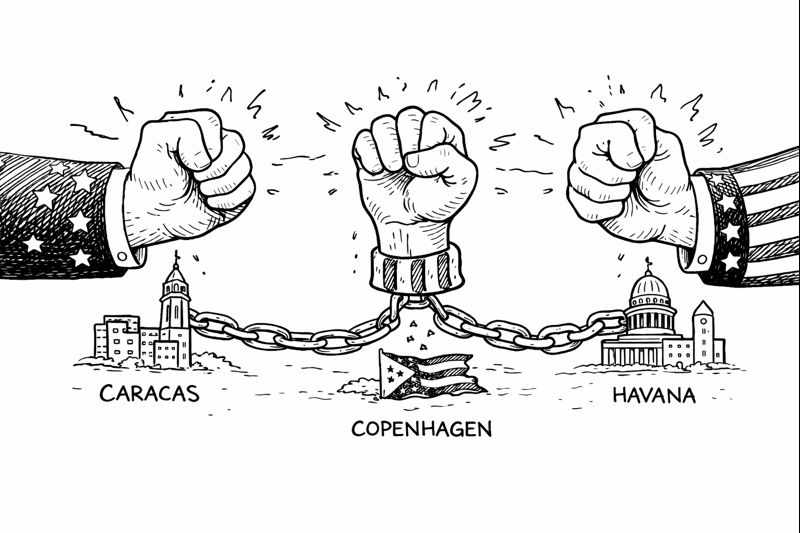

Trump captures Maduro, threatens to annex Greenland, and strangles Cuba with secondary sanctions. The system that took 47 years to build is being dismantled in weeks.

My son asked me last week why countries follow rules. He is twelve, and his class had been discussing the United Nations. I found myself explaining the Bretton Woods system, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, and the World Trade Organisation. How the world's most powerful nation, having witnessed the catastrophe of the 1930s, chose to bind itself to rules it helped write. How this self-binding made cooperation possible. How smaller countries could trade with larger ones, knowing that disputes would be settled by law, not by gunboats.

He asked if this was still true.

I did not know how to answer.

On 7 January 2026, President Donald Trump told the New York Times: "I don't need international law." Asked what would stop him from taking Greenland by force, he replied: "My own morality." Four days earlier, American special forces had captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro in a pre-dawn raid, killing at least 32 Cuban soldiers. Trump announced at Mar-a-Lago: "We are going to run the country." On 29 January, he signed an executive order threatening tariffs on any nation that sells oil to Cuba.

Three actions in three weeks. A military intervention justified by drug trafficking indictments. Threatened annexation of a NATO ally's territory. Secondary sanctions weaponise trade access against third countries. Together, they represent something more significant than policy shifts. They represent the explicit abandonment of the legal architecture that has governed international economic relations since 1947.

For development economists, this matters beyond geopolitics. The rules-based trading system was never just about tariffs. It was about whether small countries could participate in global commerce without submitting to great power coercion. Whether disputes would be settled by panels applying agreed principles or by the one who had more aircraft carriers.

How the rules-based order was built

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, signed in 1947 by 23 countries, embodied two core principles. First, most-favoured-nation treatment: any tariff concession granted to one trading partner must be extended to all GATT members. No discrimination, no special deals for favoured allies. Second, bound tariff schedules: countries commit to maximum tariff rates negotiated multilaterally and cannot unilaterally raise them without compensation.

These principles were not altruistic. They were insurance against the 1930s. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930 raised American import duties to record levels. Trading partners retaliated. Global trade collapsed by two-thirds between 1929 and 1934. The resulting economic devastation fed fascism, militarism, and war.

The GATT framers, meeting while bombed cities still smouldered, designed a system to prevent repetition. The United States, holding half the world's manufacturing capacity and two-thirds of its gold reserves, agreed to bind itself to rules. Smaller countries could challenge American trade practices before dispute panels. The hegemon accepted legal constraint because the alternative, history had demonstrated, was catastrophe.

