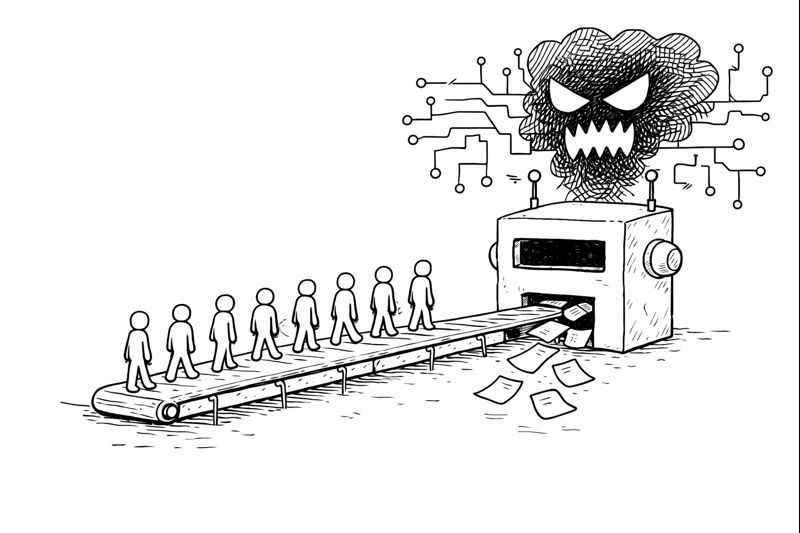

The CAG has documented systematic fraud in the Modi government's flagship skilling program. But the real scandal is what it reveals about India's squandered demographic dividend.

In the industrial outskirts of Nagpur, Bob Motgarhe remembers the day in 2017 when lecturers at his ITI suddenly asked the mechanical refrigeration students to gather outside. They were instructed to press a biometric device and leave. The same routine repeated at the end of the day. "They told me it was done to show training under PMKVY," Motgarhe later told ThePrint. "But there were no students and no training happening." Students from other departments were made to do the same. Routine inspectors, he alleged, were bribed to look the other way.

Thousands of kilometers away in Delhi's Peeragarhi neighborhood, Sunita ran a small NGO that she thought would help young people gain skills. Instead, she found herself part of an elaborate machinery of fraud. Her organization supplied students to bigger NGOs in exchange for ₹1,000 per student. On weekends, these students would be bused to a training center in Rohini to pose for photographs in well-equipped laboratories they would never actually use. "The scheme had failed completely," she told investigators. "Neither did we get paid, nor did the students get jobs." She eventually shut her NGO after being duped.

These accounts represent merely the visible surface of what the Comptroller and Auditor General has now confirmed was systematic fraud across India's flagship Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana. The December 2025 audit report, tabled in Parliament on December 18, found that of 95.90 lakh participants enrolled in PMKVY phases 2 and 3, the bank account details for 90.66 lakh were recorded as zeros, "null," "N/A," or left blank. That is 94.53% of all beneficiaries with fake or missing bank accounts. The CAG identified bank account fields containing entries such as "11111111111" and "123456." Some contained text strings, names, addresses, and special characters. One bank account number was reused for 2,106 different candidates.

But this is not merely a story of implementation failure or corruption at the margins. It is the story of how India is squandering its one-time demographic window, how the same mistakes were repeated across a decade despite explicit warnings, and how the institutional architecture of "public-private partnership" created a system designed for rent extraction rather than skill formation.

The Stakes: Why Skilling Was Supposed to Matter

Understanding the magnitude of this failure requires stepping back to consider what was at stake.

India in 2025 stands at a demographic inflection point that will not recur. With a median age of 28 years and 65% of its population under 35, the country possesses the youngest large workforce on earth. According to the United Nations Population Fund, this "demographic dividend" window, which opened around 2005-06, will remain open until approximately 2055. After that point, India begins aging. Every year of this window that passes without adequate skill formation represents permanent economic opportunity lost.

The development economics case for intensive investment in skills is straightforward. Consider what economists call the Lewis model of structural transformation: surplus labour moves from low-productivity agriculture to higher-productivity manufacturing and services. This is the pathway every successful developing economy has travelled. But this transition requires that workers possess the skills to be absorbed into modern sectors. Without skills formation, you get not a Lewis turning point but a swelling informal sector, disguised unemployment, and stalled transformation.

