crore. This appears dramatic until you recall that revised estimates for 2024-25 were ₹51,558 crore against a budget of ₹98,714 crore. The ministry underspent by nearly half. The 2025-26 allocation merely returned to where it was supposed to be the year before.

According to IDR's analysis, real allocations (adjusted for inflation) have declined for Samagra Shiksha, Jal Jeevan Mission, PM POSHAN, and the National Social Assistance Programme. Nominal increases mask real decline. The share of social sector spending in total Union government expenditure stood at 17% in 2024-25, an all-time low in the last decade. During 2014-15 to 2019-20, the share averaged 21%. The trend is unmistakable.

The Southern States' Burden

The Finance Minister announced that the Centre will transfer ₹25,59,764 crore to states in 2025-26, a 12.5% increase over revised estimates. But context matters.

Central transfers account for approximately 44% of total state revenue receipts on average. This dependence is highly uneven. Bihar depends on central transfers for approximately 72% of its revenue, Uttar Pradesh for 61%, while Tamil Nadu receives only 31% and Haryana approximately 20%.

The southern states' grievance is acute. Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh contribute approximately one-quarter of India's direct taxes. Karnataka alone contributes nearly 12%, second only to Maharashtra. Yet these five southern states receive only approximately 15.8% of central tax devolution under the 15th Finance Commission.

The Finance Commission formulas emphasise population (penalising states that controlled population growth) and "income distance" (penalising states that achieved higher growth). Succeed on development metrics and receive less money. This is the perverse incentive structure of Indian fiscal federalism.

Between FY2018 and FY2023, the Centre retained approximately ₹12 lakh crore extra via non-divisible revenues, money that would have flowed to states under a purely constitutional tax-sharing arrangement.

What a Different Budget Would Look Like

Critique is incomplete without alternatives. What would a budget that addressed these structural problems actually contain? In other words, what can we hope for on 1 February 2026?

First, cap cesses and surcharges. A constitutional amendment or at minimum a binding fiscal rule should limit non-shareable taxes to a fixed percentage of gross tax revenue. The 15th Finance Commission itself noted that approximately 18% of the Centre's tax receipts come from non-shareable cesses. A cap of 10%, phased in over three years, would return approximately ₹1.5-2 lakh crore annually to the divisible pool.

Second, make devolution formula transparent and predictable. States should know five years in advance what formula will be used to calculate their share. The current system, where the Centre can influence Finance Commission recommendations, creates uncertainty that undermines state-level planning. An independent Fiscal Council, similar to the UK's Office for Budget Responsibility, could provide non-partisan analysis of central-state fiscal relations.

Third, honour budget commitments. The systematic underspending on Centrally Sponsored Schemes is a policy choice, not an implementation failure. If a scheme is announced with a budget of ₹70,000 crore, that money should be spent or the reasons for underspending should be publicly documented. The CAG should audit not just expenditure but the gap between BE and RE, and ministries should be required to explain variances above 10%.

Fourth, fund MGNREGA as a genuine employment guarantee. The scheme is legally a demand-driven entitlement. Capping it at ₹86,000 crore while demand exceeds supply is a violation of the Act's spirit. An adequate budget would fund the scheme to provide 100 days of work to every household that demands it. Estimates suggest this would require approximately ₹1.5-2 lakh crore annually, roughly double current allocation. Of course, now there are worse problems for MNREGA, given its rapid dismantling.

Fifth, separate interest payments from productive spending in fiscal targets. The current fiscal deficit target treats all expenditure as equivalent. But interest payments are non-discretionary once debt is issued, while capital expenditure builds future capacity. A modified FRBM framework could target primary deficit (fiscal deficit minus interest payments) rather than headline fiscal deficit, creating space for growth-enhancing investment while maintaining debt sustainability.

Sixth, restore the social sector spending share. If social sector spending has fallen from 21% to 17% of the budget, returning to 21% would release approximately ₹2 lakh crore annually for health, education, and welfare. This could be achieved gradually over three years without compromising fiscal targets, particularly if accompanied by rationalisation of subsidies that benefit the non-poor.

The Politics of Numbers

Step back from individual line items and the budget's structure tells a coherent story.

The Centre has systematically expanded its own fiscal space at the expense of states through constitutional mechanisms. This is not illegal. It is constitutional design being exploited.

Accumulated debt now consumes a quarter of all government spending before a single road is built or teacher paid. This interest burden constrains what governance can accomplish.

The gap between announcements and expenditure is systematic. Schemes are budgeted, underspent, and then re-announced the following year with "increases" that merely return to previous levels. Jal Jeevan Mission spent 32% of allocation. PMAY spent 56%. "New Schemes" spent 15%. This is not accident. It is policy.

Social sector spending as a share of total expenditure is at a decade low. Real allocations for nutrition, education, and health have declined. The rhetoric of "Viksit Bharat" does not match the arithmetic of welfare funding.

The federal fiscal relationship is increasingly strained. States bear the bulk of expenditure responsibilities but have limited revenue autonomy. Southern states contribute disproportionately and receive disproportionately less. The GST regime, while improving efficiency, has further centralised fiscal authority by making states dependent on a collective pool they do not control.

A budget is not merely an accounting exercise. It is a statement of priorities, a distribution of power, and a constraint on what governments can actually do. The 2025-26 budget, beneath its announcements, revealed priorities quite different from its rhetoric. Defence and highways received increases; health and education received increases smaller than inflation. States received transfers from a shrinking pie. Interest payments consumed a quarter of everything.

Understanding the budget's architecture matters more than applauding its announcements. The numbers do not lie, but they can be made difficult to read. Reading them carefully is a civic duty.

Varna is a development economist and writes at policygrounds.press.

Further Reading

PRS Legislative Research: Union Budget 2025-26 Analysis - Comprehensive breakdown including BE vs RE comparisons

IDR: Budget 2025 and Social Sector Spending - Analysis of welfare allocations in real terms

NIPFP: Enhanced Devolution and Fiscal Space at the State Level - How cesses shrink the divisible pool

Ideas for India: India's Debt Dilemma - Analysis of the interest payment burden

Write a comment ...