The Economic Survey 2026 proposes ministerial vetoes over RTI. This is the third phase of dismantling the law that exposed lakhs of crores in corruption and made welfare delivery accountable to citizens.

I spent New Year's at Barefoot College in Tilonia with Aruna Roy, one of the chief architects of India's Right to Information Act. The college sits in the same Rajasthan landscape where, three decades ago, Roy and the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan began demanding that poor peasants be allowed to see the government records that determined their wages. The walls still carry the slogans. The files from those early struggles still exist. The people who fought for transparency when it meant sitting in the sun for forty days outside a district collectorate are still there, still watching what happens to the law they extracted from a reluctant state.

What they are watching now is its slow strangulation.

I have spent more than two decades observing governance processes in various capacities, both within and outside the system. When I worked at the MOHUA on the Swachh Survekshan and the Livability Index, I updated dashboards daily at a government Bhawan, watching numbers rise while the infrastructure those numbers supposedly measured remained unchanged underground. When I co-authored the Oxfam India Inequality Report in 2022, I examined how welfare flows reached citizens while wealth stocks remained untouched. I have written about how MGNREGA's implementation became a case study in the gap between announcement and reality, how cesses collected in the name of health and Education never reach the states, how India's "cleanest cities" were killing their residents through infrastructure neglect that dashboards could not measure.

RTI is the thread connecting all of these observations. It is the mechanism through which citizens discovered that the numbers on official portals did not match the roads in their villages. It is how activists documented that MGNREGA wages on muster rolls exceeded wages actually paid to workers. It is how journalists verified that PM CARES expenditures remained opaque, even as the government demanded transparency from others. The systematic erosion of RTI is not separate from the systematic erosion of accountability in welfare delivery, environmental protection, and fiscal federalism. It is the same project.

I thought about those conversations when I read the Economic Survey 2025-26, tabled on 29 January 2026. The Survey proposes that India "re-examine" its Right to Information Act to protect "brainstorming notes, working papers, and draft comments until they form part of the final record of decision-making." It suggests shielding "service records, transfers, and confidential staff reports from casual requests." Most alarmingly, it floats "a narrowly defined ministerial veto, subject to parliamentary oversight."

The Survey frames this as aligning with "global best practices." It cites Tony Blair's regret about Britain's Freedom of Information Act. It cites U.S. exemptions for interagency memos. It does not mention that India's RTI, which once ranked second globally in independent assessments, still ranks ninth worldwide with 126 points, while the United States' FOIA ranks 78th. It does not explain why adopting weaker laws constitutes "best practice."

This is the third phase of a systematic dismantling that began in 2019. Each phase has been presented as a technical adjustment. Together, they are strangling the most powerful accountability tool Indian citizens have ever possessed.

The right that came from the fields

India's RTI Act did not originate in Parliament. It emerged from the drought-stricken villages of Rajasthan, where poor peasants discovered that fighting for wages required fighting for information.

The Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan was founded on Labour Day 1990 by Aruna Roy, a former IAS officer who had resigned from the service, Nikhil Dey, and theatre artist Shankar Singh. They established a mud house in Devdungri village, Rajsamand district, and worked with landless labourers and marginal farmers on minimum-wage campaigns.

The breakthrough came when MKSS activists helped workers demand muster rolls from local panchayats. The records revealed systematic fraud: ghost workers who never existed, wages disbursed for work never performed, materials purchased at inflated prices, entire projects that existed only on paper. A worker told Aruna Roy, "There is some magic in these official records, and until we get these records, we won't get our legitimate wages."

The first Jan Sunwai, or public hearing, was held in Kot Kirana village on December 2, 1994. MKSS read the official expenditure records aloud to the assembled villagers, who could testify whether the recorded works actually existed. Roads that were never built. Wells that were never dug. Wages for labourers who had never worked. The methodology was revolutionary in its simplicity: let the people who were supposed to benefit verify whether benefits reached them.

The slogan that emerged captured the democratic essence: "Hamara Paisa, Hamara Hisab." Our Money, Our Accounts. Public funds belong to citizens who deserve accountability.

The historic 40-day dharna at Beawar's Chang Gate in April 1996 compelled Rajasthan to amend its Panchayati Raj Rules, granting residents the right to inspect expenditure documents. State-level RTI laws proliferated: Tamil Nadu became the first state to pass legislation in May 1997, followed by Goa, Rajasthan, Karnataka, and Maharashtra.