India's target is approximately 3.5 million people leaving agriculture annually to seek employment in the manufacturing and services sectors that require skills they do not possess. Yet this structural transformation has stalled: agricultural employment actually increased after 2019, reversing decades of gradual decline. According to the ILO's estimates cited in the India Employment Report 2024, 47% of Indian workers are underqualified for their current jobs. Among women, the figure rises to 62%. The same report found that 75% of Indian youth cannot send an email with an attachment, and 90% cannot perform basic spreadsheet operations like mathematical formulas.

These skill deficits occur against the backdrop of troubling labor market indicators. While official youth unemployment has fallen to 10.2% as of 2023-24 according to the Periodic Labour Force Survey, this figure masks deeper structural problems. The NEET rate, measuring young people not in employment, education, or training, stands at approximately 25%. Among educated youth with secondary schooling or higher, the share of the total unemployed has more than doubled, from 35.2% in 2000 to 65.7% in 2022. Youth aged 15-29 account for 83% of India's total unemployed.

The comparison with East Asian economies during their industrialisation phases makes India's situation starker. Between 1962 and 1997, South Korea trained over 2.5 million vocational trainees through programs systematically linked to its five-year economic development plans. The government identified priority sectors, projected labour requirements, and aligned training capacity accordingly. The 1976 Vocational Training Act required in-plant training for large employers; those that did not comply paid training levies that funded public vocational institutes. By 1990, 76.6% of vocational high school graduates found employment, up from 35.5% in 1965.

Taiwan and Singapore similarly built their economic transformations on the foundation of government-led but industry-aligned skill formation systems. Singapore's SkillsFuture program today maintains skills frameworks covering 38 sectors, with employer engagement mandatory in skills development. The tripartite partnership among government, employers, and unions ensures that investment in training translates into employment outcomes.

India's trajectory has diverged fundamentally. Rather than manufacturing absorbing agricultural surplus labour as predicted by the Lewis model, India has experienced a services-led growth pattern that has not created adequate employment. Manufacturing's share of employment peaked at 12.6% in 2011-12 and has since declined to 11.4% by 2022-23. This failure of structural transformation made effective skill development even more critical as a policy response.

PMKVY was supposed to be that response.

The Promise: July 15, 2015

Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched PMKVY on July 15, 2015, coinciding with the first World Youth Skills Day declared by the UN General Assembly. The Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship was established just eight months earlier, carved out as a full-fledged ministry on 9 November 2014. The 2015 National Policy for Skill Development and Entrepreneurship estimated that 40.29 crore persons across 24 sectors would need skilling by 2022.

The headline target was audacious: train 500 million (50 crore) youth by 2022 and transform India into the "skill capital of the world." Speaking at Vigyan Bhawan, Modi declared a "war on poverty" and cast India's youth as "soldiers" in this war. "India can become the world's largest provider of skilled workforce," he announced. ITIs, he promised, would gain recognition comparable to that of IITs.

The scheme's implementing agency was the National Skill Development Corporation, established in 2008 as a public-private partnership with 49% government ownership and 51% held by industry associations, including CII, FICCI, ASSOCHAM, and NASSCOM. This PPP model was meant to ensure industry relevance while government funding provided scale. NSDC would manage registration and accreditation of training providers, oversee Sector Skill Councils that would develop curriculum aligned with industry needs, and disburse funds to training partners based on enrollment, training completion, and assessment outcomes.

PMKVY 1.0 ran from July 2015 to October 2016 with a budget of ₹1,500 crore, targeting 24 lakh candidates. PMKVY 2.0, launched in October 2016, massively scaled up with a ₹12,000 crore budget and a target of one crore candidates over four years. This second phase introduced a franchising model and split implementation between a centrally managed component (75% of funds through NSDC) and a state-managed component (25% through State Skill Development Missions). PMKVY 3.0 launched in January 2021 with ₹948.90 crore, scaled back due to the pandemic. Across three phases, the total outlay reached ₹14,448.90 crore, of which ₹10,194 crore was released and ₹9,261 crore utilized.

