The VB-G RAM G Bill doesn't reform MGNREGA—it guts it fiscally, institutionally, and morally. "125 days" is the headline. The fine print is a ₹55,000 crore heist.

I have written before about the jobless recovery that India's official statistics claim we are experiencing—unemployment down, labour force participation up, women flooding into the workforce. And I have explained why those numbers are a mirage: the "jobs" being counted are overwhelmingly self-employment, much of it unpaid family work, much of it distress-driven. When the formal economy fails to generate decent employment, people don't sit idle. They scramble. They take whatever job they can find. They show up in the statistics as "employed."

MGNREGA was supposed to be the floor beneath which rural India could not fall. Not a solution to unemployment—no programme can be that—but a guarantee that if everything else failed, if the rains didn't come, if the harvest was poor, if the factory closed, if the contractor didn't pay, you could at least demand 100 days of work from the state at a known wage. It was a right, justiciable, backed by law.

Today, that right is being repealed.

What the Bill Actually Does

On 15 December 2025, Rural Development Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan introduced the Viksit Bharat—Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) Bill, 2025—mercifully abbreviated to VB-G RAM G—in the Lok Sabha. The Bill proposes to repeal the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act of 2005 in its entirety and replace it with a new framework "aligned with the national vision of Viksit Bharat 2047."

The headline: guaranteed employment days increase from 100 to 125.

The fine print: everything else gets worse.

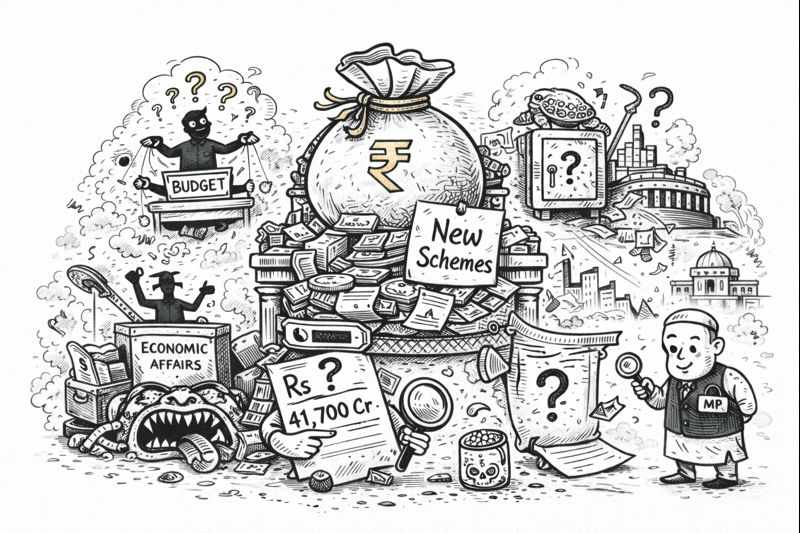

1. The Fiscal Bombshell: 60:40 Cost-Sharing

This is the most consequential change, and it has received the least attention.

Under MGNREGA's current funding pattern, the Central government bears 100% of wage costs for unskilled manual work and 75% of material costs. States contribute only the remaining 25% of materials. The scheme is, effectively, a Central Sector programme—the Union bears the fiscal responsibility, as it should for a national employment guarantee.

The VB-G RAM G Bill converts this to a Centrally Sponsored Scheme with a 60:40 Centre-State funding pattern for most states. Only Northeastern states, Himalayan states (Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh), and Jammu & Kashmir retain the 90:10 ratio.

What does this mean in practice?

If the legislation is implemented nationwide, the total estimated annual requirement is ₹1,51,282 crore. The Central share would be ₹95,692 crore. States would collectively bear approximately ₹55,590 crore annually—money they currently do not spend on the scheme.

"Today, total expenditure of MGNREGA in a state like Rajasthan is around ₹10,000 crore per annum," Nikhil Dey of MKSS told Business Standard. "The big question is, with the changed funding pattern, will states bear 40 per cent of this expenditure?"