The National Campaign for People's Right to Information, established in 1996 with over 100 civil society organisations, drafted model legislation. When the UPA government took power in 2004, Aruna Roy served on the National Advisory Council that shaped the bill. The national RTI Act, passed on May 11, 2005, received Presidential assent on 15 June, and came into force on October 12, 2005.

This history matters. The RTI was not a gift from enlightened rulers. It was extracted by the poor, who understood that without information, they could not claim what was rightfully theirs.

Information asymmetry and the economics of accountability

There is a reason development economists care about transparency beyond democratic principles. When bureaucrats know things citizens do not, corruption flourishes.

The work of Nobel laureates George Akerlof and Joseph Stiglitz on information asymmetry applies directly here. When officials possess information advantages over citizens, Akerlof's "lemons problem" emerges in governance: corrupt officials crowd out honest ones, welfare leakages multiply, ghost beneficiaries proliferate.

This is not a theoretical abstraction. The Shanta Kumar Committee, drawing on NSSO data, documented that 46.7 per cent of PDS grain was lost to leakage in 2011-12. Not misallocated. Not delayed. Lost. Diverted. The grains allocated to poor households ended up elsewhere. How do we know this? Activists armed with RTI could compare official allocation records with actual disbursements, document the gap between what was left in government warehouses and what reached fair price shops, and verify whether the names on beneficiary lists matched actual recipients.

Amartya Sen's famous observation that "no substantial famine has ever occurred in any independent and democratic country with a relatively free press" explains why RTI matters for development. During the Great Leap Forward famine, local officials suppressed negative information, leading authorities to believe they had 100 million metric tons of grain in stock when in fact there was none. When information is hidden, people die. When information flows, course corrections become possible.

Sen's insight goes beyond famine prevention. The World Health Organisation estimated 4.7 million excess deaths in India during the COVID pandemic, roughly ten times the official count. That gap is not just a statistical discrepancy. It is a policy failure made possible by opacity. If local mortality data had been available through RTI from the pandemic's start, the pressure for course correction would have come sooner.

Jean Drèze, co-author with Sen of foundational development texts and architect of MGNREGA, built RTI principles directly into India's flagship employment guarantee program. Sections 17 and 23 of MGNREGA mandate social audits in which official records obtained through RTI are publicly reviewed and verified against reality. This was deliberate. Drèze understood that welfare programs cannot function without accountability.

The Andhra Pradesh social audit model demonstrated that RTI-enabled verification detected fraud while empowering rural workers. As Drèze noted, MGNREGA "gave bargaining power to rural workers," including bonded labourers escaping slavery and women earning independent income. None of these functions can operate without access to information to verify wages and work records.

The economist Rohit Azad, whose work on fiscal federalism I have drawn on extensively, makes the same point about Centre-state transfers. When the Centre collects cesses and surcharges that do not flow to states, citizens cannot verify this diversion without access to budget documents and disbursement records. When GST compensation is delayed or denied, state governments need RTI-documented trails to press their case.

The share of cesses and surcharges in gross tax revenue nearly doubled between 2011-12 and 2020-21, peaking at over 20 per cent before declining to 14.5 per cent by 2023-24. None of this money is shared with states. In absolute terms, cesses and surcharges collected over ₹4.7 lakh crore in 2021-22. That is money taken from the divisible pool, money that would otherwise have flowed to state governments to fund schools, hospitals, and welfare programs. RTI is how citizens and state governments can document this fiscal centralisation. Without it, the Centre can claim success while starving states of resources.

RTI is not merely a procedural nicety. It is an infrastructure for development.

What RTI exposed: Corruption worth lakhs of crores

Between 2005 and 2019, over 32 million RTI applications were filed across India, with annual filings rising from under a million in early years to 5-6 million by the late 2010s. This citizen-driven transparency infrastructure exposed corruption of staggering scale.

The 2G Spectrum Scam, estimated at ₹1.76 lakh crore by CAG, was substantially documented through RTI applications. Activist Subhash Chandra Agrawal's requests revealed that Telecom Minister A. Raja held an undocumented 15-minute meeting with the Solicitor-General, and the Finance Ministry's file notes indicated that the spectrum could have been auctioned at substantially higher prices. Activist Vivek Garg obtained nearly 600 PMO documents critical to understanding the scandal.