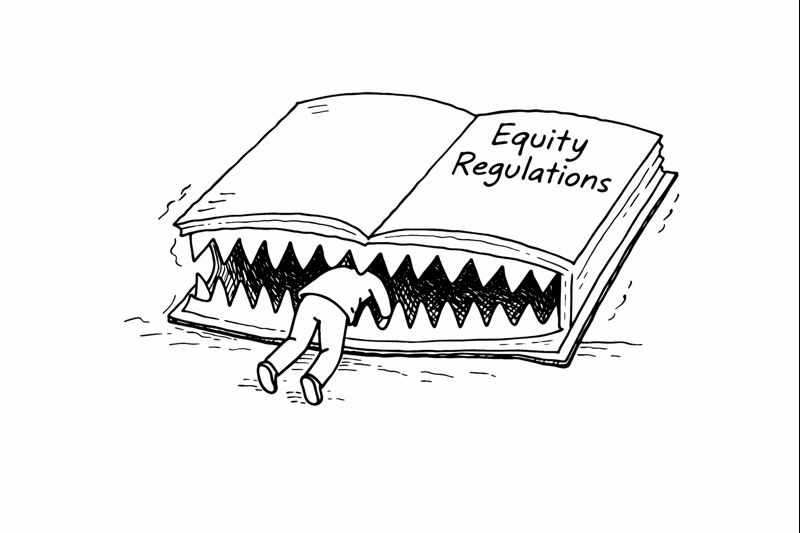

The World Trade Organisation, established in 1995, strengthened this architecture. The Dispute Settlement Understanding established a quasi-judicial process: panels of trade-law experts, binding rulings, and an Appellate Body to ensure consistency. Countries won and lost based on legal arguments, not power. The United States lost cases. It complied with adverse rulings. The system worked.

Until 10 December 2019, when the Appellate Body collapsed. The United States, frustrated by rulings against its trade remedies, blocked appointments of new members. Without a quorum, the body ceased functioning. The WTO's enforcement mechanism died.

Trump's second term makes explicit what the Appellate Body's collapse implied: the United States no longer considers itself bound by multilateral trade rules. The EU established a Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration arrangement as a workaround, now including 57 WTO members. But this covers only willing participants. For countries not in the MPIA, there is no appellate review. Disputes end at the panel stage, inviting strategic non-compliance.

Why rules matter for development: The economics of predictability

The collapse of rules-based trade governance is not merely a legal abstraction. It strikes at the economic foundations that enabled the most successful poverty reduction in human history. Between 1990 and 2015, over a billion people escaped extreme poverty, with trade integration a central driver. This occurred within a framework that allowed small countries to access large markets on predictable terms.

The economics of trade-led development require long time horizons. A Bangladeshi garment manufacturer deciding whether to invest in new facilities needs confidence that American or European buyers can import the finished products. The investment takes years to recoup. Uncertainty about market access kills the investment before it begins. This is why development economists emphasise the credibility of trade commitments. Predictable rules convert risky long-term bets into calculated business decisions.

Consider the garment sector, which lifted Bangladesh out of agrarian poverty. In 1980, garment exports were negligible. By 2024, they accounted for 85% of exports and employed 4 million workers, most of them women who had previously had no formal employment. This transformation depended on the Multi-Fibre Arrangement's quotas and, later, on the WTO's phasing them out on a known schedule. Buyers in New York and Paris could sign multi-year contracts knowing the trade regime would remain stable. Factory owners in Dhaka could borrow against those contracts to expand production.

The alternative is visible in earlier eras. Before GATT, bilateral trade deals depended on political relationships that could shift with each election. Countries too small or strategically unimportant to matter politically found themselves excluded from markets regardless of their comparative advantage. The phrase "most-favoured-nation" treatment captured the shift: trade concessions granted to one partner would automatically extend to all. Size and political leverage stopped mattering. What mattered was price and quality.

Most-favoured-nation treatment meant a Vietnamese textile producer competed with an Italian one on terms of efficiency, not political favour. The Vietnamese firm might have lower labour costs. The Italian firm might have superior design capabilities. But both were subject to the same tariff schedule, and neither faced arbitrary discrimination. This levelled playing field allowed poor countries to convert their comparative advantages into development opportunities.

The dispute settlement mechanism reinforced this. When the United States tried to exclude certain Chinese clothing in 2000, China challenged the action before a WTO panel. China won. The United States complied. This was not charity. It was the law. A developing country with 13% of global GDP challenged the hegemon, which accounted for 30%, and prevailed on legal grounds. The precedent mattered enormously for every small country watching: legal rights would be enforced regardless of power disparities.

India's pharmaceutical sector followed a similar trajectory. Until 2005, India's patent law did not recognise pharmaceutical product patents, only process patents. This allowed Indian manufacturers to reverse-engineer Western drugs and produce generics at fractions of the original price. The WTO's TRIPS agreement required India to bring its patent law into compliance by 2005. India negotiated hard for the transition period, won flexibilities for compulsory licensing, and ultimately complied on a defined schedule. The certainty allowed both Indian generic manufacturers and Western pharmaceutical companies to plan. Indian firms knew when they would need to innovate rather than imitate. Western firms knew their intellectual property would eventually receive protection.

This is why the current breakdown matters. When Trump threatens 26% tariffs on India contingent on political concessions, pharmaceutical companies in Mumbai cannot know whether their investments will yield returns. When American officials can simply ignore WTO rulings, Indian exporters cannot count on legal protections they were promised. The economics of long-term investment require stable expectations about future conditions. Arbitrary rule changes destroy that stability.

The cost shows up in employment. India's merchandise exports to the United States totalled $77 billion in 2024. At an average productivity of $15,000 per worker in export sectors, this represents approximately 5 million Indian jobs dependent on US market access. A 26% tariff would make many of these exports uncompetitive. The workers would not simply find equivalent employment elsewhere. Export-oriented manufacturing pays better than informal sector work precisely because it connects to global value chains. Destroying that connection pushes workers backwards down the development ladder.