The payment structure created incentives that proved fatal. Training partners received between ₹7,000 and ₹15,000 per trainee, depending on the course, disbursed in tranches linked to milestones. Certified candidates were entitled to a ₹500 reward through Direct Benefit Transfer. The system relied entirely on data reported by training partners via the Skill India Portal, with minimal on-site verification.

The Warnings That Were Ignored

The fraud documented by the 2025 CAG audit was not only foreseeable but foreseen. In December 2015, just months after PMKVY launched, CAG Report No. 45 of 2015 examined NSDC and the National Skill Development Fund. It found that 57% of NSDC partners failed to achieve training targets in 2010-11, rising to 77% in 2011-12, 83% in 2012-13, and 68% in 2013-14. The majority also failed placement targets. CAG recommended a "re-look at design and operations of NSDC and NSDF."

The most comprehensive early warning came from the Sharada Prasad Committee, constituted in May 2016 to review the Sector Skill Councils. Its April 2017 report was scathing. The STAR Programme, which preceded PMKVY, achieved a placement rate of 8.5%. PMKVY 1.0 managed only 18%. PMKVY 2.0, as of September 2017, reported a 12% placement rate, with only 72,858 of 600,000 skilled individuals securing employment. "All stakeholders said in one voice that the targets allocated to them were very high and without regard to any sectoral requirement," the committee reported. "Everybody was chasing numbers without providing employment to youth or meeting sectoral industry needs."

The committee, whose terms of reference were announced by PIB, made a crucial observation that would prove prophetic: "No evaluation was conducted of PMKVY 2015 to find out the outcomes of the scheme and whether it was serving the twin purpose of providing employment to youth and meeting the skill needs of the industry before launching such an ambitious scheme."

That same year, a Hindustan Times investigation found that 0.2% of training partners, just 34 institutes, had trained nearly 40% of all PMKVY candidates. One of these, the Softdot Institute near Delhi's Preet Vihar Metro Station, claimed to have trained more than 30,000 students in a single year. Investigators found it had only "five small rooms with minimal furniture." Another, Possit Skill Organisation, claimed to have trained 12,955 candidates through "franchisee arrangements with 50 other institutes" operating in "crumbling buildings on narrow bylanes."

NSDC acknowledged the problem indirectly by reducing certified training institutes from 12,181 in PMKVY 1.0 to 1,400 in PMKVY 2.0. But the fundamental architecture remained unchanged.

The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Labour, Textiles and Skill Development flagged in September 2022 that training courses and curriculum were "not aligned with industry requirements," that only 15 of 36 states had functional online management systems, and that placement tracking remained deeply problematic.

Each warning was acknowledged and set aside. Each phase of the scheme was launched before the previous phase had been evaluated.

The CAG Documents Systematic Collapse

CAG Report No. 20 of 2025 surveyed eight states: Assam, Bihar, Jharkhand, Kerala, Maharashtra, Odisha, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh. What it found went beyond implementation failures to systematic data fabrication, suggesting large-scale fraud.

The Bank Account Scandal

The bank account irregularities form the audit's most damning finding. Of 95,90,801 participants in PMKVY 2.0 and 3.0, bank details for 90,66,264 were recorded as zeros, "null," "N/A," or blank. That is 94.53% of all enrolled beneficiaries.

Among the 5,24,537 records that did contain bank details, the CAG found 12,122 unique account numbers reused for 52,381 candidates. The reuse patterns were extraordinary: Reuse Pattern Number of Accounts Used 6-10 times 238 Used 51-100 times 39 Used 101-1,000 times 34 Used 1,001-2,000 times 4 Used 2,106 times 1. A single bank account number was recorded for 2,106 different candidates.

Email and Mobile Number Fabrication

Email verification proved equally problematic. When CAG surveyors sent emails to 4,330 candidates, 36.51% bounced. Of the 171 responses received from delivered emails (a response rate of 3.95%), 131 came from the same email addresses or from training partners and training centres, not from actual trainees.

Mobile numbers showed similar fabrication. CAG found approximately 87,000 beneficiaries with irregular mobile numbers such as "9999999999" or "1000000000."

Biometric Attendance: The Fiction of Verification

Biometric attendance, supposedly mandatory through the Aadhaar-enabled biometric attendance system since April 2018, proved largely illusory. Only 13% of batches showed compliance with AEBAS since 2018. Physical inspections found that 24 of 90 training centres surveyed had biometric devices that were either not installed or not working. Geotagging was unavailable in 84% of inspection cases.