The Commonwealth Games, with a total expenditure of ₹70,000 crore and riddled with irregularities, were exposed when the Housing and Land Rights Network's RTI revealed that the Delhi government had diverted ₹744 crore from Dalit welfare funds to CWG projects. The Adarsh Housing Society scandal emerged when activists used information requests to reveal that a 6-storey building for war widows had become a 31-storey tower in which politicians, bureaucrats, and military officials obtained flats at below-market rates. Maharashtra Chief Minister Ashok Chavan resigned.

The Coalgate scandal, estimated at ₹1.86 lakh crore by CAG, involved RTI-obtained documents that led the Supreme Court to declare 214 coal block allocations illegal.

For welfare delivery, RTI-enabled social audits detected MGNREGA wage fraud and PDS leakages. Research documented 46.7 per cent PDS leakage at the all-India level in 2011-12, with RTI-backed verification driving reforms that reduced this substantially. Kerala's RTI-documented fraud in 345 ration shops led to license cancellations.

Put this in development economics terms. India's 2024-25 budget allocated ₹2.05 lakh crore for food subsidies, ₹86,000 crore for MGNREGA, and ₹60,000 crore for PM-KISAN. That is over ₹3.5 lakh crore in direct welfare transfers. If even 20 per cent of this is lost to corruption and leakage, that is ₹70,000 crore per year stolen from the poor. RTI is the primary tool citizens have to verify whether money allocated in their name actually reaches them. Without it, the government can announce schemes, claim credit, and never be held accountable for the gap between allocation and delivery.

Every rupee recovered through RTI-exposed corruption is a rupee that can reach intended beneficiaries. Every ghost worker eliminated from the MGNREGA rolls means wages are available for actual workers.

Development economists measure welfare by whether resources reach those who need them. A ₹100 transfer to a poor household has a marginal propensity to consume of nearly 1; that money goes directly into the local economy. A ₹100 transfer stolen by a contractor, middleman, or corrupt official has a marginal propensity to consume of approximately 0.3; the remainder ends up in savings, real estate, or capital flight. RTI is the tool that shifts welfare spending from the second category to the first. Destroying RTI is not just an attack on transparency. It is an attack on the effectiveness of every social program the government runs.

Phase One: The 2019 Amendment that made commissioners government servants

The first attack came with the RTI (Amendment) Act 2019, passed on 22 July (Lok Sabha) and 25 July (Rajya Sabha), with no referral to the Parliamentary Standing Committee despite opposition demands. The amendment targeted the independence of Information Commissioners through seemingly technical changes.

The original RTI Act, 2005, granted the Chief Information Commissioner status equivalent to that of the Chief Election Commissioner, a constitutional functionary, with a fixed 5-year tenure (or until age 65) and a monthly salary of ₹2,50,000. Information Commissioners received Election Commissioner equivalence. These protections were deliberately embedded in the parent statute rather than delegable rules.

The 2019 amendment substituted these fixed statutory protections with a single phrase: "such term as may be prescribed by the Central Government." The actual RTI Rules 2019, notified on 24 October 2019, revealed the damage: tenure reduced from 5 years to 3 years, salary parity with the Election Commission eliminated.

Most critically, the Central Government now controls both Central AND State Information Commissioners. This is a clear federalism violation. State Commissioners were always paid from State Consolidated Funds. The Centre has no constitutional basis to determine its conditions of service. Yet the amendment grants Delhi authority over who may serve as Information Commissioner in Tamil Nadu, Kerala, or West Bengal.

Minister of State Jitendra Singh assured Parliament the government would not have "unbridled powers" and would not change tenure "after every two years." The notified rules proved these assurances hollow. Congress MP Shashi Tharoor called it "not an Amendment Bill but an Elimination Bill."

Jairam Ramesh's PIL challenging the amendment has remained pending in the Supreme Court since January 2020. The Centre has failed to file a substantive response despite judicial criticism.

Phase Two: The DPDP Act's surgical strike on Section 8(1)(j)

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023 delivered a more surgical attack through Section 44(3), which amended RTI's Section 8(1)(j) by deleting 81 of its 87 words.

The original provision exempted personal information from disclosure only when it had "no relationship to any public activity or interest" AND only if it would cause "unwarranted invasion of privacy." It included a public-interest override permitting disclosure when "the larger public interest justifies" it. A proviso guaranteed citizens' information rights equivalent to those of Parliament members.

The amended Section 8(1)(j) reads simply: "information which relates to personal information." Full stop.