The same logic applies to every developing country with significant exports to the US. Vietnam's exports to the United States reached $114 billion in 2024. Mexico's totaled $466 billion. Bangladesh sent $7 billion in garments alone. Every billion dollars of exports represents tens of thousands of jobs for workers who have few alternatives at comparable wages. Trade is not abstractions about comparative advantage. It is mothers in Dhaka who earn enough to send their daughters to school. It is farmers in Vietnam's Central Highlands connecting to coffee buyers in Seattle. It is the difference between subsistence and modest prosperity for hundreds of millions of people.

When rules disappear, power determines outcomes. Countries with large domestic markets or strategic military importance can negotiate acceptable bilateral deals. Countries that are small, poor, or strategically irrelevant cannot. This is not speculation. It is how international commerce worked before 1947. The GATT was created precisely because the alternative had been tried and found catastrophic.

Venezuela: Force replaces law

The 3 January operation in Venezuela represents the first forcible capture of a sitting head of state by the United States since Manuel Noriega in 1989. Special forces raided Maduro's compound at 2:01 AM local time, extracted him, and flew him to Florida to face drug trafficking charges. At least 32 Cuban soldiers providing security were killed.

The legal basis offered was a 2020 narcoterrorism indictment. The precedent established is something else: that the United States claims authority to arrest foreign leaders on its own criminal charges, using military force on foreign soil, without the consent of the government involved.

International legal scholars identify three violations. First, the use of force violated Article 2(4) of the UN Charter, which prohibits "the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state." Second, the operation violated Venezuelan sovereignty. Third, the killing of Cuban soldiers potentially violated international humanitarian law.

The United States invoked self-defence against narcotics trafficking under Article 51 of the UN Charter. This stretches the legal concept beyond recognition. Self-defence permits the use of force in response to an armed attack, not to enforce domestic criminal law abroad. The Washington Office on Latin America notes: "Whatever one thinks of Nicolás Maduro, the United States' military action violates international law and sets a dangerous precedent for the use of force."

Trump's statement from Mar-a-Lago made clear that legal niceties were not the point. "We are going to run the country," he said. "For how long? I don't know. We'll see." This is not law enforcement. It is an imperial administration announced without euphemism.

The regional response has been muted. Colombia's President Gustavo Petro condemned the operation but took no concrete action. Brazil expressed "concern" while noting that Maduro's government had lost legitimacy. Mexico recalled its ambassador. The Organisation of American States, once the embodiment of non-intervention principles, issued a statement notable mainly for what it did not say.

The development cost: Regional burden of forced displacement

The intervention in Venezuela illustrates how imperial economics socialises costs among the weakest parties. The United States captures Maduro, claims to be "running" Venezuela temporarily, and will eventually arrange a government more to its liking. The economic and humanitarian costs fall elsewhere.

UNHCR estimates that 7.7 million Venezuelans have fled the country since 2015, constituting one of the largest displacement crises globally. The neighbouring countries absorbing these refugees bear the costs that the intervention exacerbates. Colombia hosts 2.9 million Venezuelan refugees, equivalent to nearly 6% of Colombia's population. Peru hosts approximately 1.5 million people, about 5% of its population. Ecuador, Chile, Brazil, and Panama each host hundreds of thousands more.

These are not wealthy countries with abundant fiscal resources to provide for millions of additional residents. Colombia's GDP per capita is $6,600. Peru's is $7,100. They face the same fiscal constraints as other middle-income developing countries: inadequate tax bases, competing demands for infrastructure investment, and pressure to maintain social spending for their own citizens. Adding millions of refugees strains systems already operating near capacity.

The direct fiscal costs are substantial. Education for refugee children requires building new schools, training additional teachers, and providing materials in a context where domestic students often lack adequate resources. Colombia's education system serves approximately 10 million students. Adding 600,000 Venezuelan children (a rough estimate based on the demographic composition of refugee flows) represents a 6% increase in the student population, with no corresponding increase in tax revenue, since most refugee families work in the informal sector.

Healthcare costs compound the pressure. Venezuela's healthcare system's collapse means many refugees arrive with untreated chronic conditions, delayed vaccinations, and mental health impacts from displacement trauma. Colombian public hospitals must provide emergency treatment regardless of immigration status. The costs appear in hospital budgets as bad debt. The Ministry of Health lacks the resources to fully reimburse facilities. The burden falls on regional governments operating on tight margins.

Infrastructure strain shows up in housing, water, sanitation, and transportation. Colombian border cities like Cúcuta absorbed population increases of 20-30% within a few years. The housing stock cannot expand that quickly. Informal settlements proliferate. Water treatment plants designed for 600,000 people must serve 750,000. Public buses run overcrowded. Traffic congestion worsens. These are not minor inconveniences. They represent a declining quality of life for both refugees and host communities, breeding resentment that politicians can exploit.