Paper Centers and Ghost Trainees

The CAG found training centres marked "active" on portals that were physically shuttered during inspection. In Bihar, 3 of 10 training centres inspected were closed. In Odisha, 1 of 17 was closed. In one Bihar district, payments of ₹5.72 lakh continued to flow to a centre after the CAG had already reported its closure.

Perhaps most disturbing was the photographic evidence of fraud. The audit found identical photographs used for multiple beneficiaries across Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan. The same photograph was documented for batch #57241 in Gaya, Bihar and batch #67518 in Bahraich, Uttar Pradesh.

Specific Fraud Cases

Neelima Moving Pictures, a proprietary business not registered with the Registrar of Companies, claimed to have trained 33,493 participants in 21 job roles across 8 states between January and November 2020, a period when it was reportedly non-operational due to COVID-19.

Jaipur Cultural Society claimed to have trained thousands of people in the media sector and submitted newspaper clippings with dates erased or altered, including references to the impossible date of "31 February 2020."

Placement Outcomes

The placement outcomes confirmed the scheme's failure as a skill development intervention. Of the 56.14 lakh candidates certified under Short-Term Training and Special Projects, only 23.18 lakh were placed, representing 41%. Even this figure is questionable given the data integrity failures throughout the system, and 34 lakh certified candidates remain unpaid for their ₹500 reward to date.

The Parallel Ecosystem: Who Benefited?

The ThePrint investigation published in January 2026 documented the ecosystem that enabled this fraud.

The fraud operated through multiple levels. Small NGOs served as intermediaries, supplying students to larger training partners in exchange for kickbacks of approximately ₹1,000 per student. The scheme was marketed to operators as a "money-making opportunity" requiring minimal investment: secure a 300-square-foot room, gather students, click photographs, and reuse images across multiple reporting cycles. Weekend photo sessions at well-equipped centres created documentation of training that never occurred.

Preet Luthra's experience captures the betrayal. He invested ₹10 lakh to establish a training centre in Rohini, securing all required certifications and a 3+ star rating. He never received any training targets. Eventually, larger NGOs began approaching him to rent his facility for weekend photo sessions. "They would bring students, take pictures in our labs, and leave," he told ThePrint. He eventually sold his building.

Vikas, a trainee who enrolled in mobile repair training at a centre in Delhi's Vasant Kunj in 2018, described months of waiting. Trainers rarely appeared. When they did, classes were perfunctory. He struggled for more than a year to obtain his certificate. He remains unemployed.

The October 2025 blacklisting of 178 training partners across India began revealing who had benefited from the scheme's structural vulnerabilities. The state-wise distribution was telling:

State Blacklisted Entities

Uttar Pradesh 59

Delhi 25

Madhya Pradesh 24

Rajasthan 20

Others 50

The ministry analysis found that in 122 of 178 cases, the identity of the training partner differed from that of the training centre, suggesting proxy operations and front organisations.

A KPMG forensic audit conducted in 2023 had identified a ₹1,082 crore crisis within NSDC itself. The audit found loan approvals with "repetitive justifications lacking due diligence," new funds allocated to cover previous defaults, and 58 training centers listed for loans that did not physically exist. Forged signatures were copied from unrelated files. Loan repayment rates had fallen as low as 12% by 2021. An estimated 40% of training certificates lacked proper trainee verification.

Ved Mani Tiwari, who served as NSDC CEO from March 2021, reportedly recovered ₹214 crore and attempted to clean up operations. A whistleblower dossier titled "1000 Crore Scam in NSDC" was allegedly sent to ministers and the PMO. Tiwari was abruptly removed from his position in May 2025. In August 2025, NSDC filed a police complaint against two senior officials for mishandling government property and funds.

The Government Response: More of the Same

On 7 February 2025, the Union Cabinet approved continuation and restructuring of the Skill India Programme with an outlay of ₹8,800 crore through 2026. PMKVY 4.0 received ₹6,000 crore of this allocation. The ministry claimed "transformational changes" including Aadhaar-authenticated e-KYC for candidate registration, 400 new courses in AI, 5G, cybersecurity, and drone technology, and integration with the Skill India Digital Hub for lifecycle tracking.