The answer, of course, is that many states cannot. Kerala—a state that has used MGNREGA effectively—would face an additional burden of ₹2,000-2,500 crore. For fiscally stressed states like West Bengal, Jharkhand, or Chhattisgarh, the numbers are equally daunting.

This is cost-shifting by stealth, not reform. The Centre walks away from its fiscal obligations while claiming credit for "increasing" the number of employment days.

2. From Demand-Driven Rights to Normative Allocation Ceilings

This is the architectural shift that transforms the guarantee's character.

Under MGNREGA, the system is demand-driven. A worker demands work → the state provides it → the Centre pays for it. The funding is open-ended because the entitlement is open-ended. If more people need work, more funds flow.

The VB-G RAM G Bill introduces "normative allocation":

"The Central Government shall determine the State-wise normative allocation for each financial year, based on objective parameters as may be prescribed by the Central Government."

This is fundamentally different. The Centre now allocates a fixed amount to each state based on parameters it chooses. When that allocation exhausts, the state must either fund additional work from its own budget or turn workers away.

The implications are profound:

Under MGNREGA: Worker demands work → State provides → Centre pays (demand-driven, rights-based)

Under VB-G RAM G: Centre allocates a fixed amount → When funds are exhausted, entitlement ends (supply-constrained, allocation-based)

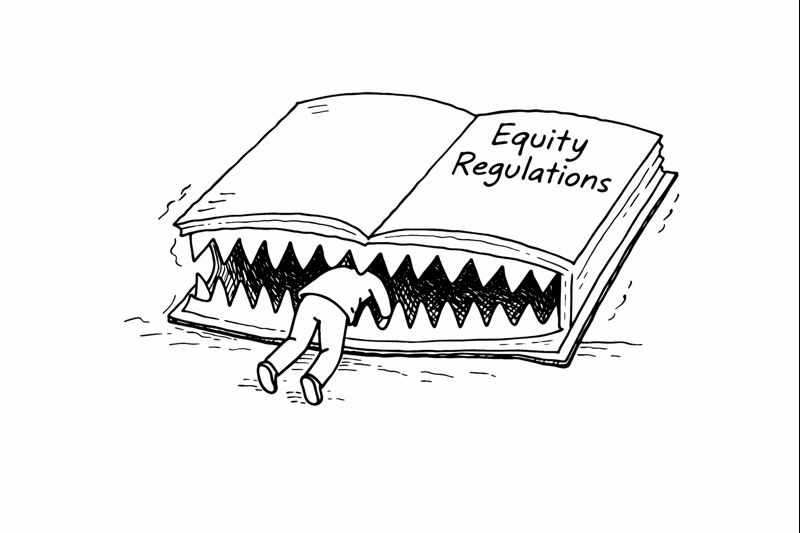

A legal employment guarantee becomes a centrally managed budget line. Rights become ceilings.

3. The 60-Day Suspension: State-Managed Labour Supply

This provision has received attention, but its implications deserve deeper scrutiny.

Section 6(1) of the Bill states:

"Notwithstanding anything contained in this Act or rules made thereunder, and to facilitate adequate availability of agricultural labour during peak agricultural seasons, no work shall be commenced or executed under this Act, during such peak seasons as may be notified."

States can suspend the scheme for up to 60 days during "peak agricultural seasons."

Think about what this means. The employment guarantee exists precisely when people need work most, often when private agricultural employment is uncertain or poorly paid. Stopping public works to "facilitate adequate availability of agricultural labour" means forcing MGNREGA workers to take whatever wages private farmers offer.

This is not welfare. This is state-managed labour supply, stripping workers of wages, choice, and dignity.

As CPI(M) MP John Brittas put it: "Employment guarantee or labour control? Scheme labourers are legally told: Don't work. Don't earn. Wait."

4. Panchayats Sidelined, Dashboards Empowered

MGNREGA was designed around decentralised planning. Gram Sabhas identified works based on local needs. Panchayats planned and executed. The scheme trusted local institutions.