The labour market impacts are complex. On one hand, Venezuelan workers fill gaps in sectors Colombians avoid: domestic service, agriculture, construction, and street vending. This provides cheap labour, benefiting some businesses. On the other hand, the influx depresses wages in informal sectors where both Venezuelans and working-class Colombians compete for jobs. A Colombian construction worker who earned $15 daily before the refugee influx now faces competition from Venezuelans willing to work for $10. The economic literature on the impacts of refugee labour markets shows heterogeneous effects, but the distributional consequences consistently harm the poorest citizens of host countries.

Peru faces similar dynamics. Lima's informal sector absorbed hundreds of thousands of Venezuelan workers, expanding the pool of street vendors, delivery drivers, and service workers. This intensified competition for positions that were already precarious. Peruvian workers displaced from informal sector jobs have few alternatives. The formal sector requires credentials and connections that most lack. The result is downward pressure on wages and working conditions for the most vulnerable workers in both populations.

The regional fiscal burden can be roughly estimated. Colombia's government estimates the cost of Venezuelan migration at approximately $3 billion annually, covering education, healthcare, and security. This represents about 1% of GDP or roughly 4% of the national government budget. For a country already running fiscal deficits and struggling to fund infrastructure, this is not trivial. Peru's estimate is $1.5 billion annually. Ecuador's is $600 million. The cumulative regional cost exceeds $6 billion per year, with costs concentrated in countries least equipped to bear them.

The development economics literature on forced displacement shows these costs compound over time. Initially, refugees draw down savings and survive on remittances. As time passes and return becomes unlikely, they require integration into permanent housing, education systems, and labor markets. This requires investment that producing temporary shelter and emergency food distribution does not. Colombia and Peru must either spend resources integrating millions of Venezuelans or accept the emergence of permanent underclasses with no legal status, limited education, and no path to formal employment.

The United States, having intervened to capture Maduro and claiming to be restructuring Venezuela's government, bears none of these costs directly. American taxpayers do not fund schools for Venezuelan refugee children in Colombia. American hospitals do not treat Venezuelan refugees. American cities do not face infrastructure strain from population surges. The costs are externalised to countries that neither created the crisis nor possess the resources to address it adequately.

This is the pattern imperial economics produces. The powerful country makes geopolitical decisions based on its strategic interests. The spillover costs fall on weaker countries with no voice in the decision. When regional costs become unsustainable, the powerful country will point to the resulting instability as evidence that weaker countries cannot govern themselves and thus require further intervention. The cycle repeats.

Greenland: NATO ally becomes acquisition target

On 22 December 2025, Trump posted on Truth Social: "For purposes of National Security and Freedom throughout the World, the United States of America feels that the ownership and control of Greenland is an absolute necessity." He refused to rule out military force.

Greenland is not unclaimed territory. It is an autonomous constituent country within the Kingdom of Denmark. Denmark is a NATO ally, a founding member of the European Community, and a signatory to dozens of treaties with the United States. None of this mattered.

The Greenland crisis escalated through January. Trump threatened 25% tariffs on European goods if Denmark did not "immediately" enter negotiations on Greenland's sale. Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen stated the obvious: "Greenland is not for sale and will never be for sale." Greenland's Premier Múte Egede was more direct: "We are not for sale and will not be for sale. Our future is for us to decide."

At Davos on January 21, Trump reversed position, pledging not to use military force but insisting on "immediate negotiations" over Greenland's future. NATO officials claimed agreement on a "framework" for Arctic cooperation. But the damage was done: a NATO ally had been publicly threatened with economic coercion and military force over territorial annexation.

The implications extend beyond Greenland. If the United States can threaten to seize territory from a NATO ally using tariffs and military force, what constraint remains on its behaviour toward non-allied developing countries? The answer Trump himself provided: "My own morality."

Cuba: Secondary sanctions as an economic weapon

The 29 January executive order on Cuba represents a different mechanism of coercion. Rather than direct military force, it threatens tariffs on any country that sells oil to Cuba. This weaponises access to American markets to control third countries' trade relationships.

Cuba's dependence on Venezuelan oil had been near total. Venezuela supplied approximately 55,000 barrels per day under concessional terms, allowing Cuba to maintain a basic energy supply. With Venezuela now under US administration, that supply has stopped. Cuba faces an energy infrastructure collapse, with blackouts lasting up to 20 hours a day in some regions.

The humanitarian consequences follow predictable chains. Cuba's infant mortality rate, which reached a low of 4.7 per 1,000 live births in 2013, rose to 7.1 per 1,000 in 2024. This is not random deterioration. It reflects specific causal mechanisms linking sanctions to child deaths.

