Indore won "India's cleanest city" eight consecutive times while its pipes rotted underground. The gap between dashboard governance and ground reality is now measured in bodies.

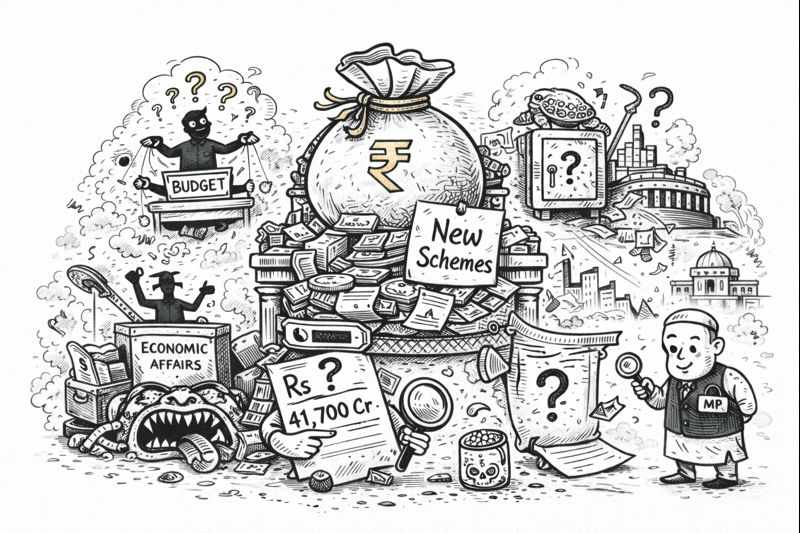

I spent a couple of years walking into Nirman Bhawan, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs headquarters in central Delhi, working on the Livability Index and Swachh Survekshan studies for the Smart Cities Mission. My job, in essence, was dashboards. I helped design the metrics that would rank Indian cities, determine which municipal commissioners received praise and which were transferred, and generate press releases announcing India's urban transformation.

I remember the discussions about what to measure. Solid waste management was easy—you could count garbage trucks, weigh refuse at processing plants, and survey households about collection frequency. Open defecation-free status had clear metrics. Citizen feedback could be collected through mobile applications. We measured what was visible, countable, and photographable for the Prime Minister's Twitter account.

What I don't remember anyone measuring: the condition of underground water pipes. The age of sewage infrastructure. Whether drinking water mains ran parallel to—or crossed—drainage lines. The functionality of water treatment plants versus their installed capacity. The last time pipeline joints were inspected for corrosion.

I thought about this when Indore killed its residents in late December. India's cleanest city for eight consecutive years. The poster child of Swachh Bharat. The crown jewel of every dashboard I ever helped populate. A public toilet had been built directly over a 30-year-old water main, without a septic tank, and raw sewage had been seeping through a corroded pipeline joint into drinking water for months. E. coli, Salmonella, Vibrio cholerae—the full suite of waterborne killers—showed up in 35 of 51 samples.

The official death toll is 7. The government paid compensation to 18 families. Local journalists counted 14-17 bodies. When asked about the discrepancy, Chief Minister Mohan Yadav—naturally a BJP member —said: "We don't delve into statistics."

I spent years delving into statistics. I helped build the statistical apparatus that declared Indore a success. And I know, now, and in fact knew it then too, that we were measuring the wrong things—not by accident, but by design. I did call it out, but I was just a young researcher, and it was easy to ignore.

What We Choose to Count

The thing about Swachh Survekshan is that it was always meant to be winnable. The BJP needed victories it could photograph. Garbage trucks with "Swachh Bharat" painted on the side. Selfie points at waste processing plants. Open defecation-free certificates to hand out at rallies. The survey was designed around metrics that could show rapid improvement—precisely because rapid improvement in visible cleanliness is achievable if you're willing to spend money on it.

Underground infrastructure doesn't photograph well. Pipeline replacement doesn't make for good optics. You can't inaugurate a corroded joint that didn't burst. And so the ranking that made Indore famous—that let the BJP claim urban transformation, that became the template for "New India" governance—systematically ignored the invisible rot beneath the surface.

When the 2019 CAG audit documented that Indore was losing 65-70% of its water supply to leakage—2,873 reported cases with repair delays of 22-182 days—no one in Nirman Bhawan agreed to incorporate infrastructure integrity into the Swachh Survekshan rankings. The audit found 5.33 lakh households without potable water, with a per capita supply of 58 litres, against a target of 150 litres. But Indore kept winning. The dashboard said so.

According to The Tribune, the file requesting replacement of the defective pipes in Bhagirathpura had been pending on the same desk at the municipal corporation for four months. It moved, finally, when people started dying.

Ghanta

Urban Development Minister Kailash Vijayvargiya—whose constituency includes Bhagirathpura, the neighbourhood where residents died—was asked by journalists on December 31 about the contamination. His response, captured on video: "Ghanta." Slang for "nonsense." Congress workers across Madhya Pradesh started carrying bells to the protests. An SDM in Dewas was suspended for using the word "ghanta" in an official order—a government more concerned with vocabulary control than the bodies in Bhagirathpura.