Gone is the public interest override. Gone is the proviso equating citizen and parliamentary access. Gone is the balancing test that courts had consistently applied. The amendment creates a blanket exemption for all "personal information," a term so broad under DPDP's definition ("any data about an individual who is identifiable") that it can encompass virtually any government record containing any individual's name.

The practical damage is severe. Asset declarations of public servants, salary and benefits of officials, transfer orders and service records, performance records, names of contractors who built collapsed bridges, wilful bank loan defaulters, electoral bond purchaser information, welfare beneficiary lists: all can now be blocked by invoking "personal information."

The Bill was passed on August 7-9, 2023, during the Manipur no-confidence motion debate with minimal scrutiny. In March 2025, more than 120 members of the INDIA bloc, including Rahul Gandhi, Akhilesh Yadav, and Supriya Sule, wrote to the IT Minister, Ashwini Vaishnaw, demanding the repeal of Section 44(3).

The Internet Freedom Foundation's fact-check of Minister Vaishnaw's defence documented that the government's claims that RTI remained intact were contradicted by the legislative text.

Former Delhi High Court Chief Justice A.P. Shah's open letter in July 2025 described the changes as a "seismic shift" that would "dismantle RTI Act's core purpose of democratic accountability."

Phase Three: The Economic Survey's ministerial veto proposal

The Economic Survey 2025-26 takes the dismantling further. Under the heading of "re-examination" to "align with global best practices," it proposes three more restrictions.

First, exempting "brainstorming notes, working papers, and draft comments until they form part of the final record of decision-making". This creates the deliberative process exemption that India deliberately avoided in 2005. It would shield exactly the file notings that exposed the 2G and Coalgate irregularities.

Second, protecting "service records, transfers, and confidential staff reports from casual requests." This legitimises the DPDP amendment's damage, ensuring that citizens cannot discover which officials approved contracts for collapsed bridges or made transfers in exchange for bribes.

Third, the Survey floats "a narrowly defined ministerial veto, subject to parliamentary oversight, to guard against disclosures that could unduly constrain governance." This is the most dangerous proposal of the three.

The Survey selectively presents international comparisons while omitting context. It invokes former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair's regret about FOI ("You idiot. You naive, foolish, irresponsible nincompoop") without noting that Blair's hostility stemmed from FOI's exposure of Labour Party scandals. It cites the UK ministerial veto (Section 53) without noting that the 2015 Supreme Court held the veto violated fundamental principles of the rule of law and effectively rendered the provision ineffective.

It references the American deliberative process exemption (Exemption 5) without noting that Congress passed the 2016 FOIA Improvement Act specifically to curb "increasing agency overuse and abuse" of this exemption, which added a 25-year time limit.

The Survey claims the goal is "not to dilute spirit, but align with global best practices, incorporate evolving lessons, keep anchored to original intent." However, the original intent, established by MKSS activists in Rajasthan villages, was that poor citizens should be able to verify whether public funds intended for them actually reached them. How does a ministerial veto serve that intent?

Congress President Mallikarjun Kharge responded: "After killing MGNREGA, is it RTI's turn to get murdered?"

The institutional collapse: Commissions without commissioners

The legislative attacks come alongside institutional starvation. The Central Information Commission, with sanctioned strength of 11 (1 Chief plus 10 Commissioners), currently operates with only 2 Commissioners. Nine posts lie vacant. The CIC Chief post has been vacant seven times in eleven years, including the current vacancy since September 2025.

The numbers tell the story. 4,05,509 appeals pending across all 29 Information Commissions as of June 2024, an 86 percent increase from 2.18 lakh in 2019. State Information Commissions in Jharkhand (defunct since May 2020, over four years), Tripura (since July 2021), and Telangana (since February 2023) have been completely non-functional. Estimated disposal times in functioning commissions reach absurd levels: 24 years in West Bengal, 4-5 years in Bihar and Chhattisgarh.

The penalty provision, RTI's enforcement teeth at ₹250 per day up to ₹25,000 maximum, has been rendered meaningless. Penalties were not imposed in 95 percent of cases where they were potentially applicable. The institutional message to officials is clear: obstruction carries no consequences.

The Supreme Court has stepped in repeatedly. In Anjali Bhardwaj v. Union of India (2019), the Court directed timely appointments, warning that vacancies "negate the very purpose" of RTI. In October 2023, CJI Chandrachud said governments are "ensuring that the right to information becomes a dead letter." The government has ignored both rulings.