These claims require scrutiny. The CAG audit covering PMKVY 4.0 implementation through October 2024 found continuing problems:

1.18 lakh underage candidates had been certified for 365 job roles

Invalid (175) or repeated (2,263) mobile numbers were still being recorded

More than 2.72 lakh instances of "null" email addresses persisted

More than 3.08 lakh repeated email addresses remained in the system

The work experience field remained unimplemented

A Parliamentary Standing Committee report submitted in March 2025 revealed that against a target of 45 lakh trainee certifications for financial year 2024-25, only 19.17 lakh had been achieved as of March 3, 2025, a shortfall of 25.83 lakh, well under 50% of target. The committee noted that only 47 of every 100 enrolled candidates ultimately received certification.

Most tellingly, the committee emphasised that placement details under PMKVY 4.0 are the "real barometer for measuring success," but that placement tracking had been formally delinked from the scheme. The government has stopped even pretending to measure whether training leads to employment.

The Structural Problem: Design for Failure

The PMKVY scam is not an aberration. It is the predictable outcome of an institutional architecture that prioritised scale over substance, certification over competence, and rent extraction over skill formation.

Consider the fundamental design choices:

The PPP Model: The 51% private ownership of NSDC was meant to ensure industry relevance. Instead, it created a system in which public funds flowed to private training partners without effective accountability to either government or industry. The training partners had no stake in whether their graduates found employment. Their revenue came from enrollment and certification, not outcomes.

The Franchising Model: PMKVY 2.0's expansion of the franchising model led to a proliferation of training centres, many operated by intermediaries who had never delivered training before. The 84% concentration of targets among 10% of Training Partners, while 50% of TPs got only 2% of targets, created an oligopoly of well-connected operators.

The Short-Term Training Model: The 150-600-hour courses that dominate PMKVY cannot produce the competencies that employers actually need. South Korea's vocational programs ran for 1-2 years. Germany's apprenticeships last 2-3 years. India's 3-month courses produce certificates, not skills.

The Disconnection from Industrial Policy: Unlike East Asian models, where skill development was systematically linked to industrial policy through five-year plans, India's PMKVY operated in a vacuum. There was no micro-level skill-gap assessment. There was no coordination with the manufacturing policy. Training happened in whatever courses training partners chose to offer, regardless of labour market demand.

The Verification Vacuum: The system depended entirely on self-reported data from training partners through the Skill India Portal. Biometric attendance was mandated but not enforced. Third-party assessors were often missing or untraceable (97% in some analyses, according to CAG). Inspectors were allegedly bribed. The architecture assumed good faith from actors whose incentives pointed toward fraud.

NITI Aayog CEO BVR Subrahmanyam acknowledged the structural failure in May 2025 when he suggested that "the government should consider handing over skilling institutions to the private sector." Industrial Training Institutes should be handed to respective industries, he proposed, because "only industry has a handle on what the contemporary relevant skills are at a local level."

This represents an implicit admission that a decade and ₹14,000 crore had failed to deliver on the promises made. But it also misdiagnoses the problem. The issue was not insufficient privatisation but the absence of accountability structures. Handing ITIs to industries without those structures would simply relocate the rent extraction.

What Would Actually Work

Genuine skill development reform would require confronting uncomfortable questions about the political economy that the government has thus far avoided.

Training Must Be Linked to Employment Outcomes: The decision to "delink" placement tracking from PMKVY 4.0 moves in precisely the wrong direction. Payment to training providers should be substantially weighted toward demonstrated placement in jobs relevant to the training provided. This requires independent verification mechanisms rather than self-reported data. South Korea achieved this through employment insurance databases that tracked where vocational graduates actually worked.

Employers Must Have Skin in the Game: South Korea's training levy system was effective because noncompliant employers faced financial penalties. India's current system treats employers as passive beneficiaries of government-funded training rather than active participants in skill formation. A training levy on firms above a certain size, with credits for those who provide structured workplace learning, would align incentives.

The Short-Term Training Model Requires Abandonment: The 150-600-hour courses that predominate in PMKVY cannot produce the competencies employers actually need. The Industrial Training Institute system, with courses lasting 1-2 years, produces better outcomes but suffers from outdated curricula and inadequate capacity. Reform should expand ITI capacity by developing updated curricula through genuine industry partnerships, rather than adding another layer of short-term programs.