First, medication imports. Cuba manufactures some pharmaceuticals domestically but depends on imports for specialised medicines, particularly neonatal care drugs. Antibiotics for treating newborn infections. Surfactants for premature infants with respiratory distress. Insulin for diabetic mothers whose babies face elevated risks. These medications require hard currency to purchase. With oil sales cut off and tourism limited, Cuba lacks foreign exchange. The secondary sanctions threaten any country selling to Cuba with tariffs on its US-bound exports. Suppliers choose the larger market. Medications don't arrive. Babies die from treatable conditions.

Second, electricity-dependent healthcare infrastructure. Modern hospitals require reliable power to maintain incubators for premature infants at precise temperatures. For refrigeration of vaccines and blood products. For operating rooms conducting emergency cesarean sections. For dialysis machines treating maternal kidney failure during pregnancy. The 20-hour blackouts force doctors to choose which patients receive the limited generator capacity. A premature infant in an incubator that loses power for six hours faces a dramatically elevated mortality risk. The medical staff know exactly what choices the power cuts force on them. This is not a natural disaster. It is a policy outcome.

Third, the breakdown of preventive public health infrastructure. Cuba's historically low infant mortality depended on comprehensive prenatal care, mosquito control preventing dengue and Zika in pregnant women, clean water preventing maternal infections, and nutritional support for low-income mothers. All require resources that the sanctions restrict. Pesticides for vector control require imports. Water treatment chemicals require hard currency. Prenatal vitamins require pharmaceutical supply chains. The system deteriorates in ways that become visible only in aggregate statistics months or years later, when the damage is already done.

The emigration data compounds the healthcare crisis. Approximately 12% of Cuba's population has fled since 2021, with medical professionals overrepresented. The best-trained doctors and nurses can earn vastly more in the United States, Mexico, or Spain than in Cuba. The brain drain started before the recent sanctions escalation but has accelerated. Cuba now faces both resource shortages and human capital flight. Hospitals lack both medicines and the staff who would know how to use them.

The economic siege operates through mechanisms designed to inflict maximum civilian cost while maintaining plausible deniability. The United States does not bomb Cuban hospitals. It simply makes the inputs required for hospital operations unavailable. Then it categorizes the resulting deaths as "economic mismanagement" rather than sanctions effects. The causal chain is long enough to obscure responsibility but direct enough that the architects understand exactly what they are doing.

The broader development economics literature on the effectiveness of sanctions shows consistent patterns. Comprehensive economic sanctions almost never compel regime change but reliably increase child mortality, particularly among populations under five. Iraq, under the 1990s sanctions, saw infant mortality double. The mechanisms are identical: restricted medication imports, degraded infrastructure, medical personnel flight, and deteriorated public health systems. The stated goal (regime change) fails. The predictable cost (increased child deaths) occurs. Policymakers claim surprise.

The secondary sanctions mechanism operates through threat. Any country that sells oil to Cuba risks tariffs on its exports to the United States. For most oil-producing countries, the American market is far more valuable than sales to Cuba. The rational economic choice is to comply. Cuba is isolated not by direct prohibition but by making the price of helping it unbearably high.

The legal basis offered is "national security." The Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, originally enacted to restrict commerce with Germany during World War I, has been continuously renewed to apply to Cuba since 1962. Cuba was re-listed as a state sponsor of terrorism in the final days of Trump's first term, a designation lifted by Biden and restored by Trump in January 2026.

The Article XXI "security exception" in GATT allows countries to take necessary actions to protect essential security interests. The WTO's first ruling on this provision, in the Russia-Transit case (2019), confirmed that security invocations are subject to review rather than purely self-judging. But with the Appellate Body dead, who reviews?

The Cuba policy demonstrates power unconstrained by legal process. The United States designates countries as security threats, imposes sanctions, and threatens third parties who do not comply. No multilateral review. No dispute panel. No appeals. Just consequences for non-compliance.

India in the crosshairs: Sectoral vulnerability and compounding dependencies

India's position in this emerging order reveals how quickly decades of trade integration can become an economic liability. The United States accounts for 18% of India's merchandise exports, making it India's largest single export market. Trump has threatened 26% reciprocal tariffs on Indian goods, citing India's own tariff structure. India's trade surplus with the United States stood at $31 billion in 2024.

The immediate sectoral impacts would concentrate in three areas. First, pharmaceuticals and medical devices. India supplies approximately 40% of generic drugs consumed in the United States, with exports totalling $9.2 billion in 2024. These generics provide affordable treatment for millions of Americans while employing hundreds of thousands of Indian workers in manufacturing clusters around Hyderabad and Ahmedabad.

A 26% tariff would price many Indian generics out of the market relative to domestic American production or European competitors. The pharmaceutical sector employs approximately 3 million people in India when supply chain workers are included. The ripple effects would devastate cities like Hyderabad where entire economies revolve around pharma clusters.