The VB-G RAM G Bill mandates integration with centralised digital infrastructure:

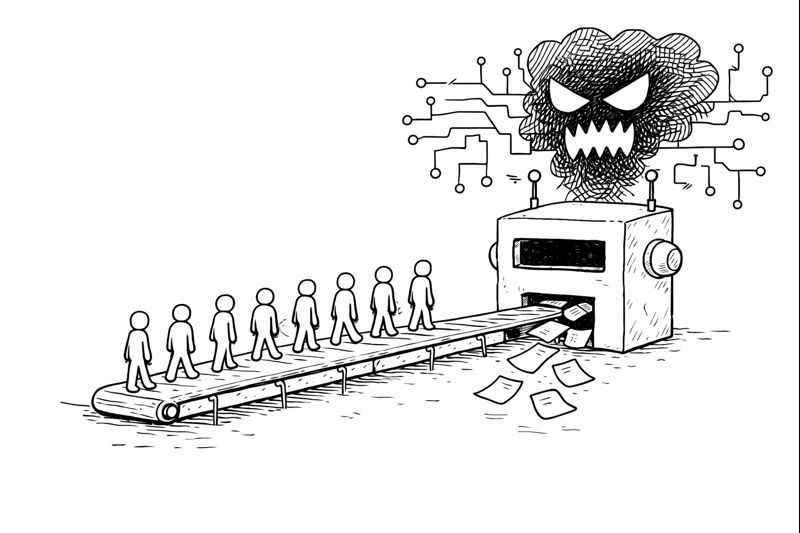

"A comprehensive digital ecosystem, including biometric authentication at various levels, global positioning system or mobile-based worksite monitoring, real-time management information system dashboards, proactive public disclosures, and use of artificial intelligence for planning, audits and fraud risk mitigation, will be used to modernise governance, accountability and citizen engagement."

The Bill integrates "Viksit Gram Panchayat Plans" with PM Gati Shakti—the Centre's infrastructure layer. Local priorities must now pass through a "Viksit Bharat National Rural Infrastructure Stack."

I have written before about data obfuscation as Modi operandi. This is its operational cousin: techno-administrative capture. Biometrics, geo-tagging, dashboards, and AI audits become statutory requirements. For millions of rural workers—many of whom are elderly, many of whom have worn fingerprints from manual labour, many of whom live in areas with poor connectivity—tech failures will mean exclusion without appeal.

"Finger nahi kaam kiya"—the finger didn't work—is already shorthand among MGNREGA workers for the biometric authentication failures that deny them their entitled wages. The new Bill makes this system mandatory and statutory.

5. What Else Gets Diluted

The Business Standard analysis notes additional concerns:

Contractor prohibition diluted: MGNREGA banned contractors to prevent exploitation and ensure that wages went directly to workers. The new Bill reportedly dilutes this prohibition.

5-kilometre guarantee weakened: MGNREGA guaranteed work within 5 km of the worker's residence; if work was further away, additional wages were mandated. Critics say this provision is diluted.

Unemployment allowance shifted to states: Under MGNREGA, if work is not provided within 15 days, the state must pay an unemployment allowance, with the Centre sharing the burden. Under the new Bill, this becomes entirely the state's responsibility.

What the Parliamentary Standing Committee Actually Recommended

Here's the bitter irony. Just two days before the Bill was introduced, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Rural Development and Panchayati Raj—chaired by Congress MP Saptagiri Sankar Ulaka—tabled a report in the Lok Sabha.

What did Parliament's own committee recommend?

Increase employment days to 150, not 125

Raise wages to at least ₹400 per day (current wages range from ₹241 to ₹400 across states)

Link wages to an inflation index rather than the outdated CPI-AL

Conduct an independent survey to assess the scheme's effectiveness

Fix the National Mobile Monitoring System before making it mandatory

The committee specifically flagged that MGNREGA wages "remain below subsistence levels" and questioned why the Ministry continued to send "stereotype responses" about wage revision.

The government's response to a parliamentary committee recommending 150 days and ₹400 wages was to introduce a Bill offering 125 days, no wage increase, and ₹55,000 crore in additional costs to be shifted to the states.