The "no data available" government

Administrative obstruction adds another layer to legislative erosion. Analysis of Central Information Commission annual reports reveals that 47 per cent of RTI rejections nationally in 2020-21 invoked Section 8 exemptions, with Section 8(1)(j) the most commonly cited. The PMO's use of an undefined "Others" category for 2,227 rejections in 2015-16 alone, a category that does not exist in the law, demonstrates how creative obstruction has become.

Critical governance information has been denied. Electoral bonds data was denied through RTI until the Supreme Court struck down the scheme as unconstitutional in February 2024. The demonetization cabinet note was denied despite CIC penalty show-cause notices, eventually revealing RBI Board members' warnings of negative GDP effects. PM CARES Fund operations were declared outside RTI entirely despite handling thousands of crores in pandemic relief.

The Delhi High Court's August 2025 ruling in the PM degree case, citing the DPDP Act to deny RTI access, showed that courts are already using the amendments to block disclosure before the rules are even notified.

RTI activist Anjali Bhardwaj observes: "The Data Protection Act can make RTI ineffective." That appears to be the point.

107 activists killed, zero protection implemented

Physical violence enforces what legislation and obstruction cannot. At least 107 RTI activists have been killed since 2005, according to Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative documentation. Over 180 physical assaults and 187 threats or harassment incidents have been recorded.

Amit Jethwa, a Gujarat lawyer exposing illegal mining involving BJP MP Dinu Solanki, was shot outside the Gujarat High Court in 2010. Despite a CBI conviction in 2019, sentencing Solanki to life imprisonment, the Gujarat High Court acquitted all the accused in May 2024, with 25 witnesses turning hostile. Shehla Masood, who filed over 200 RTI applications investigating tiger deaths and illegal mining, was shot in her car in Bhopal in 2011. Satish Shetty, the first RTI activist murdered in India, was stabbed in Pune in 2010 for exposing land scams.

After activist Vipin Agarwal was shot dead in Bihar in September 2021 for exposing land-grabbing mafias, his 14-year-old son committed suicide six months later due to police inaction in arresting the killers.

The Whistleblower Protection Act 2014, passed by Parliament and receiving Presidential assent on 9 May 2014, has never been operationalised. Rules were never notified. An amendment bill introduced in 2015 to dilute provisions lapsed when the 16th Lok Sabha dissolved. The message is clear: expose corruption at mortal risk, with zero legal protection.

What they don't want you to know

The pattern of denials reveals what the government considers most sensitive. Electoral bonds, which the Supreme Court found violated constitutional rights by enabling anonymous corporate donations to parties, were shielded from RTI for seven years. The identities of donors, the timing of donations relative to government contracts, and the concentration among companies facing regulatory action. All was hidden until judicial intervention forced disclosure.

Demonetization, which wiped out 86 per cent of currency in circulation with four hours' notice, generated RTI requests seeking the cabinet note, RBI board discussions, and economic impact assessments. The eventual disclosures revealed that RBI directors had warned of negative GDP effects and that the stated rationale (eliminating black money) was contradicted by the 99.3 per cent currency return rate.

COVID-19 death data, in which RTI requests documented discrepancies between official counts and actual mortality, remain contested. The World Health Organisation estimated 4.7 million excess deaths in India during the pandemic. Official figures remain a fraction of that.

PM CARES, established in March 2020 to receive pandemic donations, including those diverted from PMNRF, has been declared outside RTI jurisdiction. Its expenditures, beneficiaries, and trustees' decision-making processes are all opaque. A fund that received over ₹10,000 crore in public donations operates with less transparency than a village panchayat.

The pattern is clear: information that would enable democratic accountability for major policy decisions is exactly what the government works hardest to conceal.

The irony of "global best practices."

The Economic Survey's citation of international models inverts their lessons. The UK's ministerial veto, Section 53 of the Freedom of Information Act 2000, has been used only seven times since the law's passage. The 2015 Supreme Court ruling in R (Evans) v Attorney General found that the veto "cut across two constitutional principles and fundamental components of the rule of law." The judgment effectively killed the provision: a government minister cannot simply override a court decision because he disagrees with it.

The United States' deliberative process exemption, FOIA Exemption 5, has been so abused that Congress passed the FOIA Improvement Act of 2016 specifically to curb agency overreach, adding a presumption of openness and a 25-year time limit on withholding. American scholars describe the exemption as "the most controversial and most litigated FOIA exemption."