Second, textiles and apparel. India exported $4.2 billion in textiles and clothing to the United States in 2024. The sector is labor-intensive, employing approximately 45 million workers nationally, with export-oriented firms paying significantly better wages than domestic-market producers. Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, and Maharashtra host the major clusters. These are not workers with abundant alternative opportunities. They are predominantly women from rural backgrounds who migrated to textile cities precisely because factory work offered escape from agricultural subsistence or domestic service. Destroying their export markets pushes them back into sectors with lower pay, worse conditions, and fewer advancement opportunities.

Third, engineering goods and auto components. India's engineering exports to the United States reached $19.2 billion in 2024-25, including automotive parts, machinery, electrical equipment, and precision instruments. These sectors employ skilled workers and technicians, precisely the middle-skill jobs that developing economies need to escape the middle-income trap. Tamil Nadu's auto component cluster supplies global manufacturers. Suppliers cannot simply redirect to other markets because American automakers specify components designed to American standards. Losing US market access means closing facilities and laying off workers who spent years developing specialised skills.

The state-level exposure concentrates the political economy. Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Karnataka, and Telangana account for approximately 65% of India's US-bound exports. These are also the states driving India's economic growth. Maharashtra's GDP per capita is nearly double the national average. Tamil Nadu's industrial employment sustains millions of families. Tariffs that devastate these states' export sectors would both slow national growth and create regional political crises.

The compounding vulnerability comes from India's energy dependency on Russian oil. India imports approximately 35% of its oil from Russia, with purchases increasing dramatically after the war in Ukraine began. This occurred partly because Russian oil was sold at discounts after Western sanctions, allowing India to reduce its import bill amid high global energy prices. But it created strategic exposure. Trump's transactional approach to sanctions creates leverage: the United States could threaten secondary sanctions on Russian oil buyers, forcing India to choose between energy security and market access.

This is not hypothetical. The 29 January executive order threatening tariffs on any country selling oil to Cuba establishes the mechanism. If Trump can threaten tariffs on Cuba's oil suppliers, he can threaten the same against Russia's oil buyers. India's energy imports from Russia totalled approximately $34 billion in 2024. Replacing that volume at current global prices while also absorbing tariff costs on US-bound exports would create a fiscal crisis. India's current account deficit, already running at 1.2% of GDP, would widen dramatically. The rupee would face depreciation pressure. Import-dependent sectors would see input costs spike. The economic impact would cascade through the domestic economy far beyond the direct export losses.

The structural problem is that India cannot access the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration arrangement for disputes with non-participating countries. The MPIA functions only between members. The United States refuses Appellate Body jurisdiction. If the United States imposes tariffs on India and India challenges at the WTO, the dispute would reach a panel. The panel would likely rule for India based on established WTO jurisprudence that reciprocal tariffs violate Article I GATT. But then what? With no functioning Appellate Body and the United States refusing MPIA arbitration with India, there is no binding review. The United States could simply ignore the panel ruling, as it has done in previous disputes. India would win the legal case and lose the economic war.

The IMF has already downgraded India's growth forecast for FY26 from 6.5% to 6.2%, citing "uncertainty from shifting US trade policy." This is diplomatic language for "American trade threats are dampening investment." When firms cannot predict whether their export markets will remain accessible, they delay expansion plans. Workers don't get hired. Equipment doesn't get purchased. The growth that would have employed millions of people in productive jobs simply doesn't happen.

India's bilateral trade talks with the United States, announced at Davos with the "terms of reference" being finalised, are taking place under this shadow. Vice President J.D. Vance announced the framework. But negotiating under coercion is not the same as negotiating under rules. The power dynamic is visible in every concession. India might win some sectoral protections by offering geopolitical cooperation on China containment. But this converts trade policy into a strategic bargaining chip rather than an economic relationship governed by neutral rules.

The alternative paths are limited. South-South trade networks could absorb some displaced exports, but India's major developing-country trade partners (ASEAN, Africa) lack the market size to replace US demand. The European Union could expand, but faces its own protectionist pressures. China would be willing but accepting dependence on China to escape dependence on America creates new vulnerabilities. Regional trade agreements like RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) offer modest buffers but cannot substitute for access to the world's largest consumer market.

India knows this history. The East India Company arrived as traders before becoming rulers. The company leveraged trade relationships to secure political concessions, then used political power to expand its trade dominance. Eventually, the distinction between commerce and sovereignty disappeared. India spent nearly two centuries fighting to restore that distinction. The WTO represented a formal acknowledgement that India's trade interests would be treated as legally cognizable, not subject to arbitrary power. The emerging system offers no such guarantee. It treats market access as a political favour to be granted or withdrawn based on geopolitical compliance.

The question facing India is what Bangladesh, Vietnam, Mexico, and dozens of other developing countries also face: whether to accept bilateral deals negotiated under duress, attempt to build alternative trade networks among developing countries, or risk economic isolation from the markets that drove their development over the past three decades. None of these options is attractive. All of them are worse than the rules-based system that functioned, imperfectly, for seven decades.