The Political Economy of This "Reform"

Why is this happening? Why now?

First, the fiscal context. The Centre has been chronically underfunding MGNREGA for years. Budget allocations have not kept pace with demand; states routinely face fund shortages; wage payments are delayed for months. By converting the scheme to a Centrally Sponsored Scheme with fixed allocations and state cost-sharing, the Centre caps its own liability while offloading the burden.

Second, the federalism angle. This continues a pattern visible across recent legislation: increasing central control while shifting fiscal burden to states. The Fifteenth Finance Commission's horizontal devolution formula already disadvantaged states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu. The VB-G RAM G Bill compounds this by:

Using "normative allocation based on objective parameters" (likely poverty indices) that would further reduce allocations to better-performing states

Making states bear 40% of costs while the Centre determines where and how the scheme operates

Giving the Centre the power to freeze fund releases

Third, the ideological project. The name change is not incidental. Removing "Mahatma Gandhi" from India's most extensive rural employment programme is a deliberate political statement. The scheme was a UPA flagship; it must be rebranded as a BJP achievement. Prime Minister Modi famously called MGNREGA a "living monument to the failures of Congress" in 2015. Ten years later, the monument is being demolished.

The Poverty Claim That Justifies Everything

The Bill's Statement of Objects and Reasons rests on a remarkable claim: that poverty in India has declined from 25.7% in 2011-12 to 4.86% in 2023-24.

I have written about India's measurement problems before. This poverty figure deserves similar scrutiny.

The 4.86% figure comes from NITI Aayog's Multidimensional Poverty Index, which uses a methodology different from consumption-based poverty measurement. Alternative estimates—including from the World Bank and independent researchers using consumption survey data—put poverty rates substantially higher, in the range of 12-15% for extreme poverty and 26-27% for the broader poor.

More importantly, even if poverty has declined, does that mean the employment guarantee is no longer needed? The demand for MGNREGA work has not decreased. In 2023-24, over six crore households demanded work. The average employment provided was around 50 days per household, half the guarantee. Pending wage payments run into thousands of crores.

The scheme remains in demand because the alternative—dependable, decent private employment at living wages—does not exist. That was the argument I made about India's jobless recovery, and nothing in this Bill changes that reality.

What This Means

Let me be precise about what the VB-G RAM G Bill does:

Shifts ₹55,000+ crore annually from the Centre to states while claiming to "enhance" the scheme

Converts a demand-driven right to a supply-constrained allocation, capping entitlements

Mandates a 60-day work suspension to ensure labour availability for private agriculture

Centralises planning through digital stacks, replacing local Panchayat autonomy

Makes biometric authentication and tech compliance statutory, creating new exclusion mechanisms

Dilutes contractor prohibitions and distance guarantees that protect workers

It does all this while increasing guaranteed days from 100 to 125—a headline improvement that obscures structural dismantling.

I wrote in Safety Nets, As If People Matter that India's welfare architecture suffers from a fundamental confusion about whether poor people are citizens with rights or beneficiaries of charity. MGNREGA, for all its implementation failures, was designed as a right. You could demand work. The state had to provide it. The entitlement was yours.

The VB-G RAM G Bill converts that right back into a scheme—a programme the government administers, allocates, suspends, and controls. Same workers. Fewer rights. More burden.

This is not reform. This is demolition dressed as renovation.

NREGA Sangharsh, a rights group representing MGNREGA workers, demanded on Monday that any changes to the Act should come only after "public disclosure and democratic consultations" with labourers, workers' organisations, trade unions and the states. "We will oppose and resist this regressive step," NREGA Sangharsh said. "We will not allow the law, made from the struggles of workers, to be ended by unilateral decisions."

Further reading:

Parliamentary Standing Committee Report on MGNREGA (December 2024)

Centre proposes renaming MGNREGA to VB-RaM G, to change funding pattern - Business Standard

CPI(M) MP John Brittas's critique - The South First

MGNREGA Dashboard - Official data on employment, wages, and expenditure

Write a comment ...