Sweden, which the Survey also cites, enacted the world's first freedom-of-information law in 1766. Its tradition of transparency is so embedded that the principle of public access to official documents has constitutional status. Citing Swedish exceptions without acknowledging Swedish constitutional commitment to transparency is selective to the point of deception.

There is something absurd about the Survey's framing. When India wants to claim global standing, it invokes comparisons with developed democracies. When India wants to restrict democratic rights, it also invokes comparisons with developed democracies. The selective citation works in only one direction: towards less transparency.

The Survey does not mention that, as originally enacted, India's RTI Act ranked second globally in the Global Right to Information Rating and still scores higher than the United States (78th), the United Kingdom (43rd), and Canada (53rd). It does not acknowledge that the 2005 drafters deliberately studied international exemptions and chose not to include several that the Survey now proposes. The public interest override, the limited personal information exemption, and the absence of ministerial vetoes: these were features, not bugs. They were deliberate choices made by legislators who understood what transparency meant in Indian conditions.

India's RTI Act, as originally enacted, represented a considered balance drawing on international experience while adapting to Indian conditions. The 2005 drafters were aware of deliberative process exemptions. They chose not to include them. They knew about ministerial vetoes. They chose not to include them. These were deliberate decisions, not oversights.

To invoke "global best practices" while proposing to regress from India's own achievements is not reform. It is dismantling disguised as modernisation.

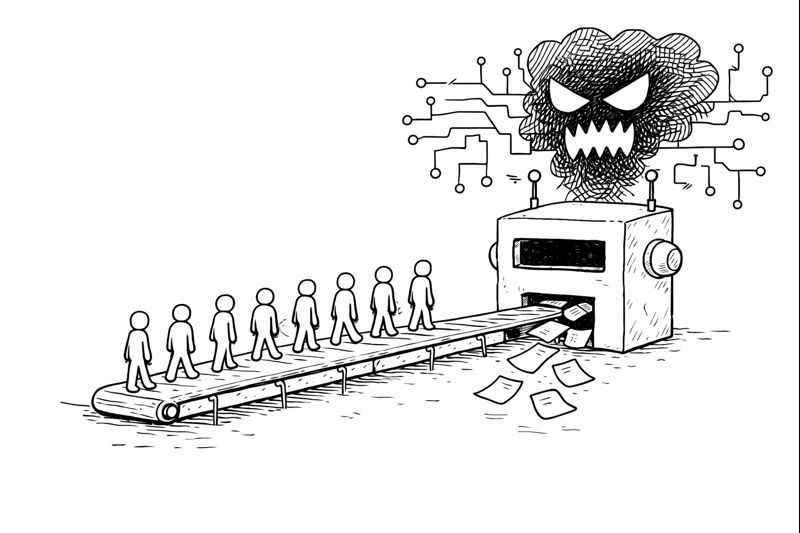

Twenty years after Aruna Roy and the MKSS extracted transparency rights from reluctant bureaucracies, the infrastructure they built is being dismantled brick by brick. The 2019 Amendment removed commissioner independence. The 2023 DPDP Act eliminated the public interest override. The 2026 Economic Survey proposes ministerial vetoes and deliberative exemptions.

Each change is presented as a technical adjustment. Together, they transform what was once among the world's strongest freedom of information laws into what former CIC Shailesh Gandhi calls "Right to Deny Information."

The damage to development outcomes is not abstract. Social audits require information access. MGNREGA verification requires muster roll transparency. PDS leakage detection requires access to the beneficiary list. Corruption investigation requires file noting examination. Every accountability mechanism that RTI enables becomes weaker when information can be withheld on the grounds of "personal information," "deliberative process," or ministerial discretion. The fiscal multiplier of welfare spending depends on whether that spending reaches the poor. RTI is how we know if it does. Without RTI, we are back to taking the government's word for it.

The pattern is familiar to anyone who has watched Indian governance over the past decade. The same logic that starved MGNREGA of funds while claiming success through dashboard metrics, that declared cities "clean" while their water pipes rotted underground, that collected cesses for education and health that never reached classrooms and hospitals, now applies to the transparency infrastructure itself. The form is preserved while the substance is hollowed out.

RTI erosion is particularly dangerous because it is self-perpetuating. Without functioning Information Commissions, citizens cannot document the erosion. Without access to file notings, researchers cannot prove that decisions were made to weaken transparency. The tool designed to expose government failures is being disabled so that government failures become harder to expose.