The Monroe Doctrine returns

The "Trump Corollary" to the Monroe Doctrine, issued 2 December 2025, formally asserts that "the American people, not foreign nations nor globalist institutions, will always control their own destiny in our hemisphere."

This is not new rhetoric dressed in modern language. It is old rhetoric revived without disguise. The Monroe Doctrine of 1823 declared the Western Hemisphere closed to European colonisation. The Roosevelt Corollary of 1904 asserted American rights to intervene in Latin American countries deemed to be experiencing "chronic wrongdoing." The result was decades of interventions: Nicaragua, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Cuba, Chile, Grenada, Panama.

The post-World War II order was supposed to replace this with multilateral institutions and agreed-upon rules. The Organisation of American States, established in 1948, embodied the principle of non-intervention. The WTO, established in 1995, embodied the principle of non-discrimination. Both are now treated as optional.

Chatham House warns: "The system that prevailed before the recent shocks is gone forever." The question is what replaces it.

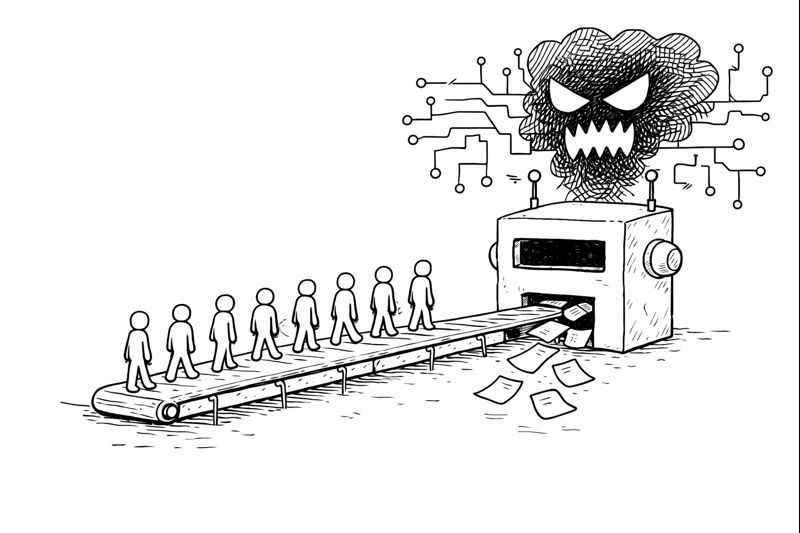

What comes after rules? The economics of regression

The rules-based international economic order is not dying of natural causes. It is being actively dismantled by its principal architect. The system that GATT's framers designed specifically to prevent another Smoot-Hawley catastrophe, to replace power politics with law, discrimination with non-discrimination, unilateralism with multilateral adjudication, now faces explicit rejection by the power whose postwar hegemony made the system possible.

The EU's Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration offers a partial workaround for willing participants. Regional arrangements may proliferate. The UNCTAD reports that South-South merchandise exports rose from $0.5 trillion in 1995 to $6.8 trillion in 2025, with 57 per cent of developing-country exports now going to other developing markets. Deeper regional integration may buffer some countries from American coercion. But these are patches on a system losing its foundation.

Development economists have long debated whether trade liberalisation helps or harms the poor. The evidence is mixed, contingent on domestic institutions, industrial policy, and social protection. But that debate assumed a world where trade rules exist and are enforced. What happens when rules disappear?

The historical precedent is not encouraging. The interwar period's bilateral trade deals and competitive devaluations did not produce shared prosperity. They produced beggar-thy-neighbour policies, economic nationalism, and ultimately war. The GATT system emerged specifically to prevent repetition. Trump's explicit statement that he does not need international law takes us back to a world where might makes right.

Without rules, trade will concentrate among countries with market size or strategic importance. Small, poor countries will be excluded from the growth opportunities that lifted billions from poverty. This is not speculation about distant futures. It is happening now. The Yale Budget Lab's analysis of Trump's proposed tariffs estimates that effective tariff rates on imports could reach 28%, the highest since the 1940s. This is not negotiating leverage. It is the reconstruction of walls that took 80 years to dismantle.

The economic forecast is straightforward. Countries currently dependent on US market access face three options, none attractive. First, accept bilateral deals negotiated under coercion, trading policy sovereignty for market access on terms that can shift with each political wind. Second, attempt to build alternative trade networks among developing countries, recognising that South-South trade cannot fully replace North-South flows given existing consumption patterns and income levels. Third, face economic isolation from markets that drove their development over the past decades.

For India specifically, the implications are stark. The country pursued trade liberalisation in 1991 on the assumption that multilateral rules would prevent discriminatory treatment. The WTO accession in 1995 embodied that bargain. Now the hegemon that wrote those rules announces it no longer needs them. India can submit to American terms, intensify regional integration through frameworks like RCEP that exclude the United States, or accept slower growth while diversifying trade relationships. Each path involves costs. The difference from the pre-1991 era is that India now has productive capacity oriented toward exports that might not find markets.