Rajendra Singh, the "Waterman of India" who won the Ramon Magsaysay Award for his groundwater conservation work, called it what it was: a "system-created disaster." "To save money," he said, "contractors lay drinking water pipelines close to drainage lines. Deep-rooted corruption is to blame. If such a tragedy can occur in the country's cleanest city, it shows how serious the condition of drinking water supply systems must be in other cities."

He's right, of course. In the twelve months before Indore, 5,500 people fell sick and 34 died from contaminated tap water across 26 Indian cities. Gandhinagar: 150+ children hospitalized with typhoid. Jajpur, Odisha: 2,000+ cases, 11 deaths from cholera. Bengaluru, Gurugram, Patna, Chennai, Guwahati, Raipur—the list goes on. The government's own Pey Jal Survekshan found that only 46 of 485 cities surveyed achieved a 100% pass rate for water quality. Ninety percent of urban India is drinking water that fails safety standards at least some of the time.

The Mission That Shrank

The BJP's flagship water scheme is called Jal Jeevan Mission—"water is life." Launched on 15 August 2019, it promised functional household tap connections to all 19.32 crore rural households by December 2024. The dashboard shows 80.95% coverage. Celebration-worthy numbers.

The government's 2022 Functionality Assessment tested whether those connections actually deliver water that meets three criteria: adequate quantity (55+ litres per capita per day), regular supply, and potable quality. The finding: 62% functional. Not 80%. Sixty-two.

This is the gap I learned to see in Nirman Bhawan—the gap between what gets announced and what gets delivered, between coverage and functionality, between a tap connection and water that won't kill you. The dashboard shows 15.67 crore households with taps. The ground shows roughly half of them working properly. But which number makes it to the press release?

The budget tells the real story. The 2024-25 allocation for Jal Jeevan Mission was ₹70,163 crore. The revised estimate? ₹22,694 crore. A 68% cut. The Expenditure Finance Committee has recommended reducing JJM's overall outlay by ₹41,000 crore, thereby shifting the gap to states that can't afford it. The original December 2024 deadline has been extended to 2028. Finance Minister Sitharaman called this "extending a successful mission." The bodies in Bhagirathpura suggest a different interpretation.

A Parliamentary question response revealed that as of September 2024, 11,975 rural habitations still had contaminated water sources—68% of them in Rajasthan alone. Of 66 lakh water samples tested in 2024-25, 3.3 lakh were contaminated. Remedial action was taken on 59% of contaminated samples. The other 41%? Still contaminated, presumably. Still being drunk.

In Jammu & Kashmir, a former IAS officer flagged irregularities amounting to ₹13,000 crore in the implementation of the JJM. Of 3,253 schemes, only 330 records were submitted to the House Committee. Inspections identified non-functional reservoirs, excluded households, leaking pipelines, and schemes that were fraudulently shown as completed in 2023 under JJM. In November 2025, the Central government imposed penalties totalling ₹129.27 crore on seven states for irregularities, with Gujarat alone accounting for ₹120.65 crore. Odisha's CAG audit found ₹148.75 crore in suspected diversions through engineers' personal bank accounts—ATM withdrawals, UPI transfers, and mobile recharges—using project funds intended for water infrastructure.

Then there's the Ganga. The Namami Gange Mission, launched in 2014, has received approximately ₹42,500 crore to clean India's holiest river. Actual expenditure: around ₹18,739 crore, or 43%. Sewage treatment capacity created: 52% of the target. And the water quality?

At all seven monitored stations in Bihar, faecal coliform levels reached 92,000 MPN/100ml—37 times the permissible limit for bathing. During the Maha Kumbh 2025 in Prayagraj, faecal coliform levels were reportedly 1,400 times above permissible limits. Pilgrims took holy dips in what was, by any scientific measure, a sewage stream.

The fundamental math: India's cities generate 72,368 million litres per day (MLD) of sewage. Installed treatment capacity: 31,841 MLD. Actual treatment: 20,235 MLD. Which means roughly 72% of urban sewage flows untreated into water bodies. This isn't a failure of the Namami Gange Mission specifically—it's a structural reality that no amount of press conferences can change.

What Disappears

What we measure shapes what we see. What we choose not to measure disappears.

The 2023 CGWB Annual Ground Water Quality Report found that 19.8% of groundwater samples exceed nitrate limits—440 districts, 56% of the country. Fluoride exceeds limits in 9.04% of samples across 370 districts. Arsenic in 3.55% across 152 districts, concentrated in the Gangetic plain, where 26 million people in West Bengal alone are at risk.

Sixty-six million Indians suffer from fluorosis. In arsenic-affected areas, 15% of examined populations show skin lesions and cancers. But these conditions develop slowly, over years. They don't make headlines. They're not counted in any dashboard I ever helped build.