Consider what we would not know without RTI. We would not know that RBI directors warned against the demonetization's economic effects. We would not know that electoral bonds allowed companies facing regulatory action to make anonymous donations to the ruling party. We would not know that PM CARES received thousands of crores while lacking any formal accountability mechanism. We would not know the identities of wilful defaulters protected by banks that received public bailouts.

The 42 million applications filed since 2005 represent citizens who believed they had a right to know how their government spent their money. The lakhs of crores in corruption exposed represent what accountability can achieve when citizens have tools. The 107 activists killed represent the price some paid for using those tools.

The question now is whether those tools will survive.

What can be done now

The damage is severe. It is also reversible if there is political will.

The Supreme Court has pending cases that could restore what has been taken. Jairam Ramesh's PIL challenging the 2019 Amendment has been pending before the Supreme Court since January 2020, with no substantive hearing. The Court's October 2023 observation that governments are "ensuring that the right to information becomes a dead letter" was ignored. The government simply did not fill the vacancies. A definitive ruling on the independence of the commissioner could undo the 2019 damage, but only if the Court stops issuing warnings and begins issuing mandamus.

Section 44(3) of the DPDP Act is subject to a constitutional challenge. More than 120 members of the INDIA bloc have demanded its repeal. If the amendment violates Article 19(1)(a)'s right to information, as Justice A.P. Shah and other constitutional experts argue, judicial review could restore the public interest override. The Delhi High Court's premature invocation of DPDP in the PM degree case suggests that this issue will soon reach the Supreme Court.

Parliament retains the power to amend. The Economic Survey's proposals are not legislation. They require bills to be introduced, debated, and passed. The 2019 Amendment passed without referral to the Standing Committee despite opposition demands. A future Parliament could restore commissioner independence, reinstate the public interest override, and reject ministerial vetoes. What legislation damaged, legislation can repair.

At the state level, Information Commissions in Kerala, Maharashtra, and other opposition-governed states can demonstrate what functional transparency infrastructure looks like. States can fill vacancies promptly, impose penalties consistently, and clear backlogs aggressively. Comparative performance across states creates political pressure for national reform.

Civil society organisations that built the RTI movement remain active. The Satark Nagrik Sangathan, the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, and dozens of local groups continue to file applications, document denials, and train new activists. The MKSS continues to conduct Jan Sunwais in Rajasthan. But they are fighting with broken tools. When Information Commissions do not function, when appeals take 24 years to resolve, when penalties are never imposed, the most dedicated activist cannot make the system work.

Individual citizens retain the power to file. Every RTI application is a data point. Every denial is a record. Every appeal that reaches a Commission documents institutional failure. The government cannot claim that RTI is functioning if Commission backlogs continue to grow, if disposal times stretch to decades, and if denial rates climb. Filing applications, even when denied, creates the evidence base for reform.

The Budget session beginning February 1, 2026, offers an immediate opportunity. If the Economic Survey's RTI proposals are incorporated into the Budget legislation, the opposition in Parliament may seek a Standing Committee referral, public consultation, and an impact assessment. The 2019 Amendment was passed in days. That speed need not be repeated.

What remains

In Rajasthan villages in the 1990s, poor peasants fighting for minimum wages discovered that they could not verify their own payments without access to official records. Their slogan became a movement, their movement became a law, their law became a model for the world. The demand was simple: if the government spends public money in our name, we should be able to see where it goes.

The government's answer, increasingly, is "no."

Hamara Paisa, Hamara Hisab. Our Money, Our Accounts.

The fight that began in Devdungri village continues. The terrain has shifted from panchayat offices to Parliament to the Supreme Court. The opponents have moved from local officials to the Information Commissions to the Economic Survey itself. But the fundamental question remains unchanged: does a citizen in a democracy have the right to know how her government uses her money?

For three decades, India's answer was yes. Whether that answer survives depends on whether enough citizens still care to demand it.

Varna is a development economist and writes at policygrounds.press.

Further Reading

20 Years of RTI Act: Systematic Undermining of the Transparency Regime, Down To Earth

Section 44(3) and the Systematic Dismantling of the RTI Act, Internet Freedom Foundation

RTI Act: The Right to Know Turns 20, Association for Democratic Reforms

Tenure and Salaries under RTI Rules 2019, PRS Legislative Research

Write a comment ...