Data Integrity Must Be Treated as Infrastructure: The scale of fabrication documented by CAG indicates not just implementation failure but the absence of basic verification systems. Aadhaar-linked registration, real-time biometric attendance with independent monitoring, and bank account verification before payment should be baseline requirements, not aspirational reforms.

The PPP Model Must Be Restructured or Abandoned: Either genuine employer involvement through sectoral bodies with enforcement powers, or direct government implementation through reformed ITIs, would yield better outcomes than the current hybrid model. The worst of both worlds, public funding without public accountability and private implementation without market discipline, has proven a recipe for fraud.

The Window Narrows

India's demographic dividend window will not remain open indefinitely. The share of the working-age population is projected to peak around 2041. After that point, the country will begin ageing without having achieved the economic transformation that enabled countries such as South Korea and Taiwan to become wealthy. The window, which UNFPA estimates to be 50 years in total, has already been open for two decades.

The consequences of skill formation failure compound over time. Industry estimates suggest India could face a shortage of tens of millions of skilled personnel by 2030. Accenture estimates that the skills gap will result in $1.97 trillion in foregone GDP growth over the coming decade. Each cohort of young Indians who enter the workforce without adequate skills becomes increasingly difficult to train later in life, even as the occupational requirements they face continue to evolve.

The India Employment Report 2024 documented a troubling reversal. After decades of slow but steady transition from agricultural to non-agricultural employment, the share of workers in agriculture actually increased after 2019, from approximately 42% to 45.8% by 2022-23. Nearly two-thirds of new employment since 2019 has been in self-employment and unpaid family work, categories that typically indicate disguised unemployment rather than genuine opportunity.

Female labour force participation presents a particular challenge. While official statistics show FLFPR rising from 23.3% in 2017-18 to 41.7% in 2023-24, much of this increase reflects women entering low-productivity self-employment and unpaid family work rather than quality employment. Women spend eight times more time on domestic and caregiving work than men. The government's Viksit Bharat 2047 target of 70% female workforce participation cannot be achieved without fundamentally restructuring both the care economy and the skill formation system.

The PMKVY scam represents more than financial malfeasance. It represents a decade of policy failure during a demographic window that will not reopen. The warnings were explicit and repeated: CAG in 2015, the Sharada Prasad Committee in 2017, investigative journalism throughout, Parliamentary Standing Committees regularly. Each warning was acknowledged and set aside. Each phase of the scheme was launched before the previous phase had been evaluated. Rs 8,800 crore more was allocated in February 2025, two months before the CAG report documented the full scale of the fraud.

The ₹14,450 crore spent on PMKVY from 2015 to 2022 produced, according to CAG's conservative assessment, a 41% placement rate among certified candidates, with 94% of beneficiary data compromised to the extent that fundamental questions about whether training actually occurred cannot be answered. Meanwhile, 47% of India's workers remain underqualified for their jobs; 25% of youth are not in employment, education, or training; and the structural transformation from agriculture to manufacturing, which would create mass employment, has stalled.

What cannot be recovered is time. The median age of the Indian population is 28 years. In fifteen years, that person will be 43, past the age when basic skill formation occurs most readily. The country's demographic structure will look different. The window will be closing.

Congress spokesperson Kannan Gopinathan, a former IAS officer, described it as a "massive scam" and a "betrayal of youth" at a press conference in December 2025. He demanded a thorough investigation. But an investigation alone cannot recover the lost decade. The question is not whether India can afford to invest in genuine skill development. Given what is at stake, the question is whether it can afford another decade of the alternative.

The demographic dividend does not wait. It is a one-time transition that other Asian economies captured through deliberate state capacity, and India is squandering it through institutional decay. If the current trajectory continues, India will not reap a demographic dividend; it will face what demographers grimly call a "demographic disaster": a large population of unemployed, unmarried young men with limited economic prospects, the ingredients for social and political instability.

Skill India was supposed to prevent that future. Instead, it became another vehicle for the extraction of public resources by private actors, another scheme where metrics were optimised while outcomes collapsed, another betrayal of the promise that brought young Indians to training centres that existed only on paper.

Varna Sri Raman is an independent development economist. She writes at policygrounds.press.

Write a comment ...