The ICMR estimates 37.7 million Indians are affected by waterborne diseases annually. 1.5 million children die from diarrhoea-related causes. 73 million working days lost. $600 million in direct economic costs—not counting the incalculable cost of children growing up stunted, of adults too sick to work, of families bankrupted by medical bills for diseases that safe water would have prevented.

Over the five years to 2022, waterborne diseases caused 10,738 officially recorded deaths—cholera, diarrhoea, typhoid, and viral hepatitis. Uttar Pradesh alone accounted for 22% of diarrhoeal deaths. These are official numbers, which means they're almost certainly undercounts. When Chief Minister Yadav says he doesn't "delve into statistics," he's describing a governance philosophy, not just a press conference gaffe.

The Capital's Water

I live in Delhi now, where I think about water every day. The DJB supplies water that my four-year-old has learned to question. "Is this safe?" he asks, with the matter-of-factness children have when they've absorbed adult anxieties without fully understanding them.

It's not a rhetorical question. Of 25+ public water testing laboratories in Delhi, only 2 have NABL accreditation—the gold standard for testing reliability. Eight percent. CAG audits found that DJB Labs tests only 16 of the 46 required parameters. Tests for arsenic, lead, copper, radioactive materials, and biological contaminants? Not conducted.

The Yamuna—Delhi's primary water source—has a BOD of 127 mg/L across the city, exceeding the safe limit of 3 mg/L. Faecal coliform at 1.5 million MPN/100ml against a limit of 500. Dissolved oxygen at some points: zero. The river is biologically dead. Delhi's 22-km Yamuna stretch—less than 2% of the river's length—contributes 76-80% of total pollution.

Delhi loses 51-58% of its water supply before it reaches consumers. The Supreme Court noted that 52.35% of Delhi's water is either wasted or pilfered. In areas such as Sangam Vihar—population over a million—residents receive 45 litres per person per day, below the norm of 135, and spend ₹1,000+ per month on private tankers whose water quality is not tested.

This is the national capital. The seat of government. Where the ministers who announce Jal Jeevan Mission, Namami Gange, and Swachh Bharat live and work. And even here, water kills.

The Exception

The thing is, we know safe water is achievable. Puri did it. In July 2021, the temple town became India's first city to provide 24/7 potable tap water to all 32,000 households. Water meeting IS 10500 and WHO standards, from every tap, around the clock.

They shifted from groundwater to surface water. They replaced old pipes with food-grade pipes. They installed 100% metered connections. They built SCADA real-time monitoring. They reduced non-revenue water from 55% to 15%. They trained 947 women from Self-Help Groups—Jalsathis—to handle meter reading, billing, water quality testing, and consumer complaints.

The Smart Cities Mission for which I worked documented Puri's success. We wrote case studies about it. We held conferences. The Mission closed in March 2025, leaving 427 projects worth ₹10,718 crore incomplete; only 18 of 100 cities had completed all projects, and no further budgetary allocation was made. The Puri model was never scaled. It remains an exception that proves the rule.

Why? Because Puri had something most Indian cities lack: political will sustained over years, from a Chief Minister (Naveen Patnaik) willing to prioritise unglamorous infrastructure over ribbon-cutting optics. The BJP has governed India for 11 years. In that period, they've built a Ram Mandir, renamed cities and schemes, and launched dashboards, missions, and surveys. They've become very good at measuring what appears to be success. They remain unable—or unwilling—to do the slow, invisible, expensive work of ensuring that turning on a tap doesn't risk your life.

The file requesting pipe replacement in Bhagirathpura sat on a desk for four months. Now 3,000 km of pipeline has been replaced, and water supply has resumed. The families of the dead have received ₹2 lakh each. Minister Vijayvargiya has stopped saying "ghanta." The Madhya Pradesh High Court, hearing PILs on the crisis, observed that access to clean drinking water is a fundamental right.

None of this brings back five-month-old Avyan Sahu, born to parents who waited ten years for a child, killed by infant formula mixed with tap water from India's cleanest city.

I think of Avyan when I reflect on my time at Nirman Bhawan. I think about the metrics that were chosen and the infrastructure that was ignored. I think about the press releases announcing Indore's eighth consecutive victory, about the ministers who tweeted congratulations, about the dashboard I helped update showing India's urban transformation. I think about what was measured and what everyone there chose not to see.

My four-year-old still asks, before drinking water anywhere outside our home: "Is this safe?"

I still don't have a good answer.

Data sources: CAG audit reports (2019, 2023, 2025); Jal Jeevan Mission dashboard and Functionality Assessment 2022; CGWB Annual Ground Water Quality Report 2023; CPCB River Quality Reports; ICMR waterborne disease data; Parliamentary questions; Down To Earth, IndiaSpend, India Water Portal investigative reports.

Write a comment ...