Bangladesh faces even starker choices. The garment sector that transformed the economy depends on reliable market access. If US buyers cannot be confident that their Bangladeshi suppliers' products will clear customs at predictable tariff rates, the orders go elsewhere. Bangladesh cannot simply pivot to China or India as buyers because those markets don't absorb comparable volumes of garments. The workers return to agriculture or informal services at a fraction of their previous wages. Decades of development gains reverse within years.

The broader pattern holds for most low and middle-income countries. Vietnam, Mexico, Thailand, Morocco, Tunisia, and dozens more pursued export-led growth under the assumption that WTO rules protected market access. When rules disappear, those countries must either accept political subordination or accept economic marginalisation. The development model that worked for the past 70 years no longer functions.

The alternative systems developing countries might face serious limitations. South-South trade networks can expand, and the growth from $0.5 trillion to $6.8 trillion over 30 years suggests potential. But most developing countries still rely on rich-country markets for manufacturing exports because those markets have the highest purchasing power. Regional arrangements like the African Continental Free Trade Area face problems of overlapping memberships, inadequate infrastructure for intra-regional trade, and limited complementarity in production structures.

The political economy of transition is even more fraught. Export-oriented manufacturing created politically influential constituencies supporting open trade. These constituencies lose power and resources as exports decline. Protectionist coalitions gain strength. The temptation to respond to American protectionism with retaliatory protection grows, even though tit-for-tat trade wars harm all participants. The nationalist rhetoric that justified dismantling the rules-based order in the United States finds echoes in other countries facing similar distributional conflicts.

India knows this history better than most. The East India Company arrived as traders seeking commercial opportunity. They negotiated trade concessions from Mughal authorities. They used those concessions to build political power. Eventually the company ruled half the subcontinent. The formal British Empire that followed lasted until 1947. The entire experience taught that allowing commerce to become vehicle for political subordination eventually destroys both sovereignty and prosperity.

The WTO, for all its flaws, treated India's trade interests as legally cognizable. When India had disputes with the United States over poultry, solar panels, or steel, both countries argued before neutral panels applying agreed-upon rules. India won some cases and lost others based on legal merit rather than power disparities. The system was imperfect, often favoured developed countries in rule-making, and failed to address many developing countries' concerns. But it was law, not force.

The emerging system offers no such constraints. Market access becomes political favour granted or withdrawn based on geopolitical compliance. Trade negotiations occur under duress. Disputes are resolved through power rather than legal process. This is not a new world order. It is the old imperial system that the GATT was created to replace.

My son will inherit whatever comes next. I hope it involves rules. The alternative we tried before. The Smoot-Hawley tariffs of 1930 triggered retaliation from trading partners. Global trade collapsed by two-thirds. The resulting economic devastation fed the political extremism that produced World War II. The generation that survived that catastrophe built institutions specifically designed to prevent repetition. Those institutions are being deliberately destroyed by leaders who either do not know this history or believe it no longer applies to them.

The economics are clear. Rules-based trade enabled the greatest poverty reduction in human history. The system was imperfect and heavily influenced by powerful countries. But it established the principle that small countries could trade with large ones on legally enforceable terms. When those terms disappear, so do the development opportunities they enabled. This is not abstract theory. It is the difference between futures in which Bangladesh continues its convergence toward middle-income status and futures in which garment workers return to subsistence agriculture. Between futures where India sustains 6% annual growth, or futures where growth slows to 3-4% as export sectors collapse. Between futures where developing countries have options, or futures where survival requires submission.

My son asked me last week why countries follow rules. I told him about Bretton Woods, the GATT, and the WTO. I explained how the powerful's self-binding made cooperation possible. How smaller countries could trade with larger ones, knowing disputes would be settled by law, not by gunboats.

He asked if this was still true. I did not know how to answer. I still don't. But I know the question matters more than ever.

Varna is a development economist and writes at policygrounds.press.

Further Reading

WTO Dispute Settlement Crisis, International Institute for Sustainable Development

The WTO's First Ruling on National Security, Center for Strategic and International Studies

US Actions in Venezuela Violated International Law, The Conversation

WOLA Statement on Venezuela Intervention, Washington Office on Latin America

Greenland Crisis Timeline, Wikipedia

Cuba's Energy Crisis: A Systemic Breakdown, IEEE Spectrum

Cuba's Quest for Oil After Venezuela, Cuba Headlines

Cuba Redesignated as State Sponsor of Terrorism, US State Department

Trump Threatens 26% Tariff on India, Economic Times

India-US Bilateral Trade Talks Begin, Business Standard

President Trump May Disregard International Law, Chatham House

The Return of Imperial Economics, Irish Times

Write a